Space telescopes have always been defined as much by their rockets as by their mirrors. When every kilogram to orbit costs a fortune, engineers are forced into intricate origami, exotic materials, and decade-long development cycles. With SpaceX’s Starship class rockets promising far larger payloads at dramatically lower launch prices, the economics and design logic of future observatories could shift just as radically as the science they enable.

If that shift materializes, the next generation of space telescopes may look less like fragile jewelry and more like robust industrial hardware, built quickly and upgraded often. Instead of one-off flagships such as The James Webb Space Telescope, agencies and universities could field fleets of specialized instruments, each optimized for a particular slice of the cosmos rather than constrained by the tightest mass and volume limits.

Heavy-lift rockets rewrite the basic telescope trade-offs

The central promise of Starship class vehicles is simple: far more volume and mass to orbit at a fraction of today’s cost. Analyses comparing the Space Launch System and Starship highlight how the latter’s Payload Volume and overall capacity are designed to dwarf the Space Launch Syst benchmarks, with the aim for Starship to fly at a much lower price per launch than the cost of an SLS launch, fundamentally changing the budget math for large missions once it is operational and reliable, as detailed in one comparison. Superheavy-lift rockets like SpaceX’s Starship and NASA’s Space Launch System are described by researchers as a new class of infrastructure that can carry observatories which would have been impossible to launch on earlier vehicles.

That extra headroom does more than just scale up mirror diameters. It relaxes the brutal engineering trade-offs that have dominated space astronomy since the first orbital telescopes. Instead of shaving every gram from support structures and folding optics into cramped fairings, designers can prioritize stiffness, thermal stability, and ease of integration. Work on new concepts such as a deep infrared observatory called Origins and other large missions shows how teams are already sketching instruments around the capabilities of these superheavy rockets, with one analysis arguing that such launchers could transform astronomy by making space telescopes cheaper through simpler, more robust designs that fully exploit their lift capacity, as explored in a recent study.

From jewel-like flagships to cheaper, better workhorses

For decades, missions like The James Webb Space Telescope have been treated as once-in-a-generation bets, with budgets and schedules that balloon under the pressure of perfection. Researchers examining how to make space telescopes cheaper and better argue that this model is unsustainable, and that the path forward lies in standardizing components, simplifying deployment, and investing more in the software running these sophisticated telescopes rather than in ever more elaborate mechanical gymnastics, a case laid out in detail by a group of Researchers. If launch constraints ease, it becomes far more realistic to build multiple mid-cost observatories instead of a single ultra-delicate flagship, each one iterating on proven bus designs and instrument suites.

Starship’s scale fits neatly into that vision. With a larger fairing and higher mass allowance, a telescope can be built more like a ground-based instrument, with straightforward mechanical construction under Earth’s gravity and fewer moving parts. Advocates for a dedicated exoplanet observatory argue that Starship can allow greatly reduced space development costs, provided that telescope and instrument designers internalize the new constraints and stop designing as if every kilogram is priceless, a point made explicitly in one detailed argument for a next-generation exoplanet mission that treats Starship as the baseline launcher. In that framing, the real revolution is not just the rocket, but the willingness of mission planners to accept that cheaper, more frequent launches can support a portfolio of telescopes instead of a single irreplaceable crown jewel.

How SpaceX’s cost-cutting playbook spills into astronomy

Starship’s potential impact on telescope budgets is rooted in the broader way SpaceX has already reshaped launch economics. At its Hawthorne facility, SpaceX has vertically integrated design and manufacturing, using in-house production, rapid iteration, and reusable hardware to drive down the price of getting to orbit, a strategy that one Stock Review notes offers three main benefits for cost and schedule. If even a fraction of those savings translate to superheavy flights, the launch line on a telescope’s budget spreadsheet could shrink from a dominant cost driver to a manageable line item.

That shift would ripple through mission design. Also, Starship’s heavier weight limit would mean engineers need not shave every ounce they could off the telescope, since cheaper, more powerful rockets could be used at much lower cost, as one analysis of Starship’s implications for astronomy points out. Instead of exotic deployable mirrors and ultra-thin structures, teams could choose thicker supports, more generous margins, and simpler thermal systems, all of which cut engineering risk and shorten development timelines, which in turn reduces the overhead that has historically plagued flagship missions.

New mission architectures in the era of Starship, New Glenn, and SLS

The emerging heavy-lift ecosystem is not limited to SpaceX. Starship, New Glenn, and SLS are all being positioned as enablers for a new generation of observatories, including the Habitable Worlds Observatory that NASA has identified as a priority for studying Earth-like exoplanets. Earlier missions relied on smaller vehicles such as Ariane 5, which launched the James Webb Telescope to Lagrange point L2, but future designs are already being scoped around the larger fairings and higher capacities of these new rockets, as outlined in a detailed look at how Starship, New Glenn, SLS, and even a proposed Starship V could reshape telescope planning. That analysis underscores how launch vehicle choice is now a first-order design decision, not an afterthought.

Superheavy-lift rockets like SpaceX’s Starship could change everything about how astronomers think about observing the universe from space. With larger, cheaper telescopes, scientists could take the broad view of the cosmos, capturing faint signals and wavelengths otherwise blocked by Earth’s atmosphere, a prospect highlighted in a recent overview of how Superheavy launchers might transform astronomy. In that scenario, the most ambitious missions, from ultraviolet surveyors to far-infrared mappers, become less constrained by launch packaging and more by the scientific questions they are built to answer.

Designing telescopes specifically for Starship class rockets

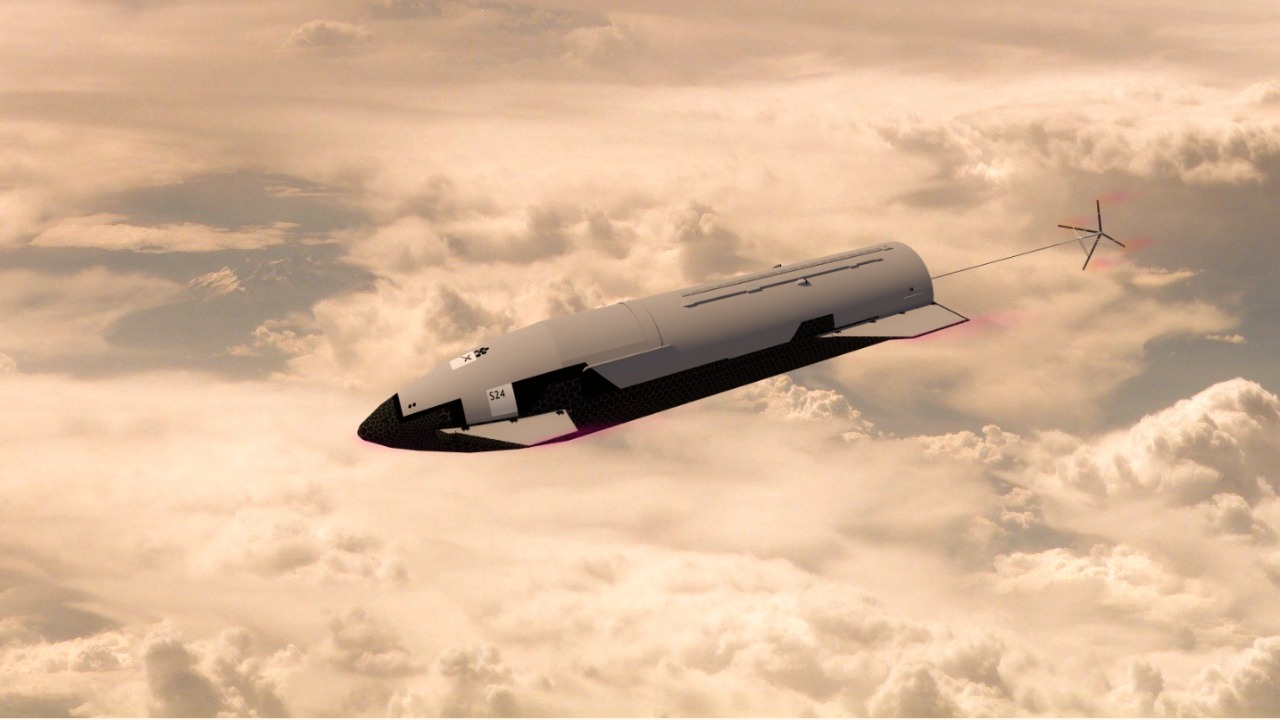

If Starship flights become routine, the most interesting telescopes may be the ones that could not exist on any other rocket. Enthusiasts and engineers have already begun sketching concepts that treat Starship as not just huge, but also very very cheap and with the capability of taking something big from space and bringing it back, which opens the door to on-orbit servicing, refurbishment, and even return of entire observatories for upgrades, as discussed in a community analysis of what Starship could mean for telescope design. In that vision, mirrors and instruments are built with maintenance in mind, using modular components that can be swapped out over time instead of being locked into a single, unserviceable configuration.

Designing with these possibilities in mind would push agencies and contractors to rethink their entire development pipeline. Rather than treating each observatory as a bespoke sculpture, they could adopt a more industrial approach, building multiple copies of a standard bus, iterating instruments across launches, and planning for midlife upgrades delivered by the same class of rocket that launched the original mission. If that happens, Starship class vehicles will not just cut the cost of putting telescopes into space, they will change what a space telescope is: from a fragile, one-shot masterpiece into a durable, evolving tool that can keep pace with the questions astronomers want to ask.

More from Morning Overview