The newest generation of microrobots is so small that a single unit can perch on the ridge of a fingerprint and practically vanish from sight. Built at a scale that rivals grains of salt and human cells, these machines are not just tiny curiosities, they are fully programmable robots that can move, react and even “heal” in ways that hint at a new era of invisible automation.

Researchers are now demonstrating swarms of these devices swimming through liquid, marching across surfaces and responding to light, all while costing about as much as a copper coin. The result is a platform that could slip into medical devices, environmental sensors or industrial systems without ever being noticed by the naked eye.

How researchers shrank a robot to the edge of invisibility

The leap to robots that practically disappear starts with fabrication techniques that treat machines more like microchips than mechanical toys. I see the latest work from Researchers at Michigan and Pennsylvania as a direct extension of semiconductor-style manufacturing, where thousands of identical structures can be etched and assembled on a wafer, then released as free‑moving robots that each cost just a penny to produce. In that context, the phrase “world’s smallest programmable robots” is not marketing hype but a description of devices that are literally smaller than many dust particles.

In one set of experiments, University Researchers Debut Tiny Programmable Robots that are built in collaboration between teams in Michigan and Pennsylvania, using layered materials and integrated circuits to pack logic and motion into a footprint that rivals microscopic organisms. These Researchers have shown that the same batch processes used for electronics can churn out fleets of robots that are both programmable and cheap, a combination that is highlighted in reports that each unit can cost just a penny each, a price point that makes disposable swarms technically and economically plausible for the first time.

Smaller than salt, built for autonomy

Size alone would be impressive, but what makes these machines feel like a genuine turning point is their autonomy. I find it striking that Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the Universi of Michigan are not just shrinking motors, they are embedding simple decision‑making into robots that are smaller than a grain of table salt. At that scale, even basic behaviors like following a light source or changing direction in response to a chemical signal count as autonomy, because there is no tether, no external controller and no human hand guiding each move.

Reports on these systems describe how these autonomous robots are smaller than salt yet still manage to carry onboard circuitry that lets them respond to their environment, a capability that sets a new scale for programmable robots. In practice, that means a swarm of devices, each no bigger than a speck, can collectively navigate a fluid or surface using simple rules encoded in their tiny brains, a feat that is documented in coverage of how Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the Universi have created a new scale for programmable robots that operate without direct human control.

A robot that balances on a fingerprint

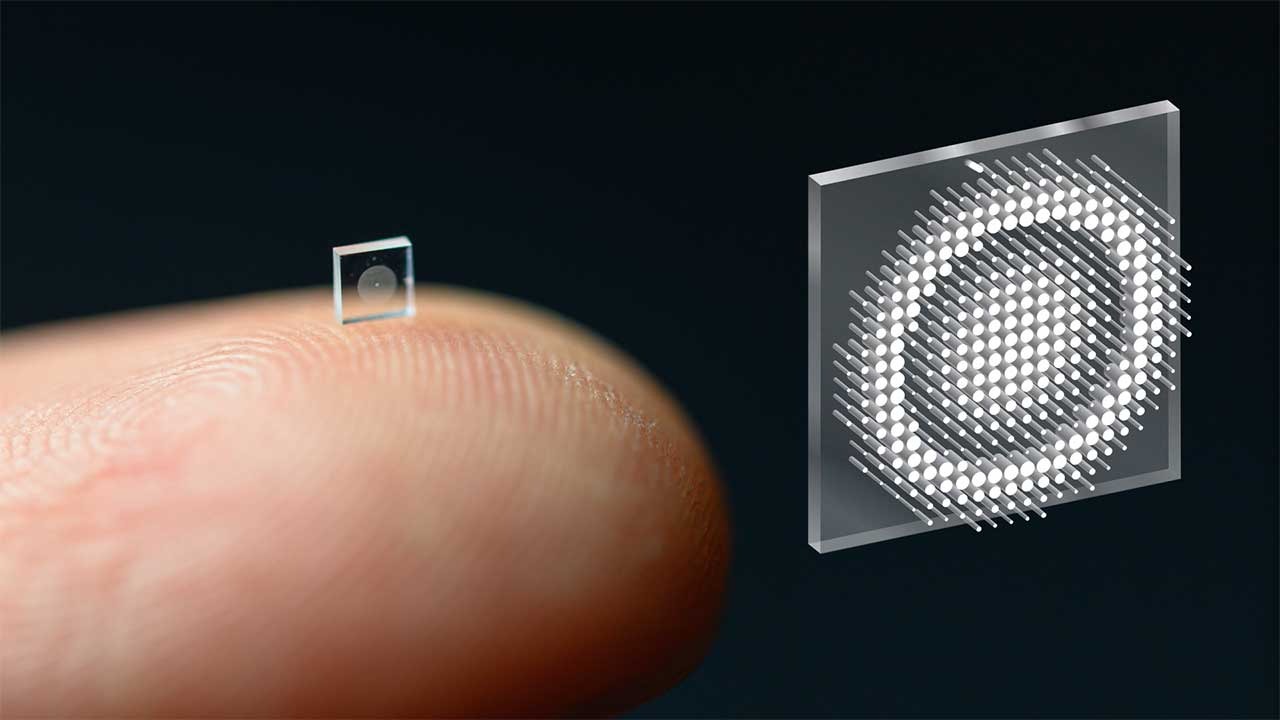

To appreciate how extreme this miniaturization is, it helps to picture a fingertip. The ridges that form a fingerprint are already fine enough that we use them for biometric security, yet the latest microrobot is so small it can balance on the ridge of a fingerprint and still leave room to spare. In coverage By Carly Cassella, the device is shown perched on human skin, a visual that drives home how easily you could brush it away without ever realizing a robot had been there.

The same reporting notes that the microrobot is so small it balances on the ridge of a fingerprint in an image captured by Marc, and that if you dropped one on a desk you might lose it instantly among ordinary dust. That scale is not a gimmick, it is a functional requirement for applications where robots must move through capillaries, cling to microscopic surfaces or slip into crevices that are invisible to the naked eye, and it is precisely this vanishingly small footprint that has led observers to remark that By Carly Cassella the microrobot is so small it balances on the ridge of a fingerprint in an image by Marc.

What “0.3 M” really means at this scale

When I read that light powers the world’s smallest programmable robot at About 0.3 M in length, the number initially feels abstract, but in practice it means a machine that is roughly a third of a millimeter long. At that dimension, the robot is only a few times larger than a human hair, and its thickness can approach the size of large cells, which is why researchers talk about integrating these devices into biological environments rather than just placing them on circuit boards. The phrase “About 0.3 M” is not a rounding error, it is a precise design target that balances the need for onboard electronics with the constraints of micro‑scale motion.

In technical descriptions, Light Powers the World, Smallest Programmable Robot, About, Millimeters Long, Learn how a pair of new studies use light both as a power source and as a control signal, allowing the robot’s limbs to flex when illuminated and relax when the light is removed. This approach eliminates bulky batteries and wires, which would be impossible at 0.3 M, and instead turns the surrounding light field into a kind of invisible joystick, a strategy that is detailed in analyses of how Light Powers the World, Smallest Programmable Robot, About, Millimeters Long, Learn to operate at a new scale for programmable robots.

Swimming, thinking and healing at the micro scale

What truly separates these devices from earlier micro‑machines is that They swim, think, and even respond to their environment, blurring the line between simple actuators and tiny robots with a hint of intelligence. I see this as the beginning of a shift from passive microstructures, which only move when pushed, to active microrobots that can sense, decide and act in ways that resemble primitive organisms. When Researchers describe these systems as autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller than conventional designs, they are underscoring how much functionality has been compressed into a volume that would once have held nothing more than a static sensor.

In practice, that means a single robot can swim through liquid using built‑in legs or fins, adjust its path when it encounters an obstacle and even “heal” minor damage by reconfiguring its structure or redistributing stress, behaviors that are highlighted in reports that They swim, think, and even respond to their environment as autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller. When multiplied across thousands of units, those capabilities could enable swarms that collectively map a bloodstream, clean a contaminated droplet or inspect microscopic cracks in industrial materials.

Balancing on a fingertip, built like a cell

Another striking detail is that the World, Smallest Programmable Autonomous Robots, Small Enough, Balance, Ridge of a fingertip, a phrase that captures both their scale and their mechanical robustness. I find the fingertip image compelling because it shows a robot that is not just tiny but also structurally complete, with legs, body and control elements all integrated into a package that can survive handling and still function. The fact that it can rest on the Ridge of a human finger without collapsing suggests that the underlying materials and fabrication methods are mature enough for real‑world use, not just laboratory demonstrations.

Technical breakdowns explain that these devices are built with bodies comparable in size to cells and are about 50 micrometers thick, dimensions that let them interact with biological tissue in ways that larger machines cannot. Researchers emphasize that the World’s Smallest Programmable Autonomous Robots are Small Enough to Balance on the Ridge of a Fingertip while still carrying functional components, a combination that is documented in coverage of how World, Smallest Programmable Autonomous Robots, Small Enough, Balance, Ridge of are built to match the scale of cells and 50 micrometers thick.

Brains, bodies and a one‑penny price tag

For all their delicacy, these robots are not fragile curios, they are engineered systems with brains, bodies and a business case. Scientists at the University of Pennsylvania, working with collaborators in Michigan, have shown that it is possible to integrate simple logic circuits, actuators and structural elements into a single micro‑robotic body that can think, move and even heal minor damage. I see the reported cost, just one penny per unit, as a crucial part of the story, because it transforms these devices from rare lab artifacts into components that could be manufactured by the million and deployed like smart dust.

Descriptions of these systems emphasize that the robot, shown on a fingertip for scale, can move like a school of fish when many units operate together, coordinating their motion through shared responses to light or other stimuli. That behavior, combined with the one‑penny price point, is why analysts describe them as the world’s tiniest robots that can think, move and heal, all for just one penny, a characterization grounded in reports that Read Time, Scientists, University of Pennsylvania have built robots that can move like a school of fish while costing only a cent each.

From lab curiosity to practical platform

As I weigh all of these details together, from the About 0.3 M body length to the ability to Balance on the Ridge of a fingertip, it is clear that microrobotics has crossed a threshold. These are no longer isolated proof‑of‑concept devices that require bulky external rigs, they are coherent platforms that combine sensing, actuation and basic computation at a scale where a single robot can hide in the groove of a fingerprint. That shift opens the door to medical tools that travel through the bloodstream, environmental monitors that drift through air or water and industrial inspectors that crawl into microscopic cracks, all without ever being seen.

The fact that University Researchers Debut Tiny Programmable Robots from Michigan and Pennsylvania, that Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the Universi have created autonomous robots smaller than salt, that By Carly Cassella and Marc have shown a microrobot balancing on a fingerprint, that Light Powers the World, Smallest Programmable Robot, About, Millimeters Long, Learn to operate at 0.3 M, that They swim, think, and even respond to their environment as autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller, that the World, Smallest Programmable Autonomous Robots, Small Enough, Balance, Ridge of a fingertip are built at the scale of cells and 50 micrometers thick, and that Read Time, Scientists, University of Pennsylvania have demonstrated robots that can think, move and heal for just one penny, all point to the same conclusion: the age of nearly invisible, programmable robots has arrived, and it is likely to reshape how I think about machines, autonomy and the very boundaries of what counts as a robot.

More from MorningOverview