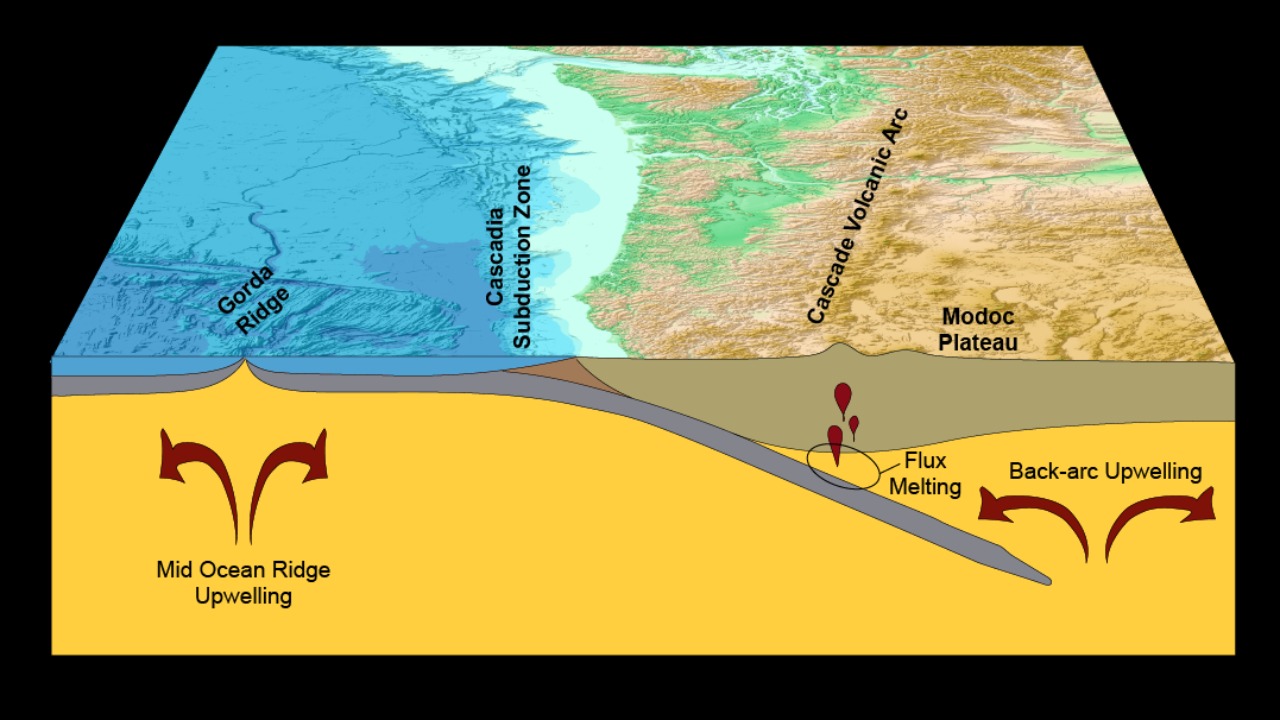

The Cascadia Subduction Zone is quietly loading energy that will one day unleash a megathrust earthquake, and a growing cluster of new measurements suggests that the system is edging closer to failure. From accelerating slow-slip events to rising fluid pressures deep offshore, at least nine distinct red flags now point to a region where tectonic stress is building, not relaxing. I will walk through each signal in turn, drawing on recent seismic, geodetic, and geological reporting that together outline a sobering picture of Cascadia’s evolving risk.

1. Accelerating Slow-Slip Events Near Olympic Peninsula

Accelerating slow-slip events near the Olympic Peninsula are one of the clearest new red flags for a Cascadia megaquake. In a 2023 United States Geological Survey report, slow-slip events along the Cascadia subduction zone were found to have accelerated, with a 15% increase in slip rate detected between 2019 and 2022 near the Olympic Peninsula. That change is not a minor fluctuation in background noise; it is a measurable shift in how the plate interface is releasing strain. Slow-slip events, which unfold over days to weeks rather than seconds, still represent real fault movement, and a sustained 15% increase in slip rate suggests that the deeper part of the megathrust is behaving differently than it did just a few years ago.

Researchers have also highlighted how slow slip can be influenced by other earthquakes in the region. A recent study reported that a 2022 earthquake in Northern California may have triggered slow slip in the Cascadia Subduction Zone, underscoring how sensitive this plate boundary is to stress perturbations along its length. That finding, detailed in work on how earthquakes can trigger megathrust slip, reinforces the idea that Cascadia’s slow-slip behavior is part of a larger, interconnected stress system. For communities from the Olympic Peninsula to Vancouver Island, an uptick in slow-slip rates is not reassuring; it indicates that the fault is actively evolving, and that deeper segments may be inching toward conditions that could eventually cascade into a full-margin rupture.

2. Locked Plate Convergence Measured by GPS

Locked plate convergence measured by GPS provides a second, equally stark warning sign. GPS data from the Plate Boundary Observatory, analyzed in a 2022 study in Geophysical Research Letters, shows 2–3 cm per year of locked plate convergence building strain from northern California to British Columbia. That rate of convergence means the overriding North American Plate and the subducting oceanic plate are effectively welded together over large stretches of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, accumulating elastic energy that can only be released through slip on the fault. Over decades, 2–3 cm per year translates into tens of centimeters of stored offset, and over centuries it becomes meters of potential rupture.

Other geodetic work has emphasized that The Cascadia undergoes 25–40 mm per year of convergent relative plate motion, with some of the slip budget being released in Episodic Tremor and Slip, and with individual slow-slip episodes capable of accommodating up to 40 m of motion at depth. That broader context, described in subdaily GPS imaging of slow slip events at The Cascadia, highlights how much of the plate motion is still being locked rather than sliding smoothly. When GPS stations across northern California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia all register consistent 2–3 cm per year of shortening, it signals that the megathrust is primed. For infrastructure planners, that steady convergence is a quantitative reminder that every year of apparent quiet is actually another year of strain loading that will eventually have to be paid back in seismic shaking.

3. Surge in Deep Tremors During 2023 ETS Event

A surge in deep tremors during the 2023 Episodic Tremor and Slip cycle adds a third red flag to Cascadia’s risk profile. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network recorded 47 deep tremors in the ETS zone during the September 2023 event, which is 20% more than the average of prior cycles. Deep tremors occur in the transition zone between the locked and freely sliding parts of the subduction interface, and they are closely associated with slow-slip episodes. An increase from typical counts to 47 tremors in a single event suggests that the deeper interface is experiencing more frequent or more vigorous episodes of stress release, which can alter how stress is transferred upward toward the locked zone that will host a future megathrust earthquake.

Scientists have framed this behavior within the broader slow slip phenomenon, also known as ETS, which is described as an episode of relative tectonic plate movement accompanied by high frequency seismic tremors. That characterization, laid out in work on the Cascadia slow slip phenomenon, makes clear that tremor counts are not just a curiosity; they are a proxy for how much and how often the plate interface is moving at depth. When the number of deep tremors jumps by 20% above average, it implies that the system is in a more active state, with more energy being shuffled around the deeper parts of the fault. For emergency managers, a more tremor-rich ETS cycle is a reminder that Cascadia’s deep engine is running hot, and that changes in tremor behavior can be an early indicator of evolving conditions on the locked megathrust above.

4. The 1700 Tsunami as a Historical Benchmark

The 1700 tsunami stands as a historical benchmark that anchors modern concerns about a future Cascadia megaquake. Paleoseismic records from coastal marshes, detailed in a 2021 Quaternary Science Reviews paper, indicate that the last full-margin rupture occurred on January 26, 1700, generating a tsunami documented in Japanese records. Those marsh deposits, which include sudden subsidence layers and tsunami sands, line up precisely with written accounts from Japan of an “orphan” tsunami that arrived without a felt local earthquake. Together, the geological and historical evidence confirm that the Cascadia Subduction Zone is capable of a magnitude 9 class event that ruptures nearly its entire length and sends waves across the Pacific.

Recent reassessments of coastal evidence have refined this picture further. A maximum rupture model for the central and southern Cascadia subduction zone, summarized in work on Cascadia, underscores that the 1700 event is not an outlier but a representative example of what the margin can do when the locked zone finally fails. For coastal communities from northern California to Vancouver Island, the 1700 tsunami is not just a historical curiosity; it is a direct analog for the next full-margin rupture. The fact that Japanese observers recorded the tsunami in detail, while Indigenous oral histories along the Pacific Northwest coast describe great shaking and flooding, provides a multi-line record of the hazard. As modern monitoring reveals new red flags, the 1700 benchmark serves as a stark reminder that Cascadia’s quiet centuries are punctuated by rare but devastating megathrust earthquakes.

5. Predicted 4–6 Minutes of Intense Shaking in Portland

Predicted shaking scenarios for Portland translate Cascadia’s tectonic signals into concrete urban risk. A 2024 model in Nature Geoscience predicts that a magnitude 9.0 Cascadia event could produce ground shaking lasting 4–6 minutes, with peak accelerations up to 1.0 g in Portland, Oregon. Shaking of that duration and intensity would be far beyond what the city has experienced in recorded history, and 1.0 g peak acceleration means that, at times, the ground could be accelerating at roughly the same rate as gravity. For older unreinforced masonry buildings, aging bridges, and critical lifelines like fuel terminals along the Willamette River, several minutes of such shaking would pose a severe test of structural resilience.

These modeled outcomes are grounded in the same locked plate convergence and historical rupture patterns described elsewhere in Cascadia research. When a full-margin rupture similar to the January 26, 1700 event is combined with modern estimates of 2–3 cm per year of strain accumulation, the resulting slip distribution naturally leads to long-duration shaking in inland cities like Portland. The 4–6 minute window is particularly important for emergency planning, because it implies that building codes must account not only for peak forces but also for how long structures will be forced to flex and sway. For residents, the prospect of several minutes of intense motion underscores why the new red flags in slow slip, tremor activity, and fluid pressures are not abstract; they are early hints of a future event that could subject Portland to some of the most punishing shaking seen in any modern North American city.

6. Unusual Low-Frequency Rumbles from Fluid Migration

Unusual low-frequency rumbles from fluid migration along the subduction interface add a more subtle but technically significant warning sign. Infrasound monitoring by the University of Washington’s 2023 study detected low-frequency rumbles at 20–30 Hz from the subduction interface, correlating with fluid migration 40 km deep. These signals are distinct from typical earthquake waveforms and suggest that pressurized fluids are moving through fractures and shear zones within the downgoing plate and overlying mantle wedge. Because fluids can weaken rock and promote slip, the detection of 20–30 Hz rumbles tied to fluid movement indicates that parts of the interface are being lubricated in ways that could alter how stress is distributed.

Other work on the role of slow slip events in the Cascadia Subduction Zone has emphasized how variations in fluid pressure and rock properties can control where and how the fault creeps versus locks. In one such analysis, researchers interpolated slip rates along 5 km depth intervals of the Cascadia Subduction Zone interface and then averaged the rates for all intervals to understand how different segments respond to stress and fluids. That approach, detailed in a study of slow slip events, provides a framework for interpreting the new infrasound observations. If 40 km deep fluids are migrating in ways that coincide with zones of changing slip rate, it suggests that the mechanical state of the megathrust is evolving. For hazard analysts, the emergence of 20–30 Hz rumbles as a monitoring tool means that Cascadia’s deep plumbing can now be tracked in near real time, offering another line of evidence that the system is not static but actively reconfiguring under the region’s feet.

7. Rising Microseismicity Near Cape Mendocino

Rising microseismicity near Cape Mendocino, California, marks a seventh red flag along the southern end of the Cascadia system. The 2022 EarthScope Consortium report notes a 10% rise in microseismicity, with magnitudes less than 2.0, along the 1,000 km fault from 2020 to 2023, concentrated near Cape Mendocino. Microseismic events of this size are too small to be felt by people, but they are invaluable for mapping how stress is changing on and around the plate boundary. A 10% increase over a three-year window, focused near a key transition zone between the Cascadia Subduction Zone and the San Andreas system, suggests that this area is experiencing a subtle but real uptick in fault activity.

Seismologists often interpret such swarms as indicators that stress is being redistributed, either through small-scale fault creep, fluid movement, or loading from adjacent locked segments. In the context of Cascadia, where GPS data already show 2–3 cm per year of locked convergence and slow-slip events are accelerating, a rise in microseismicity near Cape Mendocino fits a broader pattern of a margin under increasing strain. For local communities in northern California, including towns that rely on Highway 101 and coastal lifelines, the clustering of microquakes is a reminder that the southern Cascadia segment is not isolated from the rest of the subduction zone. Instead, it is part of a 1,000 km long fault system where changes in one segment can influence stress conditions elsewhere, potentially nudging the entire margin closer to a future megathrust rupture.

8. Elevated Fluid Pressures Off Vancouver Island

Elevated fluid pressures off Vancouver Island provide another deep-crustal signal that Cascadia’s megathrust is evolving toward a more critical state. Subsurface fluid pressure anomalies, measured by borehole instruments in a 2024 Seismological Research Letters article, have increased by 5–7 MPa in the accretionary prism off Vancouver Island since 2018. An increase of 5–7 MPa, which corresponds to tens of atmospheres of additional pressure, is not a trivial change in the mechanical environment of the fault. In an accretionary prism, where sediments are already weak and highly fractured, rising pore pressure can reduce the effective normal stress that clamps the fault shut, making it easier for slip to occur.

These borehole observations dovetail with broader models of how fluids influence slow slip and tremor in the Cascadia Subduction Zone. When combined with the detection of 20–30 Hz infrasound rumbles tied to fluid migration 40 km deep, the 5–7 MPa pressure increase suggests a multi-depth system in which fluids are becoming more mobile and more pressurized. For offshore infrastructure, including undersea cables and potential energy projects, a more weakly coupled accretionary prism raises the risk of submarine landslides and seafloor deformation during a future megathrust event. For coastal residents on Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland, elevated fluid pressures are another reason to treat Cascadia’s apparent quiet as deceptive; the fault is being primed from below by processes that cannot be seen at the surface but are now being captured by sensitive borehole instrumentation.

9. 324-Year Inter-Event Gap Approaching Critical Threshold

The lengthening inter-event gap since the last full-margin rupture is perhaps the most sobering red flag of all. Historical recurrence intervals from Chris Goldfinger’s 2019 Oregon State University analysis show megaquakes every 200–500 years, with the current inter-event time at 324 years and accelerating precursors. That range of 200–500 years reflects variability in how often the Cascadia Subduction Zone has produced great earthquakes over the past several thousand years, based on turbidite deposits, coastal subsidence records, and tsunami sands. Sitting at 324 years since the January 26, 1700 event, Cascadia is now squarely within that historical window, and the mention of accelerating precursors aligns with the recent observations of faster slow-slip rates, more deep tremors, and rising microseismicity.

Other paleoseismic work has reinforced the idea that the margin is capable of maximum ruptures that span central and southern Cascadia, consistent with the 1700 event and the modeled scenarios that produce 4–6 minutes of shaking in Portland. When those long-term recurrence statistics are combined with modern geodetic estimates of 2–3 cm per year of locked convergence and the recognition that ETS episodes can accommodate up to 40 m of slip at depth, the conclusion is difficult to avoid: the system is aging toward its next great earthquake. For policymakers, the 324-year inter-event gap is not a countdown clock but a probabilistic warning that the odds of a megathrust event are rising within the planning horizon of major infrastructure, from replacement bridges in Portland to seismic retrofits in Seattle and Vancouver. As I weigh the converging evidence, the pattern of accelerating slow slip, heightened tremor activity, fluid pressure anomalies, and a maturing recurrence interval together form a compelling case that Cascadia’s next megaquake is not a distant abstraction but a looming, if still unscheduled, reality.

More from MorningOverview