The latest generation of experimental aircraft is no longer chasing raw speed alone, it is trying to change how the air itself behaves around a flying machine. From quiet supersonic jets to flexible wings and digital control surfaces, engineers are using these testbeds to challenge assumptions that have guided aviation for decades. If the most ambitious of these projects succeed, the rules that have defined how fast, how efficiently and where we can fly may look very different within a single generation.

At the center of that shift is a new class of X-planes and defense prototypes that treat the entire airframe as a controllable system rather than a fixed shape. By blending advanced aerodynamics with evolving regulations and a more permissive test environment, these aircraft are probing the limits of noise, structural flexibility and safety margins in ways that were not possible even a few years ago.

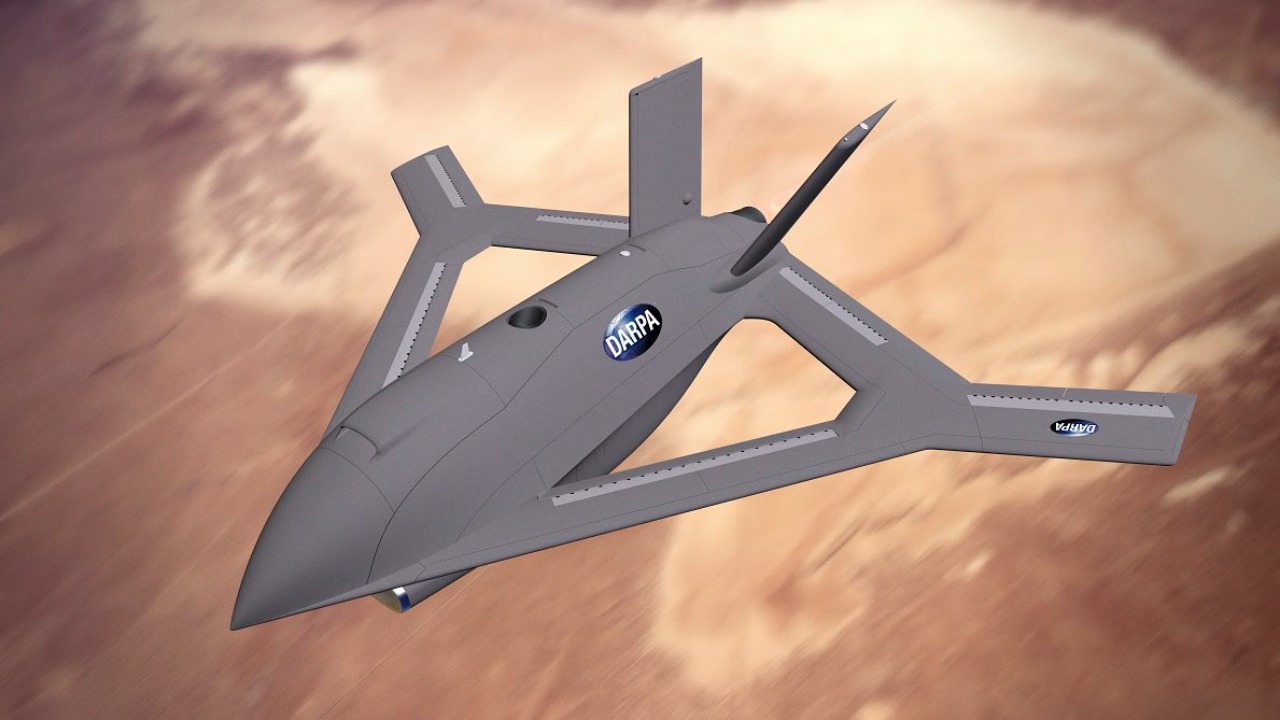

The X-65 and the end of moving control surfaces

One of the most radical concepts now in flight test is the X-65, an experimental jet that replaces traditional flaps, ailerons and rudders with a morphing wing and embedded actuators. Instead of hinged panels deflecting into the airstream, the aircraft subtly reshapes its lifting surfaces, using internal mechanisms to twist and flex the structure so that the airflow itself is redirected. That approach promises smoother handling, fewer drag-inducing gaps and joints, and a cleaner airframe that could be easier to maintain over a long service life.

The X-65 has been described as being Developed under DARPA oversight, which signals how strategically important this technology is for both military and civilian aviation. By proving that a jet can maneuver and remain stable without the familiar moving surfaces, the program is testing whether future airliners and combat aircraft can trade mechanical complexity for smart structures and software. If the concept scales, it could reshape how designers think about redundancy, damage tolerance and even stealth, since there are fewer edges and gaps to reflect radar energy.

Quiet supersonic flight and the X-59’s “gentle thump”

While the X-65 challenges how aircraft steer, another experimental jet is trying to change what supersonic flight sounds like on the ground. The X-59 is a slender, needle-nosed aircraft built to demonstrate that a carefully sculpted fuselage and engine integration can turn the classic sonic boom into something closer to a muted thud. Instead of chasing speed records, the program is focused on acoustic signatures, because the barrier to routine supersonic travel over land has always been noise, not physics.

Engineers working on the X-59 have framed the goal as proving that the real obstacle is a regulatory wall, not speed records, and that a quieter shockwave could justify new rules for supersonic routes. The aircraft’s long nose, offset cockpit and carefully faired engine inlets are all tuned to spread out pressure waves so they reach communities below as a “gentle thump” instead of a window-rattling crack. If flight tests confirm that prediction, the data could underpin a new standard for overland supersonic noise and reopen a market that has been effectively closed since the original Concorde era.

NASA’s X-59 and the first quiet boom in the real sky

The theory behind quiet supersonic flight has now moved from wind tunnels to the real sky. Earlier this year, NASA’s X-59 experimental jet completed its first supersonic run over Cali, demonstrating that the aircraft can break the sound barrier while keeping its noise footprint within the predicted range. The flight was a crucial step, not just for the engineering team, but for regulators who will rely on real-world acoustic data rather than simulations when they consider new rules.

NASA has described the X-59 as their experimental aircraft that can break the sound barrier quietly, and the agency is now preparing a series of community overflights to measure how people perceive the sound. Those surveys will matter as much as the decibel readings, because any future standard will have to balance technical thresholds with public tolerance. If residents report that the thump is acceptable, it will strengthen the case for rewriting long standing bans on supersonic travel over populated areas.

From unveiling to policy testbed: how the X-59 fits the bigger picture

The X-59 is not just a one-off science project, it is a deliberate bridge between experimental hardware and future commercial designs. When the aircraft was first shown in public, engineers emphasized that it had been “Meticulously engineered” to produce a controlled acoustic footprint rather than chase maximum Mach numbers. The cockpit relies on external cameras and a 4K monitor instead of a traditional forward window, a choice that frees the nose to be shaped purely for aerodynamics and noise control.

That design philosophy is meant to feed directly into how regulators and manufacturers think about the next generation of supersonic transports. The pilot of NASA’s X-59 is flying a machine that is explicitly intended to support civilian supersonic flights over land, not just military missions or record attempts. If the program can show that a carefully shaped airframe and advanced displays can coexist safely, it will give commercial designers more freedom to prioritize external aerodynamics without sacrificing situational awareness in the cockpit.

Longer, thinner wings and the rise of flexible structures

Quiet booms are only one part of the experimental landscape. Another major push is happening at subsonic speeds, where engineers are stretching wings to new aspect ratios to cut fuel burn and smooth out turbulence. In the United States, NASA and Boeing are flight testing longer, thinner wings that promise a more efficient cruise and a gentler ride, but that also introduce new structural challenges as the wings flex and twist under load.

These high aspect ratio designs rely on active control systems to manage what specialists call the aeroelastic response, the way a wing bends and vibrates in flight. When you have a very slender wing, you cannot simply make it stiffer without adding weight, so the solution is to sense and adjust its behavior in real time. The current test program is exploring how to deliver a smoother ride while saving fuel, a combination that airlines are eager to see mature into a certified product.

NASA’s X-66A and the future of efficient airliners

To turn these aerodynamic ideas into something closer to a workhorse, NASA has launched the X-66A, described as its newest X-plane and a next generation experimental aircraft that “will help shape the future of aviation.” The project is focused on sustainable transport, using a modified airliner platform to test advanced wing structures, propulsion integration and systems that could cut emissions and operating costs for large fleets. It is less about exotic shapes and more about proving that incremental innovations can add up to a step change in performance.

By flying a full scale demonstrator, NASA is giving manufacturers a real world reference for how new materials, control laws and engine placements behave outside the lab. The agency has been explicit that the X-66A will help shape the future by de-risking technologies that airlines might otherwise hesitate to adopt. If the program can validate significant fuel savings without compromising reliability, it will strengthen the business case for more radical wing designs and hybrid propulsion concepts on future commercial types.

Regulators move: MOSAIC, supersonic rules and Trump’s order

None of these experimental aircraft can change aviation on their own, they need regulators to update the rulebook. In general aviation, that process has already started with the Modernization of Special Airworthiness Certification, or MOSAIC, which expands what light aircraft can do and how they can be certified. After more than a decade of collaborative work between the Experimental Aircraft Association, the EAA, the FAA and numerous industry stakeholders, MOSAIC has become a reality and is now reshaping how small manufacturers bring new designs to market.

Manufacturers have described the new framework as a major win, and one industry voice, identified as Nov, has publicly welcomed the MOSAIC rules as a long awaited modernization. At the same time, supersonic policy is shifting at the national level. An order from the US administration under President Donald Trump directed the FAA to establish an interim noise based certification standard and repeal other restrictions, instructing the agency to create a standard for supersonic aircraft noise certification that could eventually allow new designs to operate more freely. That directive, detailed in an order to the FAA, is one reason quiet boom demonstrators like the X-59 now have a clearer regulatory target.

Industry testbeds: Boom Supersonic and XB-1

While government X-planes explore the physics and policy edges, private companies are building their own experimental fleets to prove that a new generation of supersonic airliners can be commercially viable. Boom Supersonic has developed a working “baby boom” XB-1 aircraft as a technology demonstrator, using it to test aerodynamic concepts, materials and propulsion strategies that could feed into a larger passenger jet. The company has also highlighted its use of renewable biofuel to limit emissions, positioning speed as compatible with climate goals rather than opposed to them.

Regulators have given these efforts more room to operate by allowing supersonic aircraft to be tested over land under controlled conditions, rather than forcing every high speed run offshore. Boom has said its XB-1 will not need to ask for permission for each test, a shift that reflects the FAA’s evolving stance on experimental supersonic programs. The broader policy context includes a federal order that cleared the way for supersonic flight to return to the United States after a half century ban, with Boom Supersonic cited as having broken the sound barrier sans a boom earlier this year, a milestone that aligns closely with NASA’s quiet boom ambitions.

Safety margins, human factors and the invisible rules of design

Behind every experimental aircraft is a dense web of safety assumptions that rarely make headlines but quietly shape what is possible. Commercial aircraft designers must engineer within the bounds called for in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulation, which defines everything from structural loads to performance margins. Those rules are written with conventional airframes in mind, and they assume a certain relationship between pilot inputs, control surface movements and the resulting aircraft response.

As morphing wings, flexible structures and software heavy control systems become more common, those assumptions are being tested. Researchers have warned that “off book” flight speeds and behaviors can emerge when pilots push aircraft beyond the conditions described in the certified flight manual upon which they depend. A detailed analysis of these issues notes that Commercial aircraft designers must account for human factors as much as structural ones, especially when new technologies blur the line between normal and edge of envelope operations. Experimental programs like the X-65 are therefore as much about validating control laws and pilot interfaces as they are about proving exotic hardware.

Why this wave of experiments really could rewrite flight

When I look across these programs, from the X-65 and X-59 to the X-66A and XB-1, what stands out is how coordinated they have become. Quiet supersonic demonstrators are feeding data into evolving noise standards, flexible wing testbeds are informing efficiency targets, and regulatory reforms like MOSAIC are giving smaller innovators a clearer path to certification. This is not the fragmented experimentation of earlier eras, it is a loosely aligned ecosystem that is trying to move the entire industry’s performance frontier outward.

The stakes are captured neatly in a recent explainer that framed one of these demonstrators as an aircraft that might rewrite the rules of flight, a phrase that reflects both the technical ambition and the regulatory implications. That piece, introduced under the banner “Why this experimental aircraft might rewrite the rules of flight,” underscores how each successful test can ripple outward into new standards, new commercial products and new expectations from passengers. If the current wave of experiments delivers on even a fraction of its promise, future travelers may take for granted quiet supersonic hops, ultra efficient long haul wings and airframes that flex and adapt in ways that today still feel like science fiction.

The X-65’s broader implications for military and civil aviation

The X-65 in particular has implications that reach far beyond its own test envelope. By eliminating conventional moving control surfaces, it points toward a generation of aircraft that could be harder to detect, easier to maintain and more resilient to battle damage or component failures. For military planners, a jet that can keep flying even if parts of its wing are compromised, because the remaining structure can be reconfigured on the fly, is an attractive prospect. For civil operators, fewer hydraulic actuators and hinges could translate into lower maintenance costs and higher dispatch reliability.

The program’s backers have emphasized that it is being Developed under DARPA oversight precisely because it straddles this civil military boundary. If the core technologies prove out, they could migrate into stealthier drones, agile fighters and eventually high efficiency airliners that use subtle wing warping instead of large flaps for takeoff and landing. The fact that the last time anyone tried to bring supersonic travel back at scale it ran into a wall of cost and noise complaints, a reality highlighted in another analysis of how hard it is to bring back supersonic, is a reminder that only a combination of technical and regulatory innovation will make this new wave stick.

More from Morning Overview