Reaching Alpha Centauri within a single human lifetime has long sounded like science fiction, yet a new generation of nuclear pulse concepts is forcing that timeline into serious discussion. The idea is starkly ambitious: a “nuked‑pulse” rocket that rides a series of controlled nuclear blasts or fusion pulses to a significant fraction of light speed, fast enough to cross the 4.37 light‑year gulf in roughly 44 years. Instead of a fragile sail or a chemical booster, this approach leans on the most energy‑dense technology humanity has ever built and asks whether we are finally ready to point it at the stars.

As I look across current propulsion research, from near‑term nuclear thermal test flights to radical pulsed plasma engines, the pieces of such a mission are starting to look less like fantasy and more like an extreme extrapolation of work already underway. The question is no longer whether physics allows a 44‑year trip to Alpha Centauri, but whether politics, engineering risk and planetary safety will ever line up behind a rocket that quite literally detonates its way into interstellar space.

From Cold War fever dream to interstellar thought experiment

The basic template for a nuked‑pulse starship was laid down in the late 1950s with Project Orion, a program that proposed pushing a massive spacecraft by ejecting nuclear explosives behind a giant metal plate and letting the blast waves do the work. In the canonical design, the vehicle would ride a sequence of hundreds or thousands of small nuclear charges, each one vaporizing propellant and slamming into a shock‑absorbing “pusher plate” to generate thrust, a concept that detailed studies of Project Orion treated as technically plausible even at very large scales. Advocates argued that, in principle, such a system could reach a few percent of light speed, enough to cross interstellar distances in centuries rather than millennia, if the political and environmental costs of detonating nuclear devices in space could be accepted.

That political barrier proved insurmountable, and Orion was shelved as nuclear test ban treaties took hold, but the underlying physics never went away. Later analyses of nuclear pulse propulsion, including work that explored how saving fuel for slowing down effectively halves the maximum cruise speed, kept refining the trade‑offs between payload mass, bomb yield and achievable velocity within the same basic framework that the original idea of nuclear pulse rockets had introduced. In other words, the Orion concept was less a dead end than a starting point for a family of designs that trade explosive pulses for unprecedented exhaust velocity.

Why 44 years to Alpha Centauri is even on the table

To understand how a 44‑year trip becomes plausible, it helps to compare it with other interstellar proposals that already push the limits of known technology. One widely discussed concept envisions featherweight spacecraft, each no heavier than a typical cell phone, being pushed from Earth orbit toward Alpha Centauri at about 20 percent of light speed by a powerful ground‑based laser, a scenario in which From Earth orbit the journey time drops to roughly 20 years but the payload is measured in grams. A nuked‑pulse rocket, by contrast, trades that extreme lightness for a much heavier, shielded vehicle that might “only” reach perhaps 10 percent of light speed, stretching the cruise time to around 44 years but allowing a far more capable probe or even a crewed habitat.

There is also a growing body of work on how small, gram‑scale probes might be our first emissaries to another star, including analyses that break down what it would take to send a 1‑gram craft to Alpha Centauri in about 20 years and how close current materials and laser systems are to that goal, as explored in detailed explainers such as Alpha Centauri in 20 years. When I set those concepts next to nuclear pulse designs, the trade space becomes clear: lasers and sails favor tiny payloads and very high speeds, while nuclear pulses favor bulkier, more robust spacecraft at somewhat lower fractions of light speed. A 44‑year timeline sits in the middle, long by human standards but short enough that mission designers can imagine a single generation seeing launch, cruise and arrival.

Project Daedalus and the fusion pulse blueprint

If Orion was the first draft of a nuclear pulse starship, Project Daedalus was the more refined second pass that swapped fission bombs for fusion pellets. In the 1970s, Daedalus designers studied a two‑stage vehicle that would use inertial confinement fusion, firing pellets of fuel into a reaction chamber and igniting them with electron beams to create a series of controlled micro‑explosions, a scheme that later analyses of Project Daedalus describe as a baseline for many post‑Orion designs. The goal was to reach about 12 percent of light speed and cover the distance to Barnard’s Star in roughly 50 years, with the first stage burning for a couple of years and the second for a few more before a long coasting phase.

What makes Daedalus so relevant to a 44‑year Alpha Centauri mission is not just its target speed but its detailed engineering assumptions about pellet rate, engine mass and fuel load, which remain among the most thoroughly worked out numbers for any fusion pulse concept. Later work on nuclear pulse propulsion has built on that foundation, noting that newer designs using inertial confinement fusion could, in principle, be adapted as a rocket engine that trades some performance for greater practicality, a point underscored in analyses that explicitly describe how Newer designs using inertial confinement fusion have become the baseline for post‑Orion thinking. If Daedalus could aim for 12 percent of light speed with 1970s assumptions, a more advanced fusion pulse system nudged toward 10 percent for Alpha Centauri in 44 years looks like a conservative extrapolation rather than a wild leap.

How a nuked‑pulse starship would actually work

At its core, a nuked‑pulse rocket is brutally simple: it throws mass out the back at extreme speed and lets conservation of momentum do the rest. In the classic Orion architecture, that mass is the debris from nuclear explosives detonated behind a pusher plate, with shock absorbers smoothing the otherwise violent ride into a steady acceleration that a crew or delicate instruments could survive, a configuration that detailed diagrams of the Orion spacecraft key components lay out in surprising specificity. Fusion pulse variants replace discrete bombs with a rapid‑fire stream of pellets, but the principle is the same: each pulse adds a small increment of velocity, and over months or years those increments add up to a significant fraction of light speed.

In practice, the engineering is anything but simple. The pusher plate must survive repeated blasts without eroding away, the shock absorbers must convert impulsive forces into manageable acceleration, and the timing of each pulse must be synchronized with the vehicle’s motion to maintain efficiency. Discussions among technically minded enthusiasts, including threads that note how scaling up nuclear bombs is relatively straightforward while making them work effectively at a small scale is much more difficult, such as the Real Engineering Orion Drive debate, highlight just how fine the line is between a workable pulse unit and a device that wastes most of its energy. For a 44‑year Alpha Centauri mission, those challenges would be compounded by the need for near‑perfect reliability over millions of pulses, with no opportunity for repair once the ship has left the Solar System.

Near‑term nuclear rockets are already being built

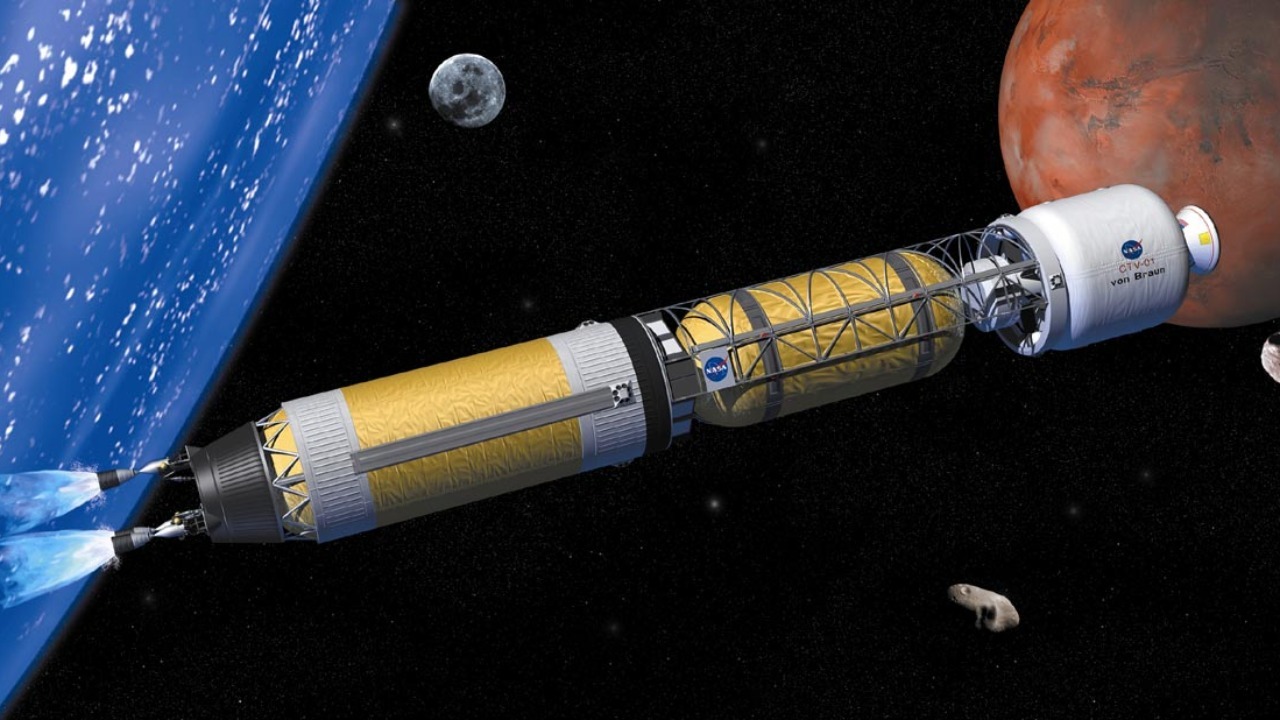

While a true interstellar pulse ship remains hypothetical, the political and technical groundwork for nuclear propulsion is being laid in Earth orbit. NASA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency are collaborating on a nuclear thermal rocket known as DRACO, with plans to launch a demonstration vehicle to orbit by early 2026, a milestone that program briefings describe as a joint effort in which Share this article level attention has been paid to how such a reactor can safely operate in space. Nuclear thermal propulsion is not the same as nuclear pulse, but it shares the core idea of using a compact reactor to dramatically increase exhaust velocity compared with chemical rockets.

In parallel, the United States is pursuing broader nuclear spacecraft capabilities, with plans to put a nuclear‑powered vehicle in orbit by 2026 that rely on a compact reactor to heat propellant and provide both thrust and electrical power, a vision in which program documents explicitly credit Credit NASA for pushing nuclear thermal propulsion as a way to cut travel times to Mars. These efforts are not about detonating bombs behind a plate, but they are forcing regulators, engineers and the public to confront the realities of launching nuclear hardware, managing reactor safety and building the industrial base for high‑temperature fuels. From my perspective, every successful nuclear thermal test makes a future conversation about more aggressive nuclear pulse systems slightly less abstract.

Pulsed plasma rockets and the bridge to fusion pulses

Alongside fission reactors, a new class of pulsed plasma concepts is emerging that looks like a conceptual bridge between today’s electric thrusters and tomorrow’s fusion pulse engines. One NASA‑funded design, developed by Arizona‑based Howe Industries, envisions a propulsion system that uses pulses of superheated plasma to generate thrust with remarkably high fuel efficiency, a configuration in which Arizona Howe Industries is explicitly cited as working on a potentially groundbreaking system for fast Mars transfers. Instead of a continuous burn, the engine fires discrete bursts, each one imparting a small kick, much like a gentler, non‑nuclear cousin of a pulse rocket.

Another concept, sometimes referred to as a Pulsed Plasma Rocket or PPR, has been described as a way to get crews to Mars and back in about two months by using rapid pulses of superheated plasma that can be throttled up for acceleration and then down to brake at the destination, a profile in which technical explainers emphasize How a rocket could get to Mars and back in dramatically shorter times. A separate NASA‑supported study of a pulsed plasma concept has been framed as a way to reach high velocities while still being efficient enough to operate within the inner Solar System, with outreach materials that even instruct viewers to Tap to unmute and note that Tap to unmute if their browser cannot play the explanatory video. When I connect these dots, I see a clear pattern: engineers are getting comfortable with pulsed operation, high‑energy plasmas and long‑duration reliability, all of which are prerequisites for any future fusion pulse starship.

NASA’s own Alpha Centauri ambitions set a benchmark

Even within official space agencies, interstellar probes are no longer taboo topics. In December 2017, NASA released a mission concept that envisioned launching an interstellar probe in 2069 to search for signs of life in the Alpha Centauri system, a study that explicitly framed the target as a spacecraft capable of reaching at least 10 percent of the speed of light, as summarized in documentation of the In December NASA mission concept. That speed is almost exactly what a 44‑year cruise to Alpha Centauri would require, once acceleration and deceleration phases are accounted for, which means the nuked‑pulse scenario is not operating outside the velocity envelope that mainstream planners are already using as a benchmark.

What NASA’s concept does not do is commit to a specific propulsion technology, instead leaving the door open to advanced fusion, antimatter or other high‑energy systems that might mature over the coming decades. From my vantage point, that agnosticism is both a challenge and an opportunity for nuclear pulse advocates. On one hand, it means a nuked‑pulse rocket must compete with alternatives that promise similar speeds without the political baggage of nuclear explosives. On the other, it signals that if any technology can credibly deliver 10 percent of light speed with a reasonable payload, whether through inertial confinement fusion or some hybrid plasma system, it will be taken seriously as a candidate for the first true interstellar mission.

Community debates and the legacy of the Orion Proj

Outside formal studies, online communities have kept the Orion lineage alive by stress‑testing its assumptions and imagining alternate histories. In physics forums, contributors often revisit the question of how fast a realistic spaceship could go, with many pointing out that the idea of nuclear pulse rockets has been around since the 1950s and that there are several variations, the most well known being the classic Orion configuration that uses a series of nuclear explosions behind a spacecraft to push it forward, as summarized in discussions like realistically how fast a ship could go. These debates often converge on the same conclusion: nuclear pulse systems are among the few concepts that can, in principle, reach interstellar cruise speeds with known physics, but they come with daunting engineering and ethical hurdles.

History‑minded threads go further, asking what might have happened if the Orion Proj had never been cancelled and had instead matured into an operational technology. In one such scenario, enthusiasts argue that a fully developed Orion Proj could have made travel to places like alpha/Proxima centauri a possibility, treating the cancellation as a fork in the road that diverted humanity away from a nuclear‑driven spacefaring future, a line of thought captured in speculative analyses of what if the Orion Proj had continued. I find these conversations valuable not because they prove anything about feasibility, but because they map out the cultural and political terrain that any future nuked‑pulse proposal would have to navigate.

The hard limits: deceleration, safety and politics

Even if engineers could build a nuked‑pulse engine that reliably accelerates a starship to 10 percent of light speed, the mission design problem is only half solved. To arrive at Alpha Centauri in any useful state, the spacecraft must also slow down, which means reserving a significant fraction of its pulse units for deceleration or relying on external methods such as a magnetic sail that interacts with the interstellar medium, a trade‑off that detailed analyses of using a magnetic sail have shown can effectively halve the maximum speed if fuel is split between speeding up and slowing down. For a 44‑year timeline, that means either accepting a one‑way flyby at full speed or designing a more complex mission that trades cruise time for the ability to enter orbit around a target star.

Then there are the safety and political constraints that doomed Orion the first time around. Detonating nuclear devices in space raises questions about fallout, treaty compliance and weaponization that go far beyond the technical merits of the engine. Even non‑explosive nuclear systems, such as the reactors being developed for near‑term Mars missions, have had to navigate public concerns, with outreach materials that explicitly invite viewers to Learn more and reassure them that Learn more about how such hardware will be tested in orbit by early 2026. Scaling up from a single reactor to thousands or millions of nuclear pulses would require not just new engineering, but a new global consensus about what kinds of nuclear activity are acceptable beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Why the 44‑year dream still matters

For all those obstacles, I find the 44‑year Alpha Centauri scenario valuable as a way to sharpen our thinking about what it would really take to become an interstellar species. It forces mission planners to confront concrete numbers for speed, fuel mass and reliability, rather than hand‑waving about “future technology,” and it ties those numbers back to real programs like DRACO, the pulsed plasma work at Howe Industries and the official NASA studies that already treat 10 percent of light speed as a serious target. It also connects to a broader cultural conversation, from technical forums dissecting the Orion drive to speculative histories of the Orion Proj, about whether humanity is willing to accept the risks that come with wielding nuclear energy at such unprecedented scales.

In that sense, the nuked‑pulse rocket is less a single design than a thought experiment that spans decades of research, from the early optimism of Orion to the more cautious, incremental steps of today’s nuclear thermal and pulsed plasma projects. Whether or not a specific 44‑year mission ever flies, the work being done now on nuclear propulsion, high‑energy plasmas and interstellar mission concepts is steadily eroding the gap between what is technically conceivable and what is politically and economically possible. If a future generation does decide to light off a sequence of nuclear pulses and aim for Alpha Centauri, it will be building on a foundation that is already, quietly, taking shape.

More from MorningOverview