Within a few dozen light years of the Sun, the sky is crowded with stars that could, in principle, host living worlds. I want to know which of those neighbors are genuinely promising, not just famous names, and which kinds of stars give life the best odds. To answer that, I have to combine what we know about habitable zones, planetary habitability, and the growing census of nearby exoplanets

Instead of treating “Earth 2.0” as a vague slogan, I look at specific stellar systems around the Sun that check the key boxes: long-lived stars, stable environments, and planets that could keep liquid water on their surfaces for billions of years. That short list already includes familiar targets like Proxima Centauri and Alpha Centauri, but it is increasingly dominated by a quieter class of orange stars that may be even better than our own.

How I judge which nearby stars are truly promising

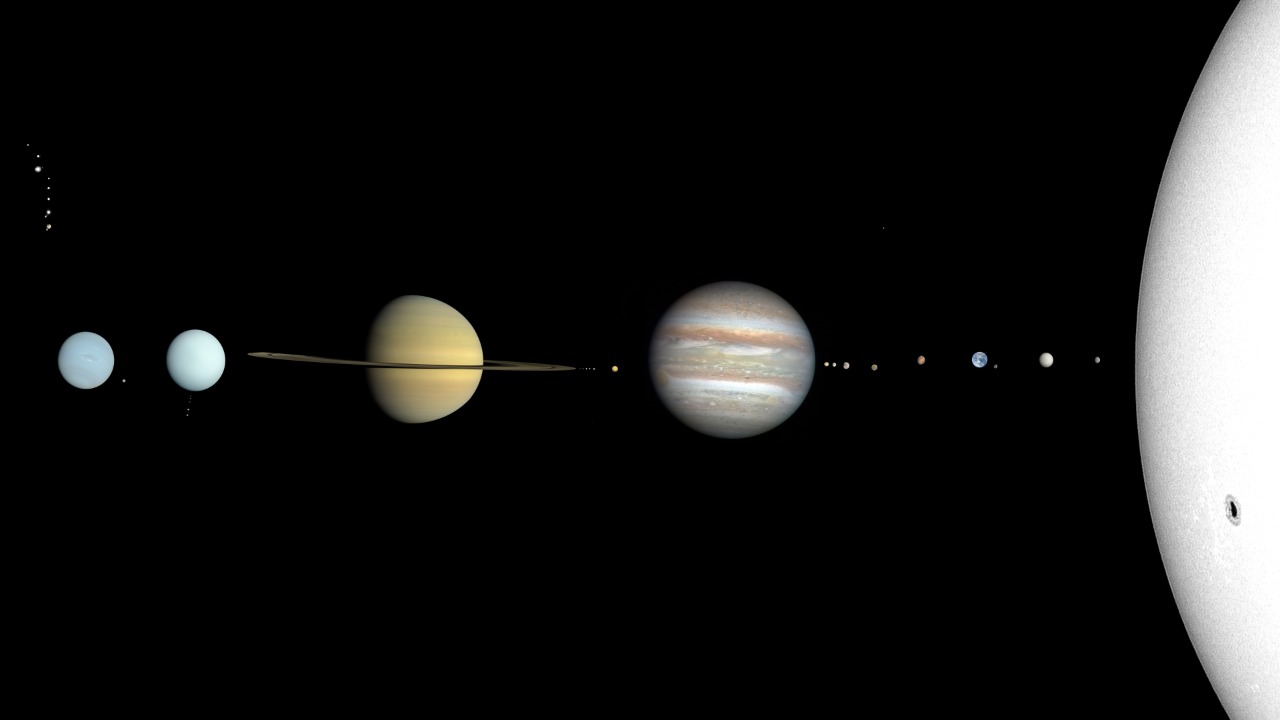

The first filter I apply is whether a star can keep a planet in the right temperature range for liquid water. The classic “habitable zone” is defined as the band around a star where a rocky world could maintain surface oceans under the right atmosphere, receiving roughly the same kind of energy balance that Earth gets from the Sun. As NASA notes, large gaseous worlds like Jupiter are far less likely to host life as we know it, so I focus on terrestrial planets that sit in that temperate band.

Liquid water alone is not enough, so my second filter is broader planetary habitability. A world can sit in the right orbit and still be sterile if it lacks a stable atmosphere, a protective magnetic field, or the right chemistry. As the concept of Liquid water makes clear, habitability is a function of many intertwined factors, from stellar radiation to planetary mass. When I rank nearby stars, I therefore privilege systems where we either know of terrestrial planets already or have strong reasons to expect them.

Why K-type dwarfs may be the best places to look

When I scan the neighborhood around the Sun, I keep coming back to K-type dwarf stars, the orange suns that sit between our G-type Sun and cooler red dwarfs. These stars are slightly smaller and dimmer than the Sun, but they burn their fuel more slowly and can stay stable for tens of billions of years. That extended lifetime means their habitable zones migrate outward more gradually, giving any planets in the right orbits far longer to develop and sustain biology. Work on K stars argues that this combination of longevity and gentle evolution makes them ideal places to search for life-bearing planets.

Earlier this year, Astronomers highlighted just how rich this category might be by flagging more than 500 nearby stars, many of them K-type, as strong candidates for hosting habitable planets. Because our own Sun has nurtured complex life for billions of years, it is tempting to treat it as the template, but detailed modeling suggests that slightly cooler orange dwarfs may actually offer more forgiving conditions. One analysis notes that, compared with our Sun, these stars can keep their habitable zones stable for an extra 1 or 2 billion years, a point underscored in work on K-type systems presented at the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Proxima Centauri and the perils of red dwarfs

Any list of nearby life-friendly stars has to start with Proxima Centauri, the closest stellar neighbor to the Solar System. The List of nearest exoplanets identifies Proxima Centauri as the star with the closest known planets, at a distance of 4.25 light years, and we already know of at least one terrestrial world in its orbit. Proxima Centauri b has become a flagship target because it sits in the star’s temperate zone and is roughly Earth sized, making it the nearest plausible candidate for a rocky, potentially wet planet beyond our system.

That proximity does not automatically make Proxima Centauri b a comfortable home. The planet orbits a small M-type red dwarf, and detailed assessments of Proxima Centauri stress that the star’s flares and high-energy radiation could strip away an atmosphere and complicate its habitability. Broader work on which stars can host alien life notes that M stars are stormy and that planets in their tight habitable zones are often tidally locked, with one side in permanent day and the other in endless night. As one analysis of M stars puts it, these systems “live fast, die young,” and their violent youth may bake or erode the very atmospheres life would need.

Alpha Centauri and other Sun-like neighbors

Just beyond Proxima lies the Alpha Centauri system, which I see as one of the most compelling nearby laboratories for life. Alpha Centauri contains two Sun-like stars and has long been a prime target for exoplanet searches. The Alpha Centauri entry in the list of nearest terrestrial exoplanet candidates notes that this system is the focus of several dedicated missions, including Breakthrough Starshot and Mission Centaur, which aim to find and eventually even visit nearby planets on timescales of decades rather than centuries.

Over the summer, Astronomers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to find strong evidence for a planet orbiting the closest Sun-like star in this triple system. The report on James Webb describes how the observatory picked up subtle signals consistent with a terrestrial planet that could, under the right conditions, host pools of liquid water on its surface. Because Alpha Centauri’s main stars resemble the Sun more closely than Proxima does, any planets in their habitable zones would avoid the most extreme flare activity of M dwarfs while still enjoying long, stable lifetimes.

Other nearby standouts within 25 light years

Beyond the Centauri system, several other nearby stars stand out as plausible hosts for life-bearing planets. Within roughly 25 light years, surveys have identified multiple terrestrial exoplanets orbiting small stars, including systems like Teegarden’s Star b and other compact red dwarfs. One overview of the most habitable exoplanets within that distance notes that About 75% of all stars in the sky are M-type red dwarfs, so it is no surprise that many of the closest known rocky planets orbit these cool, dim suns.

Some of the most intriguing candidates appear in the List of nearest terrestrial extrasolar planets, which catalogs the closest currently known rocky worlds that might be similar in size and temperature to Earth. Classic nearby targets like Epsilon Eridani, a star a bit smaller and cooler than our Sun located about 10.5 light years away in the constellation Eridanus, also remain on my shortlist. Work on Epsilon Eridani emphasizes that its youth and debris disk could signal ongoing planet formation, making it a natural place to look for emerging habitable worlds.

More from Morning Overview