Across history, a handful of people have described future events with such eerie accuracy that their words still unsettle readers today. From shipwrecks and space travel to global war and handheld technology, these six cases show how imagination, intuition, and close observation can sometimes look a lot like time travel. I will walk through each one, grounding the stories in documented facts while asking what it means when fiction and foresight collide.

1. The Novelist Who Foresaw the Titanic Disaster

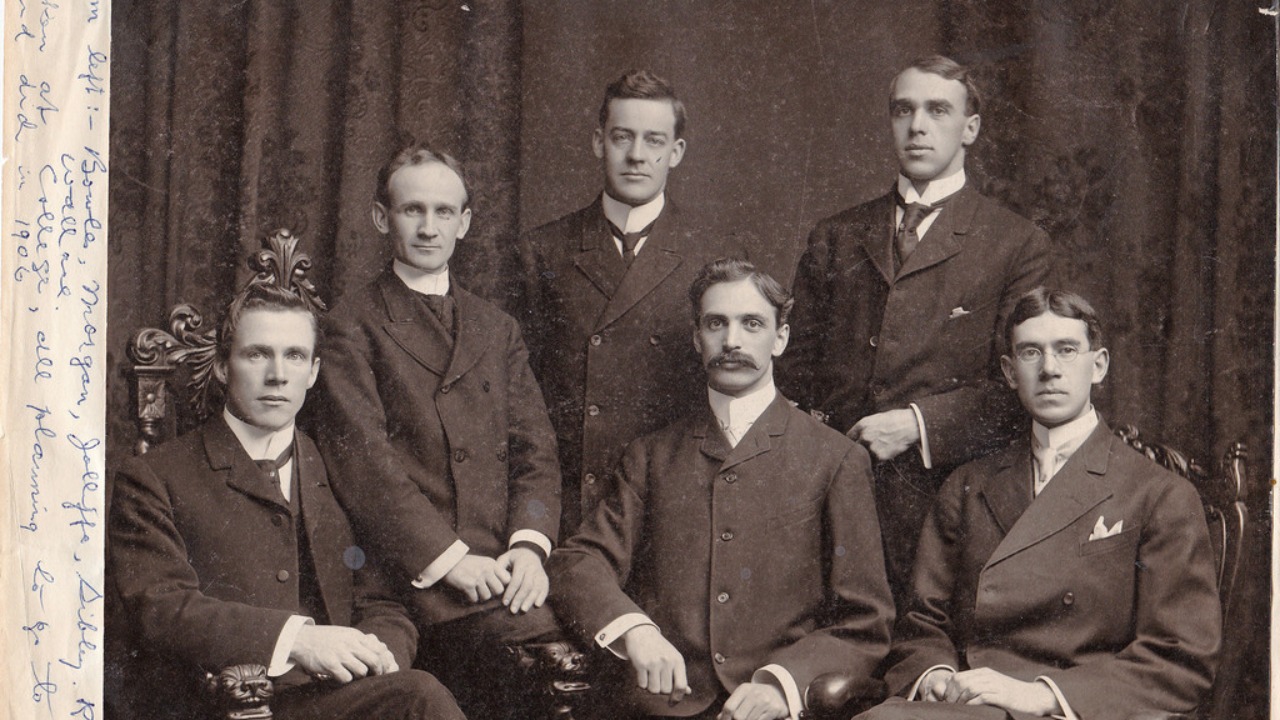

Morgan Robertson’s 1898 novel “Futility, or the Wreck of the Titan” is one of the most striking examples of a writer apparently anticipating a real catastrophe. In the story, he describes a gigantic luxury liner called the Titan, promoted as “unsinkable,” measuring about 800 feet long and crossing the North Atlantic on a cold April night. The fictional ship strikes an iceberg, lacks enough lifeboats for everyone on board, and sinks with a massive loss of life. In reality, the Titanic was 882 feet long and went down on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic, killing over 1,500 people, a set of parallels that a detailed literary analysis has laid out point by point.

Commentators have long debated whether Robertson was a prophet or simply an author who understood maritime risk. One discussion of how he seemed to anticipate both the Titanic and later conflict calls the resemblance “uncanny” and “very unsettling,” noting how closely his fictional ship tracks the real Titanic. Another account of maritime fiction points out that Two different stories, including one by W.T. Stead, also imagined eerily similar disasters, suggesting that experienced observers saw the danger in overconfident engineering long before 1912, a point underscored when a feature on those Two fictional stories described the parallels as “uncanny.” In one social-media retelling, the question “Was Morgan Robertson” a prophet is answered more cautiously, arguing that his sailing background and attention to lifeboat regulations helped him extrapolate a plausible worst case, a view highlighted in a widely shared Was Morgan Robertson post. For shipping regulators and engineers, the stakes were enormous: these fictional warnings foreshadowed the real-world push for stricter safety rules after the Titanic sank.

2. The Author Who Timed His Death with a Comet

Mark Twain’s connection to Halley’s Comet is one of the most famous coincidences in literary history. He was born in 1835, during the comet’s perihelion that year, and late in life he fixated on that celestial timing. In 1909, he reportedly said, “I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it,” a line that has been preserved in a detailed biographical profile of his life and work. Twain died on April 21, 1910, shortly after the comet became visible again in the night sky during its 1910 return, which made his remark feel chillingly prescient to contemporaries, even though the exact orbital perihelion occurred several weeks later. The eerie part is not a to-the-day prediction of an astronomical event, but the way he publicly tied his fate to a specific cosmic cycle and then died during that same appearance.

For readers and historians, the stakes of this coincidence go beyond curiosity about one man’s death. Twain’s remark shows how a writer who spent his career skewering superstition could still indulge in a kind of poetic fatalism about his own life. The fact that he singled out Halley’s Comet, a predictable and well-documented phenomenon, suggests he was thinking about how individual lives intersect with long, measurable cycles of time. When the comet returned and he died within that same window, admirers saw it as a narrative ending worthy of one of his own stories. It also illustrates how people often retrofit meaning onto events, reading cosmic significance into timing that, from a scientific perspective, is coincidental but, from a cultural perspective, feels like a powerful symbol.

3. The Sci-Fi Pioneer Who Invented the Tank

H.G. Wells’s 1903 short story “The Land Ironclads” is frequently cited as a blueprint for the modern tank. In that tale, he imagines massive armored vehicles moving on continuous tracks, crossing rough battlefields that stop ordinary infantry. These machines carry rapid-fire guns and crews of specialized operators, and they are deployed to break a stalemate that looks strikingly like trench warfare. A historical overview of Wells’s work on future conflict notes that these fictional “land ironclads” anticipated the tracked armored vehicles that first appeared on World War I battlefields in 1916, when tanks were introduced to punch through entrenched lines, a connection explored in depth in a study of Wells’s foresight.

What makes Wells’s prediction so compelling is not just that he imagined an armored vehicle, but that he understood how such machines would change tactics and strategy. In his story, the land ironclads are not invincible, yet they dominate open ground and force traditional armies to rethink their defenses, much as real tanks did when they rolled into the trenches of the Western Front. For military historians and defense planners, this kind of fiction matters because it shows how speculative writing can anticipate the social and logistical impact of new technology, not only its hardware. Wells’s work has been grouped with other books that seemed to look 100 years ahead, part of a broader pattern in which Many authors have described inventions and events far in advance, a trend highlighted in a discussion of how Many writers predicted the next 100 years. His land ironclads remind readers that ideas about future warfare can shape, and sometimes even accelerate, the weapons that later appear.

4. The Visionary Who Mapped the Moon Landing

Jules Verne’s 1865 novel “From the Earth to the Moon” is often held up as a stunning early sketch of crewed spaceflight. In the book, Verne describes a cannon-launched spacecraft fired from Florida, carrying three men on a journey to the Moon before splashing down in the Pacific Ocean. More than a century later, Apollo 11 launched from Florida in 1969 with three astronauts on board and returned with a splashdown in the Pacific, a set of parallels that a detailed historical review has compared point by point. Verne’s fictional method of launch, a giant cannon, was not how NASA ultimately solved the problem, but his choices of launch site, crew size, and ocean recovery zone line up so closely with Apollo that they still surprise space historians.

Readers and researchers have continued to probe how Verne arrived at these details. One discussion among fans notes that in Vernes novel “From the Earth to the Moon,” he gets several eerie predictions right about the Apollo 11 launch, and that enthusiasts have even used a poll to gauge how familiar people are with those specific overlaps, a point raised in a poll of Verne readers. For space agencies and science communicators, Verne’s work shows how imaginative fiction can inspire real engineers, providing a narrative framework that later missions either follow or consciously reject. His story also underscores how carefully reasoned speculation, grounded in the physics and geography known in the 1860s, can end up looking like prophecy when technology finally catches up.

5. The Inventor Who Dreamed Up the Smartphone

Nikola Tesla’s 1926 interview with Collier’s magazine contains one of the clearest early descriptions of something that looks like a modern smartphone. In that conversation, he predicted that people would one day carry “a pocket device” that would allow global wireless communication. He envisioned users being able to see and hear one another anywhere on Earth, using pocket-sized receivers that would fit easily into a vest or coat. A transcript of Tesla’s remarks notes that he described a worldwide system of wireless connections that would make information instantly available, an idea that closely anticipates mobile phones and video calls, as summarized in a detailed account of Tesla’s predictions.

The stakes of Tesla’s foresight are particularly clear for technologists and historians of innovation. At a time when radio was still relatively new, he was already thinking about miniaturization, user-friendly interfaces, and the social impact of constant connectivity. His “pocket device” sounds remarkably like a smartphone running apps such as FaceTime or WhatsApp, which now make it routine to see and hear people globally in real time. Tesla’s comments also highlight how visionary thinkers can extrapolate from existing technologies to imagine entire ecosystems of future devices. For today’s engineers and policy makers, his predictions are a reminder that the social consequences of new tools, from privacy concerns to information overload, can be as important as the hardware itself, and that anticipating those consequences is part of responsible innovation.

6. The ‘Sleeping Prophet’ Who Saw World War II Coming

Edgar Cayce, often called the “Sleeping Prophet,” delivered a series of psychic readings in the 1930s that his followers believe anticipated World War II. In those sessions, he warned of a “second great war” that would begin around 1936, involving both Europe and Asia, and linked its outbreak to a global economic collapse. A summary of his readings notes that he tied rising tensions to the worsening Great Depression, which deepened in 1936, and that his timeline pointed toward a conflict that would eventually be recognized as World War II, which began in 1939, a sequence laid out in detail in an overview of Cayce’s prophecies. While his dates do not match the official start of the war exactly, the broad contours of his warning, a global conflict spanning Europe and Asia emerging from economic turmoil, align closely with what unfolded.

For historians and skeptics, Cayce’s case raises difficult questions about how to evaluate predictions that are partly right and partly wrong. His reference to 1936, for example, can be read as a miss if one focuses strictly on the invasion of Poland in 1939, or as a partial hit if one emphasizes the intensifying crises and rearmament of the mid-1930s. Supporters argue that his emphasis on economic collapse and geopolitical fault lines shows genuine insight into the forces driving the world toward war. Critics counter that talk of another major conflict in that era was common among analysts who watched fascism rise and international agreements fray. Either way, Cayce’s readings illustrate how people look to seers and forecasters when the global order feels unstable, and how, in hindsight, even ambiguous warnings can take on an aura of eerie accuracy when history moves in the feared direction.

More from MorningOverview