Elon Musk’s Starlink network was built to blanket the planet with low-cost internet, but a growing number of its satellites are now falling back to Earth every single day. As I look at the data and the scientists raising alarms, the story is no longer just about connectivity—it is about whether the world is sleepwalking into a new kind of environmental and safety risk in the sky.

The scale of the Starlink project means that even a small design trade-off can have global consequences once multiplied by thousands of spacecraft. With experts warning that deorbiting satellites are already altering the upper atmosphere and could threaten aircraft and people on the ground, Musk faces a new set of worries that can’t be solved with launch capacity alone.

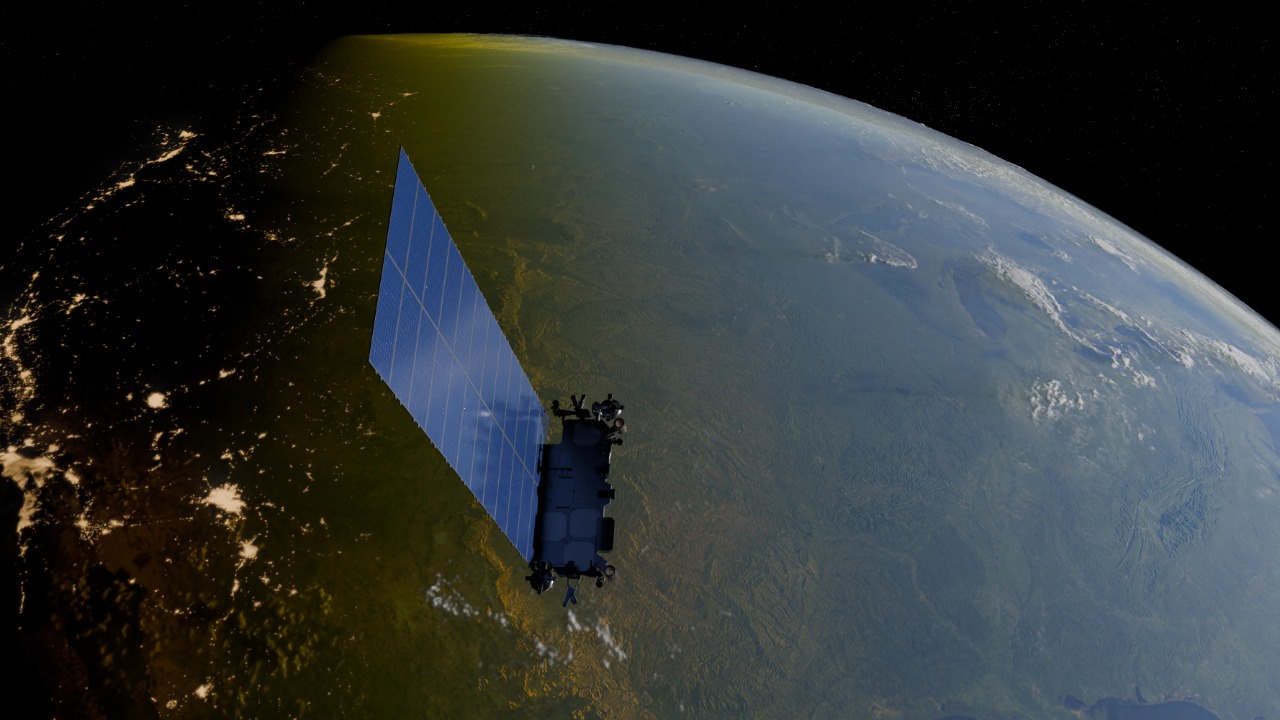

Starlink’s rapid growth meets a new kind of gravity

When I step back and look at Starlink’s trajectory, the sheer speed of its expansion is staggering: thousands of satellites launched in just a few years, with plans for tens of thousands more. That aggressive cadence has turned low Earth orbit into a dense shell of hardware, and now the return journey—those satellites falling back down—is starting to define the next phase of the story. Earlier this year, reporting showed that up to four Starlink units are in the process of reentering the atmosphere on any given day, a rate that transforms what might have been a rare event into a routine part of the global environment.

What makes this shift so striking to me is that the falling hardware is not a surprise glitch but a built-in feature of the system: the satellites are designed to operate for only a few years before burning up in the atmosphere. A detailed analysis of the constellation noted that the spacecraft are intentionally placed in low Earth orbit so they will naturally decay and disintegrate rather than linger as debris, yet that same design choice means the planet is now being showered with a steady stream of artificial material. One investigation into how Starlink satellites are falling to Earth daily underscored that this constant turnover is happening at the same time as more and more units are being sent to orbit, raising questions about how sustainable the model really is.

Daily reentries and the warning from space experts

As I dug into the numbers, the idea that “a satellite fell somewhere” stopped feeling like a rare headline and started to look like a daily background condition. Spaceflight specialists now estimate that up to four Starlink satellites are in some stage of orbital decay at any moment, each one gradually spiraling down until it hits the thicker layers of the atmosphere and breaks apart. That means dozens of reentries every month, and because the constellation is spread around the globe, the fallout is distributed over many regions rather than confined to a single corridor.

The concern I hear from experts is not just about the spectacle of streaks in the sky but about what those streaks are made of. One space analyst described how the satellites’ aluminum and other metals vaporize as they burn, injecting material into the upper atmosphere that was never there in such quantities before. In a focused warning that Starlink Satellites Keep Falling, a Space Expert Warns that this daily rain of debris is happening at the same time as more satellites are being launched, creating a feedback loop where the more Musk builds his network, the more material ends up burning in the sky.

Scientists flag environmental risks in the upper atmosphere

What troubles me most is how quickly the conversation has shifted from abstract orbital mechanics to concrete environmental impacts. Earlier this year, Scientists documented that 120 Starlink satellites fell from space in a single month, a figure that turns the upper atmosphere into a kind of industrial exhaust pipe. Each disintegrating spacecraft releases metallic vapour as it burns, and researchers are now trying to understand how that plume interacts with ozone chemistry, cloud formation, and the delicate balance of radiation that keeps the climate stable.

In their warnings, Scientists have emphasized that the satellites are designed to burn fully, leaving no large debris to hit the ground, but that doesn’t mean they vanish without a trace. Instead, the material is redistributed as fine particles and gases at high altitude, where it can linger and potentially alter atmospheric processes in ways we are only beginning to quantify. A detailed report on how failing Starlink satellites worry scientists highlighted that 120 fell in Jan and that the environmental risks from this metallic vapour are not yet fully understood, underscoring how Musk’s orbital strategy is now entangled with planetary-scale questions.

Avi Loeb’s “new threat from the sky” and the numbers behind it

Among the voices pushing this issue into the mainstream, astrophysicist Avi Loeb has been unusually blunt, describing Musk’s falling satellites as a “new threat from the sky.” When I read his comments, what stands out is not alarmism but a sober recognition that the system is working exactly as designed: the satellites have an average lifespan of about five years, after which they are expected to reenter and burn up. Loeb has argued that this predictable churn means we can no longer treat each reentry as an isolated event; instead, we need to think of it as a continuous industrial process happening overhead.

Loeb’s concerns have been amplified by coverage that tracks how quickly the reentry rate is rising. One report by Zach Kaplan noted on Oct 10, 2025, and then Updated on Oct 11, 2025, that the number of satellites falling back to Earth could rise by 61% each year if current launch plans continue, a projection that turns today’s daily reentries into tomorrow’s constant shower. That same analysis pointed out that 37 satellites had already come down in a recent period, illustrating how fast the tally can climb. In that context, Loeb’s description of Elon Musk’s falling satellites as a “new threat from the sky” is less a rhetorical flourish than a summary of the math, and it is why I link his warning directly to the data on Elon Musk’s Starlink satellites falling to Earth.

Design choices: five-year lifespans and complete burn-up

From a purely engineering standpoint, I can see why SpaceX opted for short-lived satellites that burn up completely. By giving each Starlink unit a lifespan of about five years and placing it in low Earth orbit, the company reduces the long-term risk of dead hardware clogging space and triggering catastrophic collisions. The idea is that when a satellite fails or reaches the end of its mission, atmospheric drag will eventually pull it down, where it disintegrates before any large fragments can reach the surface.

The trade-off, however, is that this design pushes the environmental burden from orbital debris to atmospheric pollution. A detailed account of how Starlink satellites have a lifespan of about five years explains that they are specifically designed to burn up completely in the Earth’s atmosphere, with some researchers warning that the resulting particles could contribute to warming the atmosphere. In other words, Musk has solved one problem—space junk—by creating another, and the question now is whether regulators and scientists can keep up with the pace of his design decisions.

“Already falling” and why the trend will only accelerate

When I compare early Starlink launches to the current phase, the most striking change is how normal falling satellites have become. SpaceX’s orbital internet fleet is no longer a static constellation; it is a conveyor belt, with new units going up as older ones come down. Analysts tracking the orbits have concluded that the satellites are already falling out of low Earth orbit at an increasingly alarming rate, and that the trend is baked into the architecture of the system rather than being a temporary glitch.

Some observers have gone further, arguing that the pattern of failures and reentries points to a design problem as much as a planned lifecycle. They note that as the constellation grows, even small reliability issues can translate into dozens of extra reentries each year, compounding the environmental and safety concerns. A close look at how Starlink satellites are already falling suggests that the rate will only get worse as more spacecraft are added, raising the possibility that Musk will have to revisit core design choices if he wants to keep the system politically and environmentally viable.

Balancing global internet access with risks from above

For all the worry, I don’t want to lose sight of why Starlink exists in the first place. In remote villages, disaster zones, and war-torn regions, the network has become a lifeline, delivering broadband where fiber and cell towers either never existed or have been destroyed. That humanitarian and economic upside is real, and it explains why governments and consumers have been willing to tolerate a certain level of orbital clutter and reentry risk in exchange for connectivity that would otherwise be out of reach.

The challenge for Elon Musk now is that the trade-offs are becoming harder to ignore as the numbers climb. With up to four satellites falling toward Earth on any given day, 120 recorded in a single month, and projections that the reentry rate could rise by 61% each year, the burden of proof is shifting: it is no longer enough to say the satellites burn up harmlessly. As I weigh the evidence from Oct 8, 2025, Oct 9, 2025, Oct 10, 2025, and Feb 6, 2025, and read experts like Loeb warning that Starlink’s falling hardware represents a new threat from the sky, it is clear that Musk’s next big challenge is not just launching more satellites—it is convincing the world that the daily rain of metal and vapour above our heads will not come back to haunt us on the ground.

More from MorningOverview