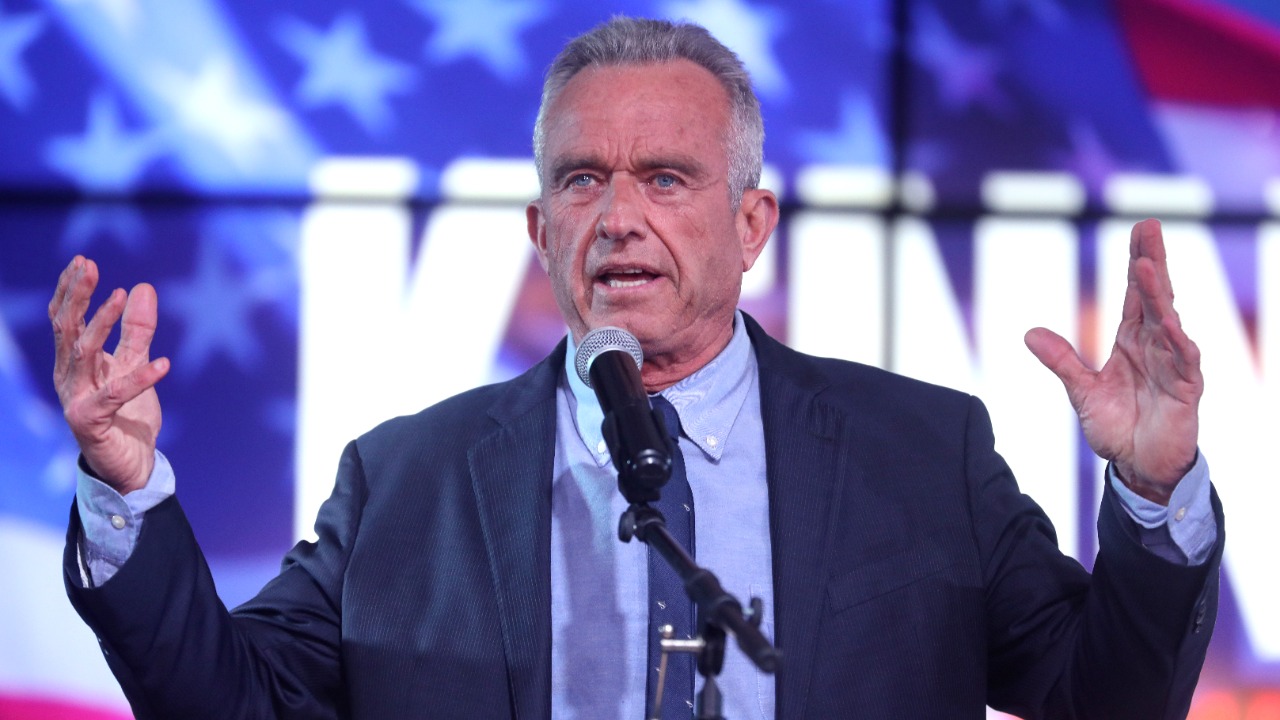

Federal health officials have abruptly narrowed the list of vaccines recommended for every American child, reshaping a schedule that had been stable for decades. At the center of the shift is Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr., whose skepticism of routine immunization has moved from the campaign trail into federal policy. I want to unpack which diseases he now says children do not need universal protection against, and what that means for families trying to keep kids safe.

The new guidance does not ban any shots, but it strips several major infections out of the default childhood lineup and leaves parents and doctors to sort out the gaps. That change, coming in a country with fragmented health care and deep misinformation about vaccines, raises very different risks than similar moves in smaller nations with stronger safety nets.

How RFK Jr. reshaped the childhood schedule

The United States had long recommended routine immunization against 17 diseases for all children, a schedule that public health experts credit with driving down hospitalizations and deaths. Earlier this year that framework was dismantled, with federal vaccine recommendations for pediatric patients cut from 17 to 11 in what one analysis called the most dramatic shift in public health practice in decades, a change reflected in new Federal guidance. I see that reduction as the policy expression of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s long‑standing argument that children are “overvaccinated,” even though the prior schedule had a decades‑long safety record.

Under Kennedy’s leadership, The CDC has spent months revising its childhood immunization tables, moving several shots out of the universal category and into narrower risk‑based recommendations. One detailed review notes that, in all, the sweeping change reduces the universally recommended childhood vaccine schedule from 17 to 11, a shift that is now being implemented in a large, mobile health system where millions of children move between providers and insurance plans, according to Jan. That kind of churn makes it much easier for kids to fall through the cracks when vaccines are no longer treated as standard care at every well‑child visit.

The six diseases dropped from universal protection

The clearest way to see what Robert F. Kennedy Jr. believes kids do not need routine shots for is to look at the list of vaccines removed from the universal schedule. Under the new guidelines, vaccines for rotavirus, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, meningitis, RSV, and influenza are no longer on the universal recommendation list for all children, according to one detailed breakdown of the Vaccines for schedule. Another analysis of the policy shift similarly notes that among the core vaccines no longer recommended for all children are those that protect against rotavirus, RSV, and influenza, a change federal officials justified using HHS’s own modeling of disease burden and cost, as summarized in Among the new recommendations.

In practical terms, that means Kennedy is signaling that healthy children do not automatically need routine protection against severe diarrhea from rotavirus, liver damage from hepatitis A and B, bacterial meningitis, seasonal influenza, or respiratory syncytial virus. The CDC’s own fact sheet still stresses that Immunizations Recommended for All Children include vaccines that protect against highly contagious diseases and reduce the risk of transmission to others, but it now draws a sharper line between the 11 shots that remain universal and the six that have been downgraded, as reflected in updated Immunizations Recommended for. I read that as a policy compromise that keeps a core of vaccines in place while quietly inviting families to skip others unless they or their doctors push to stay fully covered.

What Kennedy says, and what federal health agencies still advise

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. now sits atop the nation’s foremost health agency as Secretary of Health and Human Services, yet his public statements about vaccines often clash with the scientific consensus. One detailed critique notes that, with no regard for the decades of data behind the prior schedule, he has used his position to promote an unscientific vaccine lineup that pares back protections without strong evidence that children were being harmed by the old approach, a tension highlighted in an analysis of Dangers of RFK. I see that conflict playing out inside the federal bureaucracy, where career experts are trying to preserve as much of the prior schedule as possible while responding to political pressure from the top.

At the same time, The CDC continues to emphasize that vaccines remain one of the safest and most effective tools to prevent serious childhood illness, even as it implements the new, slimmer schedule. Federal health pages still describe vaccines as a cornerstone of disease prevention and outline how immunization protects not only the child who receives the shot but also vulnerable people around them, a message that remains prominent on the main HHS site. I read that as a sign that, despite Kennedy’s skepticism, the underlying public health advice has not flipped to an anti‑vaccine stance, but rather has been narrowed in ways that may confuse parents about what is truly optional.

How the new schedule works in practice

On the new schedule, vaccines that remain universal are still given on a familiar timeline, starting with shots on the day of birth and continuing through early childhood, according to a detailed explanation of how the Centers for recommendations have been reorganized. The difference is that six vaccines have been carved out of that default track and moved into categories where they are suggested only for children with certain medical conditions, geographic exposures, or other risk factors. I worry that in a busy pediatric clinic, that nuance can easily translate into fewer conversations about those shots and more missed opportunities to vaccinate.

Federal vaccine recommendations for pediatric patients now explicitly distinguish between the 11 diseases that every child should be protected against and the six that are left to individual judgment, a structure laid out in the revised The CDC guidance. That might look tidy on paper, but in a health system where insurance coverage, clinic access, and record‑keeping vary widely, it creates a patchwork of protection. I see a real risk that children in wealthier, better organized practices will still receive most of the dropped vaccines, while kids in overstretched or rural clinics will go without, not because parents made an informed choice but because the shots were no longer framed as routine.

Doctors’ warnings and the Denmark comparison

Pediatricians and infectious disease specialists are already warning that the new policy is sowing confusion among parents. One report quotes doctors who say the changes are creating an environment that puts a sense of uncertainty about the value and necessity or importance of the vaccines that were removed, especially RSV, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and meningitis, and that some families are now skipping those shots without seeing a doctor to discuss the risks, concerns captured in a detailed Jan account. I share that concern, because once a vaccine is no longer presented as standard, it becomes much easier for misinformation or simple inertia to keep kids unprotected.

Supporters of the change sometimes point to countries like Denmark, which has a smaller set of routine childhood vaccines, as proof that the United States can safely trim its schedule. But the two countries differ in important ways: Denmark has 6 million people, universal health care, and a national registry that tracks every dose, while the United States is far larger, more fragmented, and lacks a single system where millions move between providers, as one analysis of Jan notes. I find that comparison misleading, because it glosses over the infrastructure that lets Denmark quickly spot and respond to outbreaks, a safety net the United States simply does not have.

Parents caught between politics and pediatrics

For families, the result of Kennedy’s overhaul is a tangle of mixed messages. On social media, one widely shared post spells out that RFK Jr. has officially changed the US pediatric vaccine schedule and warns that “Reduced recommendations do not mean reduced risk,” urging parents to talk with their own clinicians to make sense of the new categories, a sentiment captured in a detailed RFK breakdown. I think that is the crux of the problem: the federal government has stepped back from universal protection for six serious diseases, but it has not provided clear, accessible tools to help parents weigh the trade‑offs.

Health officials insist that vaccines remain available and that clinicians can still recommend every shot on the prior schedule for children who need them. The official line is that the new framework simply refines who is most likely to benefit, a message echoed in federal Jan analyses of disease burden. But from where I sit, the practical effect is that Kennedy has told parents that routine vaccines against rotavirus, hepatitis A and B, meningitis, RSV, and influenza are no longer essential for every child, even though the underlying infections have not become any less dangerous. In a country already struggling with vaccine hesitancy, that is a message with consequences that will only become clear as the next few respiratory seasons unfold.

More from Morning Overview