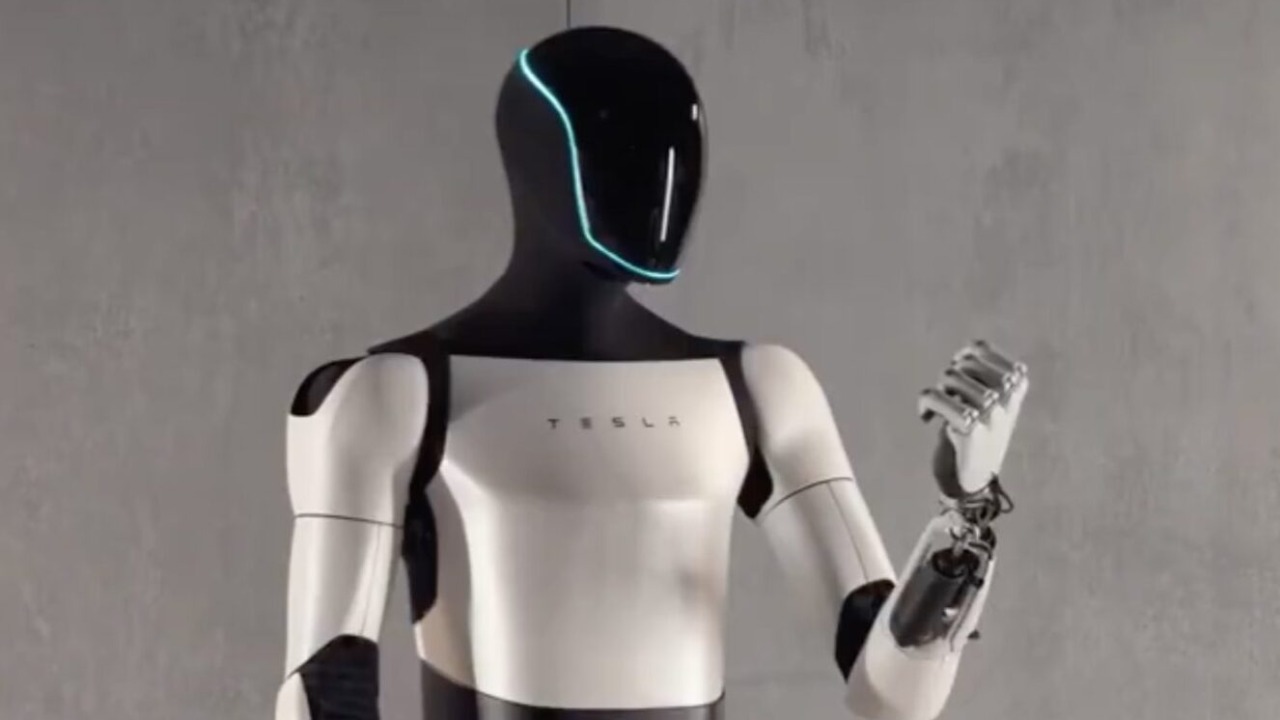

I keep hearing the same question whenever the Tesla Bot shows up in my feed: is Elon Musk really trying to build a friendly household helper, or is something much bigger going on behind the scenes? When I look past the stage demos and marketing sizzle, the real reason he is pushing so hard on humanoid robots looks less like a side project and more like an attempt to redefine what Tesla is for the next several decades.

To understand why, I have to follow the money, the AI strategy, and the way Musk talks about the future of work and human relevance. Put together, they point to a single, uncomfortable conclusion: the Tesla Bot is not just a gadget, it is Musk’s bet that the most valuable product Tesla will ever sell is labor itself.

From Car Company To Labor Company

When I trace Musk’s public comments, the first thing that jumps out is how openly he frames Optimus—the official name for the Tesla Bot—as central to Tesla’s valuation. In one interview, he said that about 80 percent of Tesla’s long‑term value could eventually come from its robots rather than its vehicles, a staggering claim for a company still known primarily for the Model 3 and Model Y, and one that is spelled out in detail in an analysis of how Optimus could dominate Tesla’s future company value. If I take that statement seriously, the Tesla Bot stops looking like a flashy prototype and starts looking like the core of a new business model built around selling physical labor as a service.

That shift lines up with how Tesla now presents itself in its own AI materials. On its official AI page, the company describes a vertically integrated stack of neural networks, custom chips, and large‑scale training infrastructure originally built for Autopilot and Full Self‑Driving, and then explicitly extends that same stack to “general purpose, bi‑pedal, autonomous humanoid robots” under the Optimus banner Tesla AI. In other words, the company is telling investors and customers that the same software that interprets the world for a car will soon interpret the world for a robot worker, turning Tesla from a carmaker into a platform for embodied AI that can be dropped into factories, warehouses, and eventually homes.

Why A Humanoid Robot At All?

Once I accept that Tesla wants to sell labor, the next question is why Musk insists on a humanoid form instead of a fleet of specialized machines. In an essay unpacking the Optimus design, he argues that a human‑shaped robot can immediately plug into the world we have already built—stairs, door handles, forklifts, and factory tools—without forcing companies to redesign their infrastructure around new hardware Optimus design. That logic is simple but powerful: if the robot can walk where a person walks and grab what a person grabs, then every workplace becomes a potential market without expensive retrofits.

I see the same rationale echoed in technical presentations where Tesla engineers show Optimus using the same vision‑based perception stack as its cars, but applied to arms, hands, and legs instead of wheels. In one detailed breakdown of the project, they walk through how the robot’s cameras, actuators, and control loops are tuned to mimic human motion and balance, emphasizing that the goal is not just mobility but the ability to perform “unsafe, repetitive, or boring” tasks currently handled by people engineering overview. The humanoid shape is not a sci‑fi flourish; it is the fastest way to drop AI into the labor market without rebuilding the physical world around it.

Reusing Tesla’s AI Stack Is The Real Play

Underneath the humanoid shell, the real reason Musk can even attempt this pivot is that Tesla has already spent years building an enormous AI engine for its cars. The company’s AI page lays out a pipeline of massive video datasets, custom Dojo training hardware, and end‑to‑end neural networks that interpret camera feeds to steer, accelerate, and brake in real time vision stack. From my perspective, the Tesla Bot is a way to amortize that investment: once you have a system that can understand roads, lanes, and pedestrians, you can retrain it to understand factory floors, shelves, and tools without starting from scratch.

That reuse shows up clearly in technical talks where Tesla staff demonstrate how the same perception and planning modules that guide a vehicle are being adapted to guide a bipedal robot through cluttered spaces, pick up objects, and avoid collisions shared autonomy. Instead of building a robot company from the ground up, Musk is effectively asking: what else can I do with a global fleet of camera‑equipped cars, a dedicated AI supercomputer, and a team already trained to ship safety‑critical machine learning systems at scale?

Economic Power: Selling “Universal” Labor

When Musk talks about Optimus driving 80 percent of Tesla’s value, he is really talking about the economics of labor. A car is sold once, but a robot that can work around the clock, be updated over the air, and be redeployed from one task to another starts to look like a subscription to physical work. In one widely shared segment on the Tesla Bot, commentators spell out how a humanoid robot could be leased to factories, logistics centers, and even hospitals, effectively turning Tesla into a provider of on‑demand labor that competes directly with human workers on cost and reliability labor economics. If that model works, the revenue potential dwarfs even the most optimistic projections for electric vehicle sales.

Some of the most candid speculation about this comes not from official presentations but from Tesla’s own fan and critic communities. In one detailed discussion thread, users argue that the “true intended purpose” of the Tesla Bot is to replace low‑wage, high‑turnover jobs in warehouses and manufacturing, with one commenter bluntly describing it as a way to “monetize every repetitive task on Earth” intended purpose. While that phrasing is opinion, it captures the logic behind Musk’s valuation claims: if a single robot can be sold or leased into multiple industries over its lifetime, the addressable market is not just transportation, it is the global labor pool.

Safety, Control, And The “Don’t Worry” Pitch

Whenever I dig into the ethics of humanoid robots, I find a sharp contrast between the fears people voice and the concerns experts highlight. In one analysis of the Tesla Bot, researchers argue that the biggest risks are not Hollywood‑style robot uprisings but more mundane issues like surveillance, data control, and the concentration of power in the hands of companies that own fleets of networked robots serious concerns. If Tesla controls the software, updates, and data flows for millions of Optimus units, it also controls a vast amount of information about how and where physical work happens, and who is being displaced.

Musk, for his part, tends to reassure audiences by emphasizing that the Tesla Bot is designed to be physically limited and easy to overpower, often joking that people should be able to “run away from it” if something goes wrong. In one presentation focused on the robot’s capabilities, he stresses that Optimus is meant to be “friendly” and that Tesla is building in safeguards to prevent misuse, while also showcasing increasingly sophisticated demos of the robot walking, lifting, and manipulating objects safety messaging. I notice a tension here: the more capable the robot becomes, the less reassuring those early jokes sound, especially when the business model depends on deploying it at massive scale.

How Musk Frames The Future Of Work

To Musk, the Tesla Bot is not just a product, it is a philosophical statement about where he thinks society is headed. In several long‑form conversations, he describes a future where robots handle most physical labor, leaving humans to focus on creativity, relationships, and high‑level decision‑making, often tying that vision to ideas like universal basic income as a buffer against job displacement future of work. When I listen closely, what he is really saying is that he expects large swaths of today’s workforce to become economically obsolete—and he wants Tesla to own the technology that makes that transition possible.

That framing shows up again in more technical interviews where he talks about Optimus as a “general purpose” worker that can be retrained via software updates, much like a smartphone app, to handle new tasks as industries evolve general purpose. In his telling, the Tesla Bot is a way to decouple economic growth from human labor hours: if you can scale robots faster than you can train and hire people, then productivity is limited only by how quickly you can manufacture and deploy hardware. It is an appealing story for investors, but a deeply unsettling one for anyone whose job fits the “unsafe, repetitive, or boring” description.

Marketing Hype Versus Technical Reality

Of course, none of this matters if Tesla cannot actually deliver a robot that works outside carefully staged demos. When I compare early stage presentations to more recent engineering updates, I see a clear progression: the first public reveal featured a person in a suit and a very limited prototype, while later videos show Optimus walking more smoothly, performing basic manipulation tasks, and using its hands with increasing dexterity capability demos. The gap between those clips and a robot that can reliably work an eight‑hour shift in a noisy factory is still enormous, but the direction of travel is obvious.

Critics often point out that other robotics companies have been working on humanoid platforms for years, and that Tesla is entering a field where balance, durability, and safety are brutally hard problems. In one skeptical breakdown of the project, analysts question whether Tesla’s camera‑only approach, inherited from its cars, will be robust enough for industrial environments where dust, lighting changes, and physical impacts are constant challenges technical skepticism. For now, I have to hold two truths at once: Musk’s long‑term vision for the Tesla Bot is extraordinarily ambitious, and the current hardware is still a work in progress that has not yet proven itself in real‑world deployments.

The Real Reason: Owning The Interface Between AI And The Physical World

When I put all of these threads together—the valuation claims, the reuse of Tesla’s AI stack, the humanoid design, the economic logic of selling labor, and the ethical debates—the real reason Elon Musk is developing the Tesla Bot comes into focus. He is not just trying to build a cool robot; he is trying to own the interface between advanced AI and the physical world, in the same way that smartphones became the interface between software and our daily lives. In one deep‑dive discussion of Optimus, commentators describe it as the “next platform” after the smartphone and the car, a device that could eventually be as ubiquitous as laptops are today next platform. If that vision pans out, whoever controls the dominant humanoid robot platform will wield enormous economic and political power.

That is why I see the Tesla Bot less as a side project and more as the centerpiece of Musk’s long‑term strategy for Tesla. The company’s own AI materials frame Optimus as a natural extension of its existing technology, while outside analyses warn that the real stakes are about labor, surveillance, and control rather than sci‑fi nightmares real stakes. For now, the robot is still learning to walk, grasp, and navigate. But the bet Musk is making is already clear: in a world where AI can think, the company that can also make it move will own the future of work.

More from MorningOverview