China’s decision to halt work on what was meant to be the world’s largest particle accelerator has reshaped the global race to probe the Higgs boson and the fabric of the universe. Instead of cementing a new scientific superpower, the pause on the Circular Electron Positron Collider, or CEPC, has handed fresh momentum to Europe and revived questions about how far even the biggest economies are willing to go for fundamental physics. I see the move as a revealing stress test of China’s economic priorities, its technological ambitions, and the limits of megaproject science in a more uncertain world.

From bold Higgs dream to abrupt pause

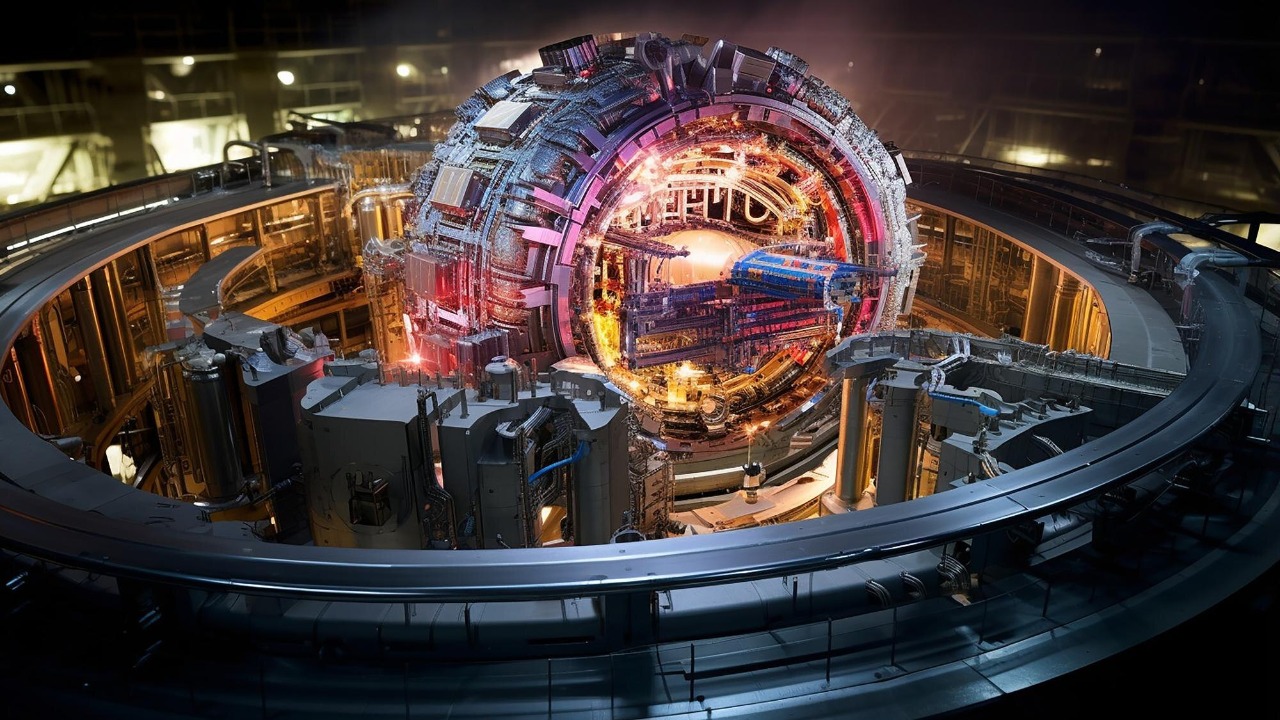

When planners first sketched out the Circular Electron Positron Collider, they were not thinking small. The CEPC was designed as a 62‑mile ring, a so‑called “Higgs factory” that would smash electrons and positrons together with unprecedented precision to study the Higgs boson, the same particle that Development for CEPC scientists at CERN first confirmed in proton collisions. The vision was straightforward and audacious: build the largest collider on Earth, leapfrog existing facilities, and turn China into the place where the next generation of particle physics discoveries would be made.

That ambition has now run into a hard stop. Reports describe how China halts world’s largest ‘Higgs factory’, shelving the 62‑mile “God particle” collider just as the project had entered a detailed technical phase. The facility, planned at the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing, was supposed to be the centerpiece of a long‑term strategy to dominate high‑energy physics. Instead, the pause has turned the CEPC into a case study in how even the most ambitious scientific dreams can be overtaken by cost, politics, and shifting national priorities.

How the CEPC was meant to change particle physics

The scientific case for the CEPC was always about precision rather than brute force. Where CERN’s Large Hadron Collider uses proton collisions to discover new particles, the CEPC’s electron‑positron design promised cleaner data and far more detailed measurements of the Higgs boson’s properties. By observing how the Higgs interacts with other particles, researchers hoped to test the Standard Model to its limits and search for subtle deviations that might hint at new physics, a goal that was central when CERN discovered the Higgs and remains just as urgent today.

In that sense, the CEPC was never just a bigger machine, it was a different kind of instrument. It would have complemented, not simply competed with, existing colliders by turning the Higgs into a precision tool for exploring the quantum world. The project’s backers argued that a dedicated Higgs factory could reveal new forces or particles indirectly, through tiny anomalies in decay rates and coupling strengths that only a machine of this scale could resolve. With China halts world’s largest ‘Higgs factory’, giving West edge in ‘God particle research, that scientific roadmap is now in flux, and the burden of pushing Higgs physics forward is shifting back toward Europe and other potential collider hosts.

Too expensive even for China

Cost, more than any technical hurdle, appears to have been the decisive factor. Building a 62‑mile underground ring, outfitting it with cutting‑edge magnets, detectors, and power systems, and then operating it for decades would have required a financial commitment on the scale of a national infrastructure program. Reporting on the pause has framed the decision bluntly as Too expensive even for China, a sign that the price tag of this ambitious race with Europe simply became too hard to justify in the current economic climate.

That phrase matters because it captures a broader shift in how Beijing is weighing prestige projects against more immediate pressures. Slower growth, a property downturn, and the need to shore up domestic employment all compete for the same pool of public resources that would have funded the CEPC. When a government that has poured money into high‑speed rail, space stations, and industrial subsidies decides that a collider is a bridge too far, it signals a recalibration of what counts as strategic science. The CEPC’s shelving suggests that even for China’s leadership, the political return on a multibillion‑dollar Higgs factory no longer outweighs the opportunity cost of tying up that capital for decades.

Europe’s FCC suddenly looks less “excessive”

The pause in Beijing has landed like a gift in Geneva. At CERN’s campus in MEYRIN, officials have been working on their own next‑generation collider, the Future Circular Collider, or FCC, which would dwarf even the Large Hadron Collider in size and energy. Critics have long argued that The FCC, which could become operational by the end of the 2040s, is excessive, especially in an era of tight public budgets and competing scientific priorities. Yet with China stepping back, the FCC is no longer just one option among several, it is rapidly becoming the only credible path to a truly next‑generation collider.

That shift has not gone unnoticed inside CERN. The lab’s director has been openly upbeat about CERN, China and the new landscape, noting that China’s decision to pause its mega‑project strengthens the case for Europe to press ahead. The FCC, once seen by some as a risky bet that might be undercut by a faster, cheaper Chinese rival, now looks like the default global flagship. In practical terms, that could make it easier to rally European Union governments and international partners behind the funding, since the fear of duplication has faded and the geopolitical argument for keeping leadership in Europe has grown stronger.

What the halt reveals about China’s science strategy

Stepping back from the CEPC does not mean Beijing is retreating from science, but it does reveal a more selective approach. Over the past decade, China has invested heavily in quantum communication, supercomputing, and space exploration, areas with clear military or commercial payoffs. A Higgs factory, by contrast, is the epitome of curiosity‑driven research, with benefits that are diffuse, long term, and hard to translate into immediate power. The decision to pause the collider suggests that, when trade‑offs bite, projects with a direct link to economic or security goals will win out over pure discovery.

There is also a reputational dimension. The CEPC was a way for China to show that it could not only catch up with Western science but set the global agenda. Halting the project risks signaling that the country is less willing to shoulder the open‑ended costs of being a scientific superpower. At the same time, it may reflect a confidence that China can still shape high‑energy physics through collaboration, detector technology, and theory, even without hosting the biggest machine. The fact that Development of the CEPC had already reached a detailed technical phase before being shelved underscores how far the planning had gone, and how deliberate the choice to stop now must have been.

The West’s edge in the “God particle” race

For scientists in Europe and North America, the immediate consequence of China’s pause is a strategic opening. With the CEPC off the table for now, the West has a clearer path to maintain leadership in Higgs physics and the broader search for new particles. Reports have framed the decision as giving West edge in ‘God particle research, a reminder that fundamental physics is not just about equations but also about influence, talent flows, and technological spin‑offs.

That edge is not automatic, however. Europe still has to find the money and political will to build the FCC, and the United States has its own debates about whether to re‑enter the collider game in a serious way. What China’s move does is remove a powerful argument against Western investment, namely the fear of being outpaced by a cheaper, faster rival in Beijing. With China, Higgs ambitions on hold, Western policymakers can now frame their own projects as essential to keeping the frontier of particle physics in democratic hands, rather than as a costly duplication of someone else’s megaproject.

Domestic trade‑offs and the politics of big science

Inside China, the CEPC pause also reflects a more domestic calculus. Large‑scale science projects compete with infrastructure, social spending, and industrial policy for finite state resources. In a period of economic uncertainty, it is politically easier to justify investments that create visible jobs or shore up struggling sectors than to pour money into a collider that, for most citizens, will remain an abstract symbol of prestige. The framing that the collider was China, Europe’s most ambitious race in particle physics underscores how much of the project’s value was tied to international status rather than domestic utility.

There is also the question of scientific community expectations. Chinese physicists who had built careers around the CEPC now face uncertainty about their future research paths, and some may look abroad for opportunities at CERN or other labs. That brain‑drain risk is part of the political equation. By halting the collider, Beijing saves money in the short term but may lose some of the human capital it has spent years cultivating. The balance between fiscal prudence and long‑term scientific capacity is delicate, and the CEPC decision shows how easily it can tip when macroeconomic headwinds rise.

What comes next for global collider science

The shelving of the CEPC does not end the story of next‑generation colliders, it simply shifts the center of gravity. In Europe, the focus will intensify on securing commitments for the FCC and on upgrading the existing Large Hadron Collider to squeeze out as much physics as possible while a new machine is still on the drawing board. In China, the technical work already done for the CEPC could be banked for a future revival if economic conditions improve or if international partners step in to share the cost. For now, though, the world’s largest planned collider is in limbo, and the initiative lies elsewhere.

At a deeper level, the CEPC pause forces the global physics community to confront a hard question: how many multi‑billion‑dollar machines can the world realistically support, and where should they be built. The answer will depend not only on scientific merit but on geopolitics, public opinion, and the willingness of leaders to defend long‑term curiosity‑driven research in an age of short attention spans. With MEYRIN, CERN now more optimistic and Beijing more cautious, the balance of that debate has shifted. Whether it leads to a new era of coordinated global planning or a more fragmented, regional approach to big science is the next chapter that physicists, and politicians, will have to write.

More from MorningOverview