The Apollo Moon landings are among the most dissected events in history, yet some of their strangest details still hide in the fine print. I have pulled together 10 insane Apollo Moon landing facts you probably never heard, each grounded in documented mission records and specialist reporting. From the smell of lunar dust to improvised life insurance, these stories reveal how bizarre, risky and improvised the race to the Moon really was.

Apollo employed nearly half a million people

The scale of Apollo was so vast that it employed “nearly half a million people,” a figure documented in detailed program histories and echoed in Things You May Not Know About the Apollo Program. Engineers, machinists, seamstresses, test pilots and administrators were spread across the United States, all feeding into a single goal of landing humans on the Moon. That workforce stitched together everything from pressure suits to guidance computers.

Such a gigantic payroll meant Apollo functioned as an industrial policy as much as a scientific project, distributing contracts to universities and companies in dozens of states. The stakes were not only geopolitical, with the United States racing the Soviet Union, but also economic, because hundreds of thousands of jobs depended on continued funding. I see this as one reason the program could sustain political support despite its enormous cost.

The first Saturn V crew unexpectedly went to the Moon

The Saturn V was so powerful and untested that early plans kept it in Earth orbit, yet Apollo 8’s crew became the first humans to ride it all the way to the Moon. According to mission histories, the original idea was a lower risk flight that did not leave Earth orbit, but changing intelligence about Soviet plans pushed NASA to send Apollo 8 into lunar orbit instead. As Saturn launch analyses note, this meant the first crewed Saturn V flight also became the first to escape Earth’s gravity.

That decision compressed testing schedules and forced astronauts to accept unprecedented risk, because no one had flown the rocket with people on top before. Strategically, it signaled that Apollo and the United States were willing to gamble to stay ahead in the race to the Moon. I view Apollo 8 as the moment the program shifted from cautious engineering to bold geopolitical maneuvering.

Apollo 11 astronauts used postcards as life insurance

The Apol 11 crew faced a very real chance of not returning, yet traditional life insurance was either unavailable or prohibitively expensive for astronauts. Reporting on Postcards explains that Jul mission planners and the astronauts devised a workaround: Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins signed stacks of commemorative covers before launch. Friends quietly postmarked them on key dates, creating collectibles that families could sell if disaster struck.

This improvised financial safety net highlights how experimental Apollo really was, even in basic matters like survivor benefits. It also shows the astronauts’ awareness that their fame had monetary value independent of their salaries. I find it striking that one of the most advanced technological feats in history relied on such a low-tech, almost quaint, form of life insurance.

Moon dirt smells like spent gunpowder

When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin tracked lunar dust back into the lunar module, they discovered that Moon dirt smells like spent gunpowder. Accounts collected in Little Known Facts About the Moon Landing describe how the fine, glassy particles clung to suits and boots, then released a sharp, metallic odor in the cabin. When Neil Armstrong first reported the smell, scientists were surprised, because vacuum-baked regolith samples on Earth did not reproduce it.

The discrepancy underscores how alien the lunar environment is, with dust that is jagged, electrostatically charged and unlike any soil on Earth. For astronauts, the clingy particles were more than a curiosity, they posed risks to seals, radiators and lungs. I see this as a reminder that even “dead” worlds can challenge human bodies in ways that are hard to simulate beforehand.

Apollo’s workforce was mapped by poll-like surveys

Behind the scenes, Apollo managers relied on detailed surveys, similar to a poll, to track how resources and personnel were distributed across the program. Documentation on Apollo notes that these efforts quantified how many contractors, engineers and support staff were tied to each major subsystem. By treating the workforce almost like a sampled population, planners could argue for continued funding by pointing to specific job counts in key congressional districts.

This quasi-poll approach turned raw employment numbers into a political tool, reinforcing Apollo’s status as a national project rather than a niche scientific mission. It also foreshadowed modern data-driven lobbying, where granular statistics shape budget debates. I interpret this as evidence that Apollo’s success depended as much on political analytics as on rocket science.

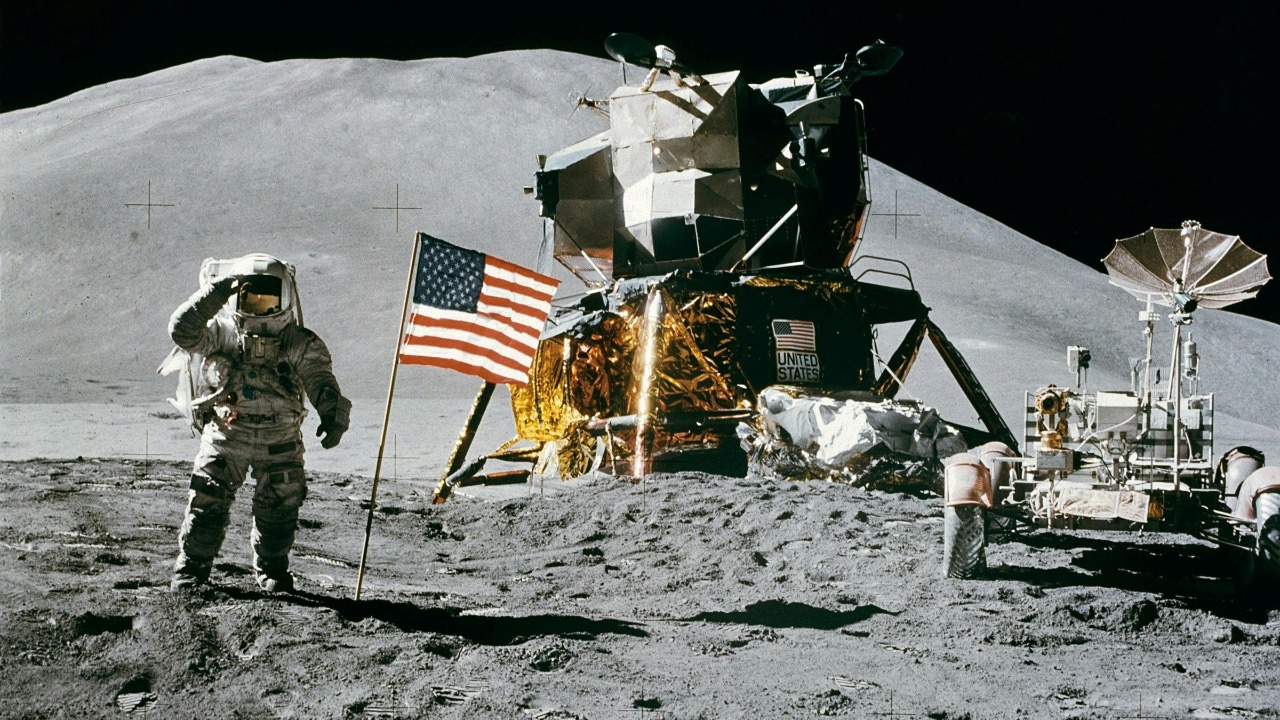

The Moon is now an astronaut junkyard

The Apollo Mission left the Moon littered with hardware, from descent stages to experiment packages, creating what one analysis bluntly calls an “astronaut junkyard.” According to The Apollo Mission records, the most famous relic is the Apollo 17 Lunar Module “Challenger” descent stage, still sitting in the Taurus-Littrow valley. Other missions left seismometers, reflectors and even personal items on the surface.

These abandoned artifacts are scientifically valuable, because retroreflectors still help measure the Moon’s distance, but they also raise questions about preservation and contamination. Future crews and robotic missions will have to decide whether to treat these sites as archaeological zones or scrap yards. I see the lunar junkyard as the first test case for heritage management beyond Earth.

Apollo 11 nearly ran out of fuel during landing

There were three crew members on Apollo 11, but only Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin descended to the surface, and their landing came perilously close to failure. Mission transcripts cited in Here show that alarms, boulder fields and navigation errors forced Armstrong to take manual control and search for a safer spot. Controllers later calculated that the lunar module had only seconds of fuel remaining when it finally touched down.

The razor-thin margin illustrates how unforgiving the descent was, with no practical abort option once the engine was throttling toward the surface. For mission planners, the episode validated the decision to train astronauts as test pilots capable of improvisation, not just passengers. I regard this near miss as one of the clearest examples of human judgment saving a high-tech mission.

Moon soil is extremely clingy and hazardous

Beyond its smell, Moon soil is extremely clingy, a property that created constant headaches for Apollo crews. Detailed surface reports compiled in Here describe how the jagged grains stuck to suits, tools and visors, refusing to brush off easily. Unlike rounded Earth dust, lunar regolith is sharp-edged because it has never been weathered by wind or water, so it can abrade seals and fabrics.

For astronauts, this meant more than dirty equipment, it threatened the integrity of life-support systems and could irritate lungs if particles entered the cabin. Strategically, the problem has become a major design driver for future Moon bases, which must handle dust over months or years. I see lunar dust as one of the most underestimated engineering challenges in human spaceflight.

Mission Control used quirky nicknames and checklists

Inside Mission Control, controllers developed a culture of nicknames, in-jokes and obsessively detailed checklists that kept Apollo 11 on track. Compilations of Out World Apollo Facts note that Mission Control referred to specific procedures and alarms with shorthand labels that only insiders fully understood. These terms appeared on printed checklists that astronauts and controllers followed line by line, even during emergencies.

This culture of ritualized procedure, wrapped in informal language, helped teams stay calm under pressure by turning life-or-death steps into familiar routines. It also shows how human factors, like shared humor and jargon, can be as important as hardware reliability. I think of these nicknames as the social software that made the technical software usable in crisis.

Astronauts left 96 bags of human waste on the Moon

Among the strangest legacies of Apollo is the fact that astronauts left 96 bags of human waste scattered across six landing sites. Detailed inventories of things left on the Moon list these sealed bags alongside discarded tools and equipment. They were jettisoned to save weight for ascent, a trade-off that prioritized bringing back rocks and instruments over returning every piece of trash.

Those waste bags now represent an accidental biological experiment, preserving human microbes in a harsh, airless environment for decades. Future missions may study them to see how life endures in deep space conditions, turning garbage into data. I find it fitting that one of Apollo’s most enduring scientific opportunities may come from something the crews were desperate to get rid of.

More from Morning Overview