A starship driven by a captive black hole sounds like pure science fiction, yet the underlying physics is brutally literal. A tiny, artificial singularity would convert mass into energy with an efficiency no chemical or nuclear rocket can touch, turning Hawking radiation into thrust and waste heat into a design problem as serious as navigation. If engineers ever build such a machine, it will not look like a sleek movie cruiser, but like a flying power plant wrapped around a weaponized point of gravity.

To picture a real black hole starship, I have to start from what the equations demand: a small enough black hole to radiate intensely, a long enough lifespan to cross interstellar distances, and a structure that can both feed and survive it. From there, the ship’s silhouette, its engines, and even its crew quarters fall out of the constraints, much as today’s stainless steel launch systems are shaped by propellant tanks and reentry loads rather than aesthetics.

The heart of the ship: a manufactured micro black hole

Any realistic design begins with the engine, and in this case the engine is a microscopic black hole created on purpose. The concept, often called a kugelblitz, imagines focusing an immense burst of energy with a laser until it collapses into a singularity with a mass comparable to a starship, small enough to radiate strongly but heavy enough to avoid evaporating in a flash. The crux of the idea involves using a laser to form a micro black hole, and that laser pulse must be so intense that it effectively compresses light itself into a gravitational trap, as described in proposals that treat the black hole as an onboard power source rather than a distant hazard, a scenario outlined in detail in work linked through Nov.

Once formed, this artificial singularity would sit at the geometric center of the vessel, not in a traditional engine bell but inside a heavily shielded chamber that functions more like a reactor core. To create useful amounts of energy a black hole has to be relatively small, since tiny ones radiate far more intensely than the supermassive giants that form from the implosion of stars, and that requirement drives the rest of the architecture around it, as explored in analyses of how compact black holes outshine very big ones in power density, such as the work discussed in Mar. The ship’s primary structural ring, radiation shielding, and magnetic fields would all be sized to keep this tiny but furious object caged and aligned with the thrust axis.

How a black hole drive actually pushes a starship

Turning raw Hawking radiation into motion is the next design challenge, and it dictates the ship’s most distinctive external feature. The black hole would spray out high energy particles and photons in every direction, so to harness that energy and propel a starship, engineers would place it at the focus of a parabolic mirror made not of glass but of an electron gas, a kind of electromagnetic reflector that can survive the onslaught. This mirror would redirect a large fraction of the emitted radiation into a tight beam, producing thrust in the opposite direction and giving the vessel a characteristic dish or cone structure behind the core, a configuration described in detail in concepts for a black hole drive.

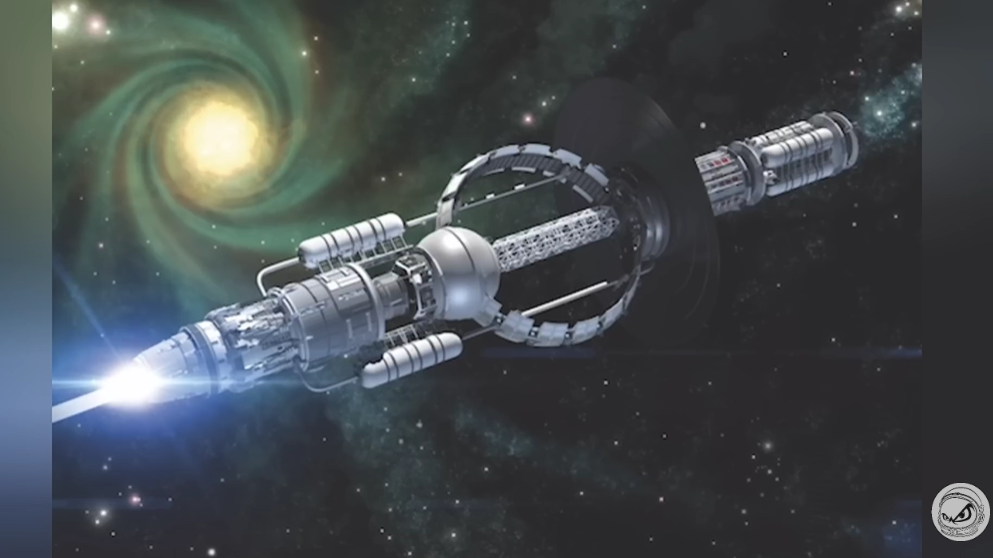

From a distance, that means a real black hole starship would look less like a rocket and more like a gigantic, glowing searchlight with a compact, shielded hub at its focal point. The thrust structure would likely be a lattice of high temperature materials and magnetic coils, shaping and collimating the radiation plume while allowing waste heat to escape. Because the black hole’s output is fixed by its mass, the ship’s acceleration profile and maximum speed are set by the balance between the mirror’s efficiency and the mass it has to push, a tradeoff that has been quantified in studies of how such a drive could reach a reasonable fraction of light speed if the geometry is optimized, as summarized in technical discussions of a black hole starship.

Feeding the singularity and managing its lifespan

Because a small black hole radiates away its mass, the ship must constantly feed it, and that requirement shapes the internal layout like a refinery wrapped around a furnace. Tanks of propellant, probably ordinary matter rather than exotic fuel, would be routed through particle accelerators or magnetic funnels that inject mass directly into the event horizon, keeping the black hole’s mass and lifespan within a narrow operating window. If the crew wants more thrust, they let the hole shrink and brighten; if they want endurance, they feed it more aggressively to slow the evaporation, a balancing act that underpins calculations of how long such an engine can run before it burns itself out, as explored in models of a long enough lifespan for interstellar travel.

However, such a scenario assumes that 100 percent of the energy emitted by the black hole is used for the acceleration of the spacecraft, which is wildly optimistic once real hardware is involved. In practice, large fractions of the output would be lost as unusable radiation or dumped as heat into radiators, and the ship would need additional mass reserves simply to sustain the black hole over the course of the journey, a constraint that has been highlighted in critiques of idealized performance estimates, including the reminder that, However, even small inefficiencies quickly erode the theoretical advantages, as discussed in analyses of a black hole propelled.

Radiation shields, crew habitat, and the human footprint

The human part of the vessel would be an afterthought compared with the engine, tucked as far as possible from the singularity and its radiation plume. I would expect a long truss extending forward from the core, ending in a relatively small, heavily shielded habitat module that rides ahead of the blast like the tip of a spear. The living quarters would be wrapped in layers of dense material and magnetic shielding, with most of the ship’s mass concentrated between the crew and the engine to soak up stray particles, a layout that echoes how current long range concepts place people at the end of a boom to minimize exposure from reactors and exhaust, and that would be even more critical when the power source is a kugelblitz as described in work on Fast evolving black hole ideas.

Inside that forward module, the design language would borrow from high performance spacecraft already on the drawing board, with modular decks, integrated life support, and multi use spaces that can be reconfigured for long missions. The way current heavy lift vehicles like Starship stack propellant tanks and pressurized volumes shows how much of a modern spacecraft is just structure wrapped around fuel, and a black hole vessel would be similar, except that the fuel is both propellant and engine feedstock. Even concepts for turning landed vehicles into permanent habitats, such as plans to use stacked ships as part of a Lunar Base Alpha supported by an anchored winch system described in Jan, hint at how future crews might treat their interstellar ship as both transport and long term home once it reaches another star.

From speculative physics to engineering reality

All of this rests on a foundation of theory that began with classical relativity and was transformed by quantum insights. Fast forward 19 years from the first modern black hole solutions to the work of Stephen Hawking, who realized that quantum mechanical effects near a black hole’s event horizon would cause it to emit radiation and slowly evaporate, turning what had been thought of as perfect sinks into potential power sources. That insight is what makes a black hole engine conceivable at all, since it provides a way to tap the mass of the singularity itself rather than relying only on infalling matter, a shift in perspective that underlies modern discussions of using Hawking radiation to drive interstellar craft, as detailed in treatments of Stephen Hawking and black hole power.

Yet the gap between equations and hardware is enormous, and a real black hole starship would be a monument to that difficulty as much as to human ambition. The energy required to create a kugelblitz, the precision needed to confine it, and the materials that could survive near its radiation field are all far beyond current technology, even as advanced launch systems and off world habitat concepts inch closer to reality. The vision of a starship wrapped around a captive singularity, with a parabolic electron gas mirror flaring behind it and a slender, shielded habitat riding far ahead, is not a prediction but a sketch of what the laws of physics seem to allow, grounded in the constraints explored in studies of engineers of the and the brutal efficiencies of gravity itself.

More from Morning Overview