Cancer’s cruelest trick is its ability to disappear, only to reappear years later in a new organ or a familiar scar. The fear of that return shapes every scan, every follow-up visit, and every decision about how hard to push treatment. To understand how to stop it, I have to start with the biology of lingering cells, the conditions that wake them up, and the new science that is finally learning how to keep them quiet or wipe them out.

Researchers are uncovering why some tumors come roaring back while others stay silent for decades, and the answers are reshaping how remission, surveillance, and “cure” are defined. From dormant cells that behave like primitive seeds to respiratory viruses and COVID infections that can jolt them awake, the story of recurrence is no longer just about what happens in the operating room or infusion suite, but about the body’s ecosystem over a lifetime.

What “remission” really means, and why it is not the end of the story

When doctors say a cancer is in remission, they are usually describing what they can see, not what definitively exists. Complete remission means no detectable tumor on scans or blood work, while partial remission reflects a major shrinkage, yet even in both scenarios, microscopic clusters of malignant cells can remain. As one clinical explanation of remission notes, Certain types of cancer may never completely go away, which is why some patients stay on long term drugs or periodic infusions even when imaging looks clear.

That is also why Treatment During Remission has become its own phase of care rather than an afterthought. Instead of assuming the job is done, oncologists now talk about “maintenance” or “consolidation” therapy to keep residual cells from regrouping, especially in blood cancers and hormone driven tumors. The same overview stresses that Apr discussions about remission must include what ongoing treatment, monitoring, and lifestyle changes will look like, because the line between remission and recurrence is drawn by those invisible cells that escaped the first round.

Why cancer comes back: the roots that survive first treatment

At its core, recurrence is a numbers and survival problem: if even a small fraction of malignant cells outlive surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or targeted drugs, they can eventually seed a new tumor. A detailed explanation of Why Cancer Comes Back describes how recurrent disease starts with cells that the first treatment did not fully remove or destroy, which then lie low in the body until conditions favor their growth again. These surviving cells may be tucked into lymph nodes, bone marrow, or tiny pockets of scar tissue that no scan can resolve.

Clinicians distinguish this process from a second, unrelated cancer that arises independently, but for patients the emotional impact can feel the same. The biology, however, is different, and it matters for strategy. Recurrent tumors are often harder to treat because the cells that survived the first assault are, by definition, tougher or more adaptable. That is why the NCI description of Recurrent disease emphasizes that the new tumor can behave differently from the original, even if it carries the same name and appears in the same organ.

Dormant cancer cells: the “sleeping” seeds of metastasis

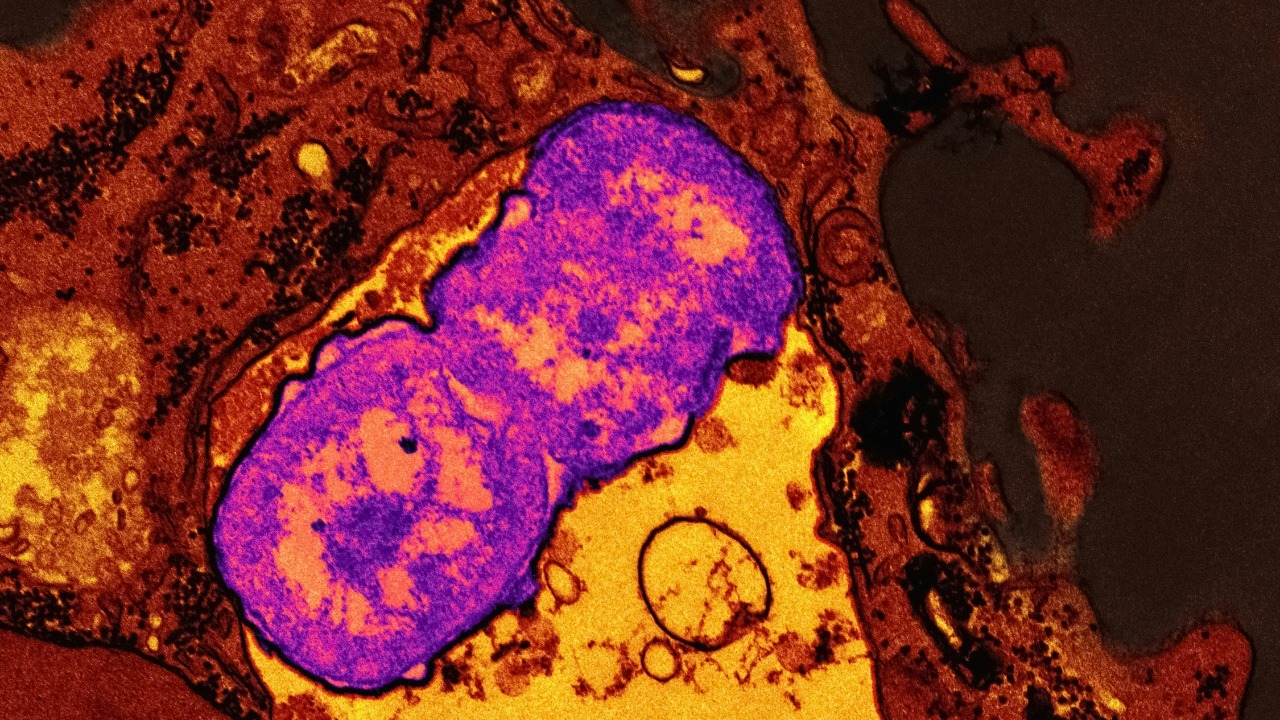

One of the most unsettling discoveries in oncology is that cancer cells can enter a dormant state, pausing their division for years while retaining the capacity to spread. In work highlighted by the NCI, researchers describe how They have the features of what are called primitive progenitor cells, a family of cells that can generate healthy tissue but, in this case, are co opted to seed metastases. These dormant cells can sit in organs like the lung, liver, or bone, essentially invisible to standard imaging and often less sensitive to chemotherapy that targets rapidly dividing cells.

Because these cells are quiescent, the immune system may tolerate them or fail to recognize them as a threat, allowing them to persist as a kind of biological time bomb. The same research underscores that their progenitor like traits help them adapt to new environments, which is why a breast tumor can later show up in bone or brain. Understanding how these dormant cells interact with surrounding tissue and immune defenses is now central to explaining why metastases can appear so long after the primary tumor was removed.

What wakes “sleeping” cancer cells: injury, infection, and inflammation

The mystery has never been just that dormant cells exist, but what flips them back into aggressive growth. Recent work described in Jan reporting on why cancer can come back points to shifts such as injury or illness that change the local tissue environment. Studies in the past few years have linked cellular damage and COVID infections to these awakenings, suggesting that when tissues are repairing themselves, growth signals and inflammatory molecules can inadvertently give dormant cancer cells a green light to start dividing again, a process detailed in the Jan analysis of cellular shifts.

Respiratory infections more broadly may play a similar role. An NIH summary of work on dormant tumors notes that What causes the cells to awaken has been unknown, but Studies have shown that cancer metastasis can be triggered by inflammation and that respiratory viruses may be one such spark. In this view, a bout of flu, COVID, or another viral illness is not “causing” cancer from scratch, but rather disturbing a fragile balance that had been keeping residual cells in check.

Resistance and evolution: when treatment itself shapes the comeback

Even when no obvious trigger like infection is present, cancer can return because the surviving cells have evolved to resist the very drugs that once shrank the tumor. A detailed overview of why some cancers come back explains that Cancers can become resistant to treatment as their cells accumulate new mutations and become more and more abnormal. In practice, that means a drug that once fit neatly into a tumor’s molecular “lock” no longer works because the lock has changed shape.

This evolutionary arms race is especially visible with targeted therapies and hormone blockers, which can hold disease in check for years before a resistant clone takes over. The same explanation notes that resistance can develop to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted cancer drugs alike, forcing oncologists to switch regimens or combine treatments to stay ahead. For patients, the message is not that treatment was pointless, but that it applied powerful selective pressure, killing off the most vulnerable cells and leaving behind those best equipped to adapt, which then drive the recurrence.

How often and where cancers return: patterns that shape follow up care

Not all cancers carry the same risk of coming back, and knowing those patterns helps tailor surveillance. A clinical overview of recurrence notes that While any cancer can come back, certain types are more likely to return, including cancers of the bladder and pancreas, as well as some breast and ovarian cancers. These tendencies influence how often patients are scanned, which blood markers are checked, and how aggressively doctors recommend ongoing therapy even when symptoms have resolved.

Location matters too. Some tumors tend to recur locally, near the original site or surgical scar, while others are notorious for distant metastases in organs like the liver, lung, or bone. That is why follow up plans often include both physical exams and specific diagnostic tests, from cystoscopies in bladder cancer to mammograms and MRIs in breast cancer. The same discussion emphasizes that improved imaging and diagnostic tests can catch recurrences earlier, when they are more treatable, but they also raise the emotional stakes of every scan, because patients know that a “clear” result today does not guarantee the future.

New frontiers: immunotherapy, CAR T cells, and targeting dormant cells

One of the most hopeful shifts in oncology is the move from simply shrinking visible tumors to reprogramming the immune system and microenvironment so that residual cells cannot easily return. A recent overview of Nov Key Facts on Advances in Cancer Treatment and Diagnostics notes that Immunotherapy has extended survival from months to years in some advanced cancers by helping the body recognize and attack malignant cells that would otherwise slip past. These therapies, including checkpoint inhibitors, are increasingly being tested in earlier stage disease to mop up microscopic remnants after surgery or chemotherapy.

More specialized approaches like CAR T cell therapy are also being refined with recurrence in mind. The same Nov summary explains that CAR T cell therapy represents a major leap in personalized Cancer Treatment and Diagnostics, and that in some trials CAR T cell therapy achieved deep remissions that may reduce relapse risk, as detailed in the companion analysis of Advances in Immunotherapy. In solid tumors, researchers are now designing trials that specifically track dormant cells and minimal residual disease, aiming to see whether immune based strategies can either eradicate these seeds or keep them permanently inactive.

Clinical trials and the hunt for “sleeping” cells

To stop late recurrences, scientists first need to find the cells responsible, which is why new trials are built around long term monitoring of minimal residual disease. In one Jan report, a patient named Dutton enrolled in a clinical trial called SURMOUNT as part of her treatment, a study designed to monitor her for sleeping cancer cells that could later wake and give rise to tumours. That kind of clinical trial uses sensitive blood tests, imaging, and sometimes biopsies over years, not months, to map how residual disease behaves.

Parallel work is testing drugs that specifically target dormant cells. In research highlighted in Sep coverage, scientists reported that Surprisingly, they have found that certain drugs that do not work against actively growing cancers can be very effective against dormant tumor cells, or can at least encourage those cells to remain dormant. That flips the old logic of chemotherapy on its head and suggests that the best way to prevent relapse may not always be to push cells into rapid death, but sometimes to lock them into a harmless sleep.

Cellular “noise” and the math of relapse

Beyond specific genes or pathways, some researchers are focusing on the randomness of cell behavior itself, the tiny fluctuations that can tip a cell from quiet to active. A recent report describes how Scientists have developed a new mathematical Noise model to understand how cellular noise can push a small subset of cells into states that resist treatment, leading to relapse or resistance. By simulating these stochastic shifts, they hope to design drug schedules or combinations that make it statistically less likely for a resistant clone to emerge.

The same work, highlighted by Drug Target Review, suggests that controlling noise might be as important as targeting specific mutations. If therapies can dampen the variability that lets a few cells “roll the dice” and survive, then even standard treatments could become more durable. It is an abstract idea, but it connects directly to the lived reality of patients who respond beautifully to a first line regimen, only to see the disease return from a handful of outliers that slipped through the cracks.

Lifestyle, stress, and food: what patients can control after treatment

While the biology of recurrence is complex, there is growing evidence that everyday choices can tilt the odds, even if they cannot guarantee an outcome. Guidance from a major cancer center on how stress affects risk emphasizes the importance of managing chronic strain on the body. The advice is blunt: Maintain a healthy lifestyle, Exercise regularly, eat healthy foods and prioritize getting enough sleep every night, because these habits support immune function and help us to better manage stress, which in turn may influence how the body handles residual cancer cells.

Diet is another lever. A detailed overview of 36 foods that can help lower cancer risk urges people to Focus on foods that come from plants, including whole grains, beans, nuts, and a wide range of fruits and vegetables, while limiting processed meats and sugary drinks that can increase your cancer risk. The same guidance notes that Just as there are foods that can reduce your cancer risk, there are also foods that can increase your cancer risk, underscoring that nutrition is not a magic shield but a meaningful part of the terrain in which dormant or resistant cells either thrive or struggle.

Hormones, medications, and structured prevention plans

For some cancers, especially hormone sensitive breast tumors, medications after initial treatment are a frontline defense against recurrence. A practical guide to creating a breast cancer recurrence prevention plan urges patients to Take control with a mix of Meds to more veggies, explaining that Studies have shown that anti estrogen therapies are among the medications that significantly reduce the risk of recurrence. These drugs, which block or lower estrogen, can starve residual hormone driven cells and are often prescribed for five to ten years after surgery and radiation.

The same Oct guidance stresses that lifestyle and medication work best together. Leaning into plant based foods, as well as fruits and vegetables, helps manage weight and metabolic health, which are themselves linked to recurrence risk in breast cancer. For patients, the message is that a prevention plan is not a single pill or rule, but a coordinated strategy that includes endocrine therapy, nutrition, physical activity, and regular follow up with oncology and primary care teams.

What oncologists watch for in remission: scans, bloodwork, and subtle signs

Once active treatment ends, the focus shifts to surveillance, and here both technology and clinical judgment matter. An educational video on preventing recurrence explains that Sep follow up visits often revolve around clarifying what remission means and what counts as a worrisome change. In that discussion of Preventing Cancer Recurrence, the speaker notes that a remission is when we do not see cancer cells by eye, but that counts can come back up and that is just the start of a conversation about next steps, not an automatic catastrophe.

Clinicians also rely on analogies to help patients understand why vigilance matters. One detailed explainer compares malignancy to a stubborn weed, noting that Why Do Some Cancer Cells Return is similar to asking why some roots remain after cutting a plant down. Think of the initial treatment as removing the visible growth, while Even a few remaining roots can eventually sprout again if the soil and weather are favorable. That is why regular scans, lab tests, and attention to new symptoms are framed not as living in fear, but as a way to catch any signs of recurrence early, when options are broader and outcomes better.

Where the science is heading: from fear of recurrence to long term control

As researchers map the biology of dormant cells, resistance, and environmental triggers, the goal is shifting from a binary cure versus relapse mindset to a more nuanced idea of long term control. In the Jan analysis of why cancer can come back, scientists describe how tracking cellular damage and infections like COVID can reveal windows when the risk of awakening dormant cells is higher, which could eventually guide timing of booster treatments or closer monitoring. That same work suggests that understanding these shifts at the single cell level may let doctors predict which patients are most vulnerable to late metastases and intervene earlier with targeted therapies.

At the same time, advances in immunotherapy, CAR T cells, hormone blockers, diet, stress management, and mathematical models of Noise are converging on a common aim: to make it harder for any surviving cell to find a path back to dominance. The science is not yet at the point where recurrence can be ruled out, and some mechanisms remain Unverified based on available sources, but the trajectory is clear. Each new insight into why cancer returns years later is also a blueprint for how to stop it, turning what once felt like an inevitable shadow into a risk that can be measured, managed, and, increasingly, pushed further into the distance.

More from Morning Overview