In low-Earth orbit, a small California startup is trying to do something that sounds like science fiction: redirect sunlight so that night is no longer truly dark. The company, Reflect Orbital, wants to use a swarm of mirrors to bounce daylight onto cities and solar farms after sunset, promising cheaper power and safer streets but raising alarms from astronomers and dark-sky advocates. The idea could literally change how the planet experiences day and night, and the fight over it is quickly becoming a test case for who gets to reshape the sky.

From garage dream to orbital ambition

Reflect Orbital presents itself as a lean aerospace venture with a simple pitch: use space hardware to solve energy and lighting problems on the ground. On its own site, the company describes a plan to place reflective satellites in low orbit so they can steer sunlight to specific locations on Earth, effectively extending usable daylight for customers that pay for the service. The vision is not just about novelty lighting, it is framed as infrastructure, with the company positioning its constellation as a way to augment existing power grids and public lighting rather than replace them outright, a framing that helps explain why investors have taken the idea seriously enough to fund it.

That seriousness is underscored by the company’s early financing. Reflect Orbital has publicly announced a $20 million Series A that it says will accelerate development of its satellite constellation and support the company’s first space missions, a sizable sum for a still-unproven concept. On its main homepage, Reflect Orbital pitches the technology as a way to “turn on the sun” for customers on demand, a phrase that captures both the audacity of the project and the unease it provokes among scientists who see the night sky as shared heritage rather than a commercial billboard.

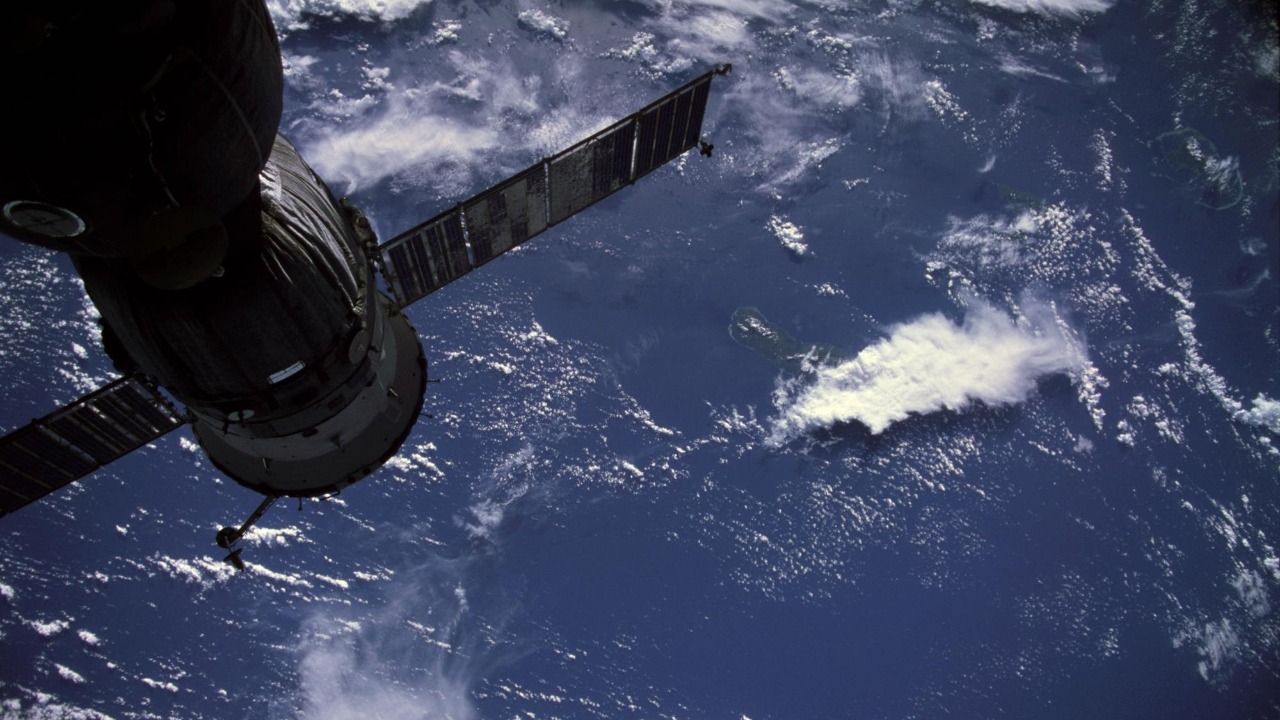

How a space mirror turns darkness into daylight

The core technology is conceptually straightforward: lightweight reflective surfaces in orbit catch sunlight and redirect it to a chosen patch of ground that is currently in darkness. According to technical descriptions of space-based reflectors, such space mirror systems rely on precise attitude control so that the mirror can maintain the correct angle between the Sun and the target on Earth, a nontrivial challenge when the hardware is racing overhead at thousands of kilometers per hour. Reflect Orbital’s concept builds on that basic physics but shrinks the hardware into many smaller units rather than a single giant reflector, trading complexity in control for flexibility in coverage.

Reporting on the company’s plans describes a constellation of thousands of thin, mylar-like reflectors in low-Earth orbit, each designed to brighten a region on the ground by a modest factor rather than flood it with blinding light. One analysis notes that Reflect Orbital would deploy thousands of these units in LEO to reflect sunlight onto Earth, with ambitions to scale from hundreds of satellites to as many as 250,000 long term if the business model holds. The company argues that, because each mirror is relatively small and the reflected light is spread over a wide area, the effect on the ground would resemble a bright twilight rather than a second sun, though critics question how controllable that glow would really be once multiplied across a global network.

The 4,000-mirror plan that set astronomers on edge

The controversy sharpened when Reflect Orbital moved from concept to regulatory filings. A series of reports describe how the California-based startup applied for a government license to launch a giant mirror to space as a pathfinder, then scale to a full constellation of 4,000 units. One detailed account notes that the California-based start-up Reflect Orbital wants to use those mirrors to extend daytime hours over selected regions, a prospect that some astronomers describe as “pretty catastrophic” from an observational perspective. The same reporting emphasizes that the company is not talking about a handful of experimental satellites but a large-scale commercial service that would be visible across wide swaths of the sky.

Additional coverage reinforces the scale of the ambition and the unease it has triggered. One piece characterizes the project as a plan to “sell sunlight” using giant mirrors in orbit, warning that the resulting skyglow could be “catastrophic” and “horrifying” for professional and amateur stargazers alike, with critics focusing on how a California-based startup Reflect Orbital might alter the night environment without broad public consent. Another report on the same 4,000-mirror proposal stresses that the constellation would be bright enough to interfere with sensitive instruments and long-exposure images, a concern echoed in a separate analysis that warns the constellation is going to produce a level of artificial brightness that current observatories are not designed to handle.

Licenses, regulators and a race to claim the sky

For a project that could reshape the night, the first real gatekeeper is not a global treaty body but a domestic communications regulator. Reflect Orbital, which is based in California, has requested a license from the Federal Communications Commission to launch a demonstration satellite that would reflect sunlight to power solar panels at night, a filing that effectively treats light as a service transmitted from orbit. The FCC’s role here is tied to spectrum and satellite operations rather than environmental review, which is why astronomers and dark-sky advocates worry that the licensing process may not fully account for the project’s impact on the shared sky. The fact that a single national regulator can greenlight a system visible worldwide highlights how fragmented space governance remains.

Other agencies and stakeholders are watching closely. A detailed examination of commercial space projects notes that Reflect Orbital’s website does not only highlight solar-power-boosting benefits but also advertises potential applications for defense customers, including the U.S. Air Force, which raises additional questions about how the mirrors might be used in conflict or surveillance scenarios. At the same time, a separate technical overview of solar power from space mirrors points out that such systems could direct energy to specific locations on Earth, an ability that is attractive for disaster response or remote communities but also politically sensitive if access to that light becomes a tool of leverage. The regulatory debate is therefore not just about brightness but about who controls a new kind of orbital infrastructure.

The promise: cheaper power, safer streets, new markets

Reflect Orbital’s pitch leans heavily on benefits that are easy to visualize. By bouncing sunlight onto solar farms after dark, the company says it can help panels keep generating power for hours beyond sunset, smoothing out the intermittency that plagues renewable energy. A feature on the company’s early growth describes how its founders see the mirrors as a way to “turn on the sun” for industrial sites, ports and remote communities, with one profile quoting co-founder Nowack on the advantages of building hardware in California, where machinists and precision laser suppliers are close at hand and satellite units can be produced for around €85,000 per unit. The company argues that, once in orbit, each mirror can serve multiple customers over its lifetime by redirecting light to different locations as demand shifts.

Beyond energy, the startup markets its system as a tool for public safety and economic activity. Its promotional materials and interviews suggest that illuminated streets and work sites could reduce crime and accidents, while extended daylight might boost productivity for construction, logistics and emergency response. A recent overview of the project frames it as a bold satellite initiative that aims to beam sunlight from space to Earth, describing a new venture by Reflect Orbital that could, in theory, help communities that currently rely on diesel generators or lack reliable grid connections. In that telling, the mirrors are less a gimmick than a new kind of infrastructure that might one day sit alongside undersea cables and GPS as invisible but essential space-based utilities.

The backlash: astronomers, dark skies and cultural loss

For astronomers, the upside is overshadowed by what they stand to lose. Ground-based observatories already struggle with interference from conventional satellites, and critics argue that a fleet of reflective mirrors designed to be bright enough to light the ground would be far more disruptive. A detailed science feature on Giant Mirrors in orbit notes that critics argue the satellites, billed as a way to harness sunlight after dark, would scatter light across the sky and contaminate long exposures, undermining efforts to study faint galaxies and near-Earth objects. The same reporting highlights that the startup has suggested it could begin operations as early as next year, a timeline that leaves little room for the global astronomy community to adapt.

Dark-sky advocates frame the issue even more broadly, as a question of environmental and cultural rights. DarkSky International has released an open letter opposing the project, warning that Reflect Orbital plans to launch a constellation that would significantly increase skyglow and create ecological and human health risks that likely outweigh the benefits. The group points to research on how artificial light at night disrupts migratory birds, insects and human circadian rhythms, arguing that a permanent artificial twilight from orbit would be far harder to mitigate than ground-based lighting. In that view, the night sky is not an empty canvas for commercial experimentation but a shared resource that should be protected much like oceans or national parks.

Money, scale and the long shadow of mega-projects

Behind the technical and ethical debate sits a blunt question: how big, and how expensive, could this become if it works? Historical analyses of space-based reflectors estimate that, at full scale, a fleet of mirrors large enough to significantly alter global lighting patterns could cost staggering sums. One widely cited assessment notes that, Overall, the estimated cost of constructing and sending a fleet of space mirrors to space is around 750 billion dollars, and adds that, If the system is scaled down, the price might drop to around 100 billion dollars. Reflect Orbital’s current fundraising is a tiny fraction of that, but the historical numbers illustrate how quickly costs can balloon when a concept moves from a few test units to a global network.

At the same time, the company and its backers argue that modern launch economics and mass-produced satellites change the equation. The profile that quotes Nowack on €85,000 per unit suggests that, if manufacturing and launch costs continue to fall, a constellation of thousands of mirrors could be built for a fraction of earlier estimates, especially if the satellites are small and ride to orbit as secondary payloads. Yet even a scaled-down system would still represent a major piece of orbital infrastructure, and a separate analysis of an ambitious proposal by US engineers to use space mirrors for solar power warns that such projects could threaten astronomy conducted from the ground even at relatively modest scales. The financial and technical feasibility, in other words, does not automatically resolve the question of whether the project is socially acceptable.

Who decides how bright the future should be?

As the debate intensifies, Reflect Orbital’s project is forcing a broader reckoning over who gets to make decisions about the sky. A detailed news feature on the controversy notes that a California startup’s plan to launch 4,000 mirrors has prompted scientists to call for a full environmental assessment before building the constellation, arguing that existing rules were written for communications satellites, not for orbiting floodlights. Another report on the same controversy emphasizes that, when you buy through links on coverage of the project, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission, a small but telling reminder that commercial incentives now run through every layer of the story, from the startup itself to the media ecosystem that covers it.

For now, the project sits at a crossroads. A long-form analysis of how California-based start-up Reflect Orbital is reshaping the conversation notes that astronomers are not opposed to all commercial activity in orbit, but they see this particular proposal as a tipping point that could normalize the idea of selling access to the night itself. A separate overview of a bold satellite project that aims to beam sunlight from space to Earth captures the stakes in a single image: a world where the boundary between day and night is no longer set by the planet’s rotation but by orbital contracts and control algorithms. Whether that future feels like progress or loss will depend on decisions being made now, in regulatory hearings and investor meetings, long before the first mirror unfurls in orbit.

More from MorningOverview