Biologists are confronting a problem they thought they had mostly solved: what, exactly, counts as life. A wave of discoveries at the edges of biology has produced organisms and quasi-organisms that slip through the usual categories of animal, plant, fungus, bacterium, virus, or archaea. The result is a growing list of lifeforms that scientists can describe in exquisite detail but still struggle to classify.

From a microscopic parasite that behaves like a stripped‑down shadow of life, to strange RNA structures inside our own bodies, to fossil traces of something that tunneled through solid rock, each new find forces researchers to redraw the boundaries of the living world. I see a pattern emerging in these reports: the more closely scientists look, the more nature refuses to fit inside the neat boxes of the textbooks.

The parasite that lives like a virus but is not one

One of the most striking examples is a microscopic parasite named Sukunaarchaeum mirabile, which researchers describe as “truly weird” and perhaps the closest thing yet to a living boundary case. It is so reduced that it cannot survive on its own, instead attaching to a host cell and siphoning off what it needs, yet it still carries hallmarks of cellular life rather than behaving like a classic virus. Jan and other scientists who examined Sukunaarchaeum mirabile argue that its existence pushes at the edge of what counts as “alive,” because it blurs the line between a dependent cell and a molecular parasite.

Unlike a virus, which is essentially genetic material wrapped in protein, this parasite retains enough of its own machinery to look like a cell that has been pared down to the bare minimum. At the same time, it is so dependent on its host that it cannot grow or reproduce without that intimate connection, which is why Jan and the scientists who studied it describe it as a microscopic parasite that might be the closest thing we have found to a living limit case. In their account, scientists have discovered a truly weird microscopic parasite that forces them to revisit the criteria they use to define life at all.

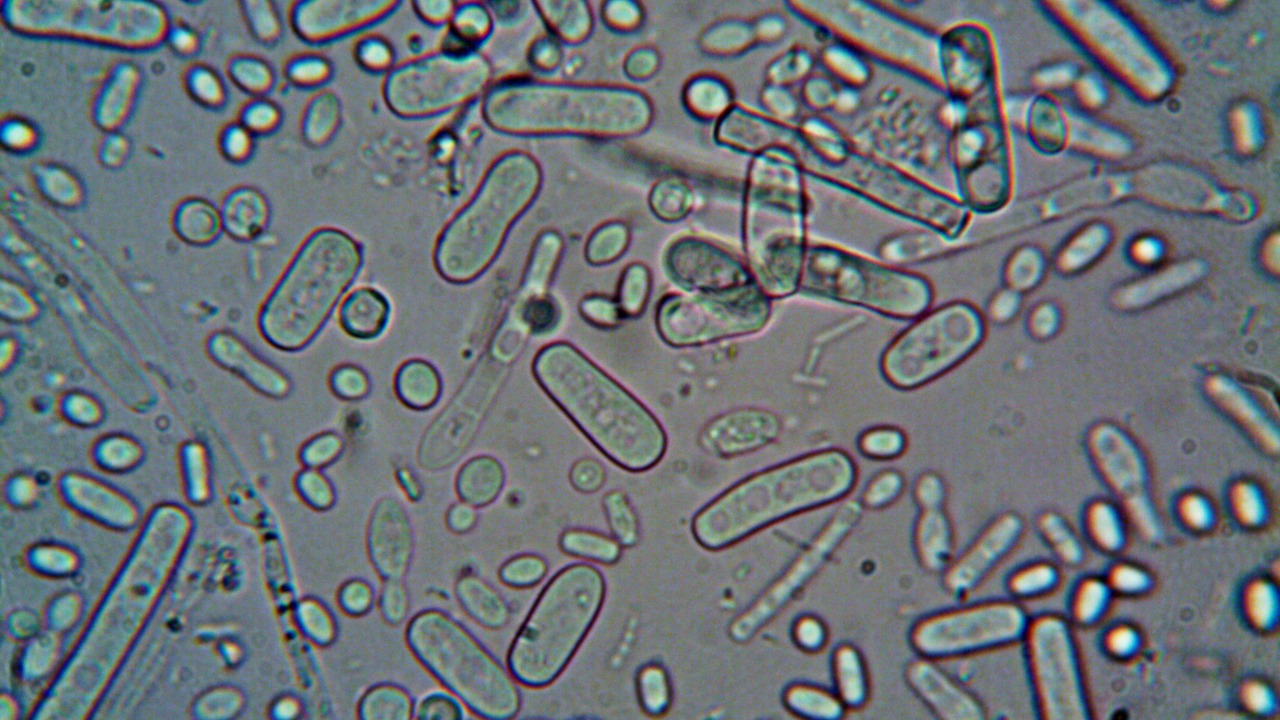

A sun-shaped microbe that could redraw the tree of life

Another discovery that unsettles the standard categories is a microorganism with a striking, sun-like appearance that researchers have named Solarion arienae. Under the microscope, this organism forms a radiant disk with filament-like rays, a structure that is as visually arresting as it is biologically puzzling. Genetic analysis suggests that Solarion arienae may not fit comfortably within any known microbial group, raising the possibility that it represents a lineage that split off very early from other forms of life.

What makes Solarion arienae especially intriguing is what lies inside that sun-shaped body. Researchers report that its internal organization and genetic makeup hint at a complex evolutionary history, potentially involving interactions with an ancient bacterium that may have contributed to its current form. The team behind the work has argued that the discovery of Solarion arienae could represent an entirely new branch on the tree of life, one that forces evolutionary biologists to rethink how early microbes diversified.

The ancient giant that is not quite plant, not quite fungus

The classification problem is not limited to microbes that live today. Paleontologists have been wrestling with a mysterious ancient creature that refuses to sit neatly on the tree of life, even with modern tools. Fossils of this organism show a towering, column-like structure that for decades defied explanation, with some researchers arguing it might be a primitive plant, others suggesting an animal, and still others proposing a fungus. The latest work, highlighted in a report that grouped it among Top Stories alongside a Super wolf moon, leans toward the idea that it was likely a giant ancient fungus, but even that conclusion is hedged with caution.

The difficulty is that the fossil record preserves shape and texture far more readily than it preserves the molecular signatures that would settle the debate. The scientists who revisited the specimen used comparisons with modern fungi and plants to argue that its growth patterns and internal structure most closely resemble a fungus, yet they acknowledge that it does not match any living group exactly. In their account, the scientists baffled at a mysterious ancient creature are confronting the limits of classification when evolution has had hundreds of millions of years to erase the intermediate forms.

Mysterious tunnels in desert rock and the life that carved them

Geologists are also stumbling onto traces of life that do not resemble anything in the standard catalogs. In one desert region, erosion exposed a network of bizarre tunnels inside rocks, intricate burrows that twist and branch in ways that do not match any known geological process. At first glance they might be mistaken for the work of insects or worms, but their scale, shape, and location inside solid stone point to a different origin. Dec and other geologists who examined the site concluded that the tunnels were likely formed by a microorganism unlike anything previously documented.

The same landscape has yielded fossil burrows in the desert’s sedimentary layers that appear to have been created by an unknown lifeform, adding to the sense that something very unusual was once active there. In a detailed account of this Surprising Discovery in the Desert The report describes how erosion revealed structures that could not be explained by wind, water, or simple chemical weathering, and instead pointed toward biological activity by a microbial community that left behind no obvious body fossils. The researchers describe a microbial mystery that carved its way through rock, a reminder that life can leave its mark in architecture even when its own cells are long gone.

Unknown microbes living inside ancient rocks

Some of the most unsettling finds are not fossils at all but living organisms sealed inside rocks that predate complex life on the surface. When researchers split open a rock that formed roughly two billion years ago, they found living microbes tucked away in microscopic pores, apparently surviving in isolation from the surface world. The discovery suggests that microbial life can persist for astonishing spans of time in deep, stable environments, feeding on chemical gradients rather than sunlight. It also hints that the early Earth may have been teeming with similar communities hidden in the crust.

Those living microbes inside a two‑billion‑year‑old rock have significant implications for how life began on Earth and how it might endure on other worlds. If organisms can survive in such extreme, nutrient‑poor conditions for geological timescales, then subsurface habitats on Mars or the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn may be more promising than previously thought. The team behind the work argues that the find should reshape how we search for life on other planets, because the discovery has significant implications for astrobiology as well as for our understanding of Earth’s own deep biosphere.

Rock-burrowing microbes that defy geological expectations

Other rocks tell a different but equally puzzling story. In marble and limestone formations, scientists have identified networks of microscopic tunnels and chambers that do not resemble any known pattern of mineral growth or erosion. The structures are too organized and purposeful to be random fractures, yet they do not match the traces left by familiar burrowing organisms. Researchers studying these formations concluded that they are likely the work of an unidentified microorganism that adapted to life inside solid stone, slowly dissolving and reshaping the rock around it.

These rock‑burrowing microbes, if confirmed, would expand the known range of environments that life can colonize and would force geologists to reconsider some features they had previously written off as purely chemical. The tunnels suggest a metabolism that can extract energy and nutrients from minerals, a strategy that could be relevant to life on other rocky worlds with little surface water or sunlight. The team behind the work notes that these structures do not resemble any known geological process, and that they may be the work of an unidentified microorganism that offers a new example of how life adapts to extreme environments, as described in a report on mystery microbes burrowed into rock millions of years ago.

Obelisks: strange RNA structures inside the human body

The most intimate classification puzzles may be unfolding inside our own bodies. According to a new study from bioRxiv that has yet to be peer reviewed, researchers have identified a new type of life form in the human body that does not match any known category of virus, bacterium, or cellular organism. These entities, dubbed “obelisks” or “oblins” in some reports, appear to be built around RNA and proteins, but their genetic code and structure differ enough from familiar viruses to suggest they might represent a different type of organism. According to the scientists behind the work, the genetic differences are so pronounced that they argue these entities may be a different type of organism altogether, as summarized in a report that notes According to a new study from bioRxiv they may not fit existing labels.

These obelisks were first flagged in large‑scale genetic surveys of the human microbiome, where they appeared as recurring RNA sequences that did not match any known virus or cellular gene. They seem to assemble into stable structures inside the gut and other tissues, interacting with the surrounding microbial community in ways that are still poorly understood. The researchers caution that the work is preliminary and that more evidence is needed before declaring obelisks a new domain of life, but the early data already challenge the assumption that everything inside the human body can be sorted into familiar categories of germs and cells.

New forms of life inside humans that do not match any known class

Follow‑up work has only deepened the mystery. Dec reports describe scientists who discover new forms of life inside human bodies that do not match anything biology has classified, focusing on RNA structures that behave like independent entities rather than simple genetic fragments. These structures appear to replicate, evolve, and interact with their environment, yet they lack the full cellular machinery that would make them straightforward microbes. The phrase “Scientists Discover New Forms of Life Inside Human Bodies That Don Match Anything Biology Has Classified” captures the sense of unease among researchers who are used to fitting new finds into existing boxes.

One detailed account notes that these RNA structures are found in association with the human microbiome and may influence it in ways that remain poorly understood, potentially affecting how microbes in the gut and other tissues behave. The scientists involved emphasize that they are not dealing with a conventional virus or bacterium, but with something that sits in between, a self‑organizing system that uses RNA to carry information and perhaps to direct its own replication. In that context, the report on Scientists Discover New Forms of Life Inside Human Bodies That Don Match Anything Biology Has Classified reads less like a curiosity and more like a sign that our own bodies harbor ecosystems we have barely begun to map.

Obelisks as a potential new class of life

As more groups look for obelisks, they are finding them in surprising places. Dec coverage by Jordan Joseph describes how scientists find new forms of life inside humans that function as RNA carriers, with obelisks showing up in samples from the mouth, gut, and other microbiomes. These structures appear to be associated with bacteria in the human body, including strains linked to the University of North Carolina research teams that first cataloged them. Joseph notes that every time we think we are close to fully understanding the human body, something fresh and unexpected appears, and obelisks are a prime example of that pattern.What sets obelisks apart is not just their presence but their behavior. They self‑organize into rod‑like shapes, a physical structure that inspired their name, and they appear to replicate independently of the host cell’s genome. Detailed analysis suggests that they may represent an entirely new class of life, one that uses RNA as its primary genetic material but does not conform to the known families of RNA viruses or viroids. In that sense, the report that ByJordan Joseph, Every time we think we’re close to fully understanding the human body we are reminded that the microbiome still hides surprises, and obelisks may be the most radical of them.

From gut oddities to a proposed new domain

Specialists in microbiology and genomics are beginning to treat obelisks not as isolated curiosities but as candidates for a new domain‑level category. One technical report notes that they self‑organize into rod‑like shapes, which is how they got their name, and that their genetic sequences do not cluster with any known viral or cellular lineages. The authors argue that obelisks may represent an entirely new class of life, a claim that, if confirmed, would rival the discovery of archaea in terms of its impact on biology. They emphasize that these entities are not simply defective viruses or stray RNA fragments, but coherent systems with their own evolutionary history.

The same work highlights how obelisks interact with the human microbiome, suggesting that they may influence which bacteria thrive in the gut and how they respond to environmental changes. If so, they could have implications for health and disease that go far beyond their classification puzzle. The technical description notes that They (obelisks) self‑organize into a rod‑like shape and may represent an entirely new class of life, a claim summarized in a detailed analysis of how They ( obelisks ) self-organize into a rod-like shape and challenge existing taxonomies.

Why classification is breaking down at the edges of life

Stepping back from the individual discoveries, a pattern emerges. Many of these entities sit at the margins of what biologists have traditionally called life: parasites like Sukunaarchaeum mirabile that cannot live without a host, rock‑burrowing microbes that leave only their tunnels behind, RNA structures like obelisks that behave like organisms but lack cells. Each case forces scientists to revisit the criteria they use to define life, from metabolism and reproduction to genetic continuity and evolutionary history. The more they look at the extremes, the more they find systems that satisfy some criteria but not others.

That tension is evident in the way researchers talk about obelisks in the gut. One analysis notes that, however rarely an entirely new class of organism is discovered, the evidence for obelisks is strong enough that some scientists are already treating them as a distinct category. They have given them a name, Obelisks, related to their apparent physical structure, and are mapping where they appear in the human body and beyond. The report emphasizes that, However rarely has an entirely new class of organism been discovered, the case for Obelisks, related to their apparent physical structure as a new form of life is strong enough to merit serious consideration, even if the final verdict will take years.

The desert tunnels and a parasite that rewrites dependence

Returning to the desert, the story of the mysterious tunnels in rock shows how classification can be challenged even when the organism itself is gone. Geologists like Dec who study these formations emphasize that the tunnels do not match any known abiotic process, which leaves a biological agent as the most plausible explanation. Yet without preserved cells or DNA, they can only infer the nature of that agent from the architecture it left behind. The result is a category of “unknown lifeform” that is defined more by its impact on the environment than by its own anatomy.

In parallel, the case of Sukunaarchaeum mirabile shows how dependence on a host can blur the line between organism and component. Jan and the scientists who studied this parasite highlight that it relies entirely on its host for survival, to the point that it cannot perform basic functions on its own. At the same time, it retains enough of its own identity to be more than a mere extension of the host cell. In their description, scientists describe a microscopic parasite that depends on its host for survival, a reminder that life can be both autonomous and dependent in ways that strain the usual definitions.

Why these baffling lifeforms matter beyond curiosity

It might be tempting to treat these discoveries as isolated oddities, but together they point to a deeper shift in how biologists think about life. The traditional tree of life, with its neatly separated branches for animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, archaea, and viruses, is giving way to a more tangled picture that includes parasites like Sukunaarchaeum mirabile, sun‑shaped microbes like Solarion arienae, ancient giants that were likely giant fungi, rock‑burrowing microorganisms, and RNA‑based entities like obelisks. Each new find adds another twist to that picture, suggesting that the diversity of life, both past and present, is far greater than the categories we have used to describe it.

For me, the most striking lesson is that classification is not just a bookkeeping exercise, it shapes how we search for life in the first place. If we assume that all life must look like familiar cells or viruses, we risk overlooking entities that operate on different principles, whether they are hiding in our own microbiomes or in the rocks of distant planets. The reports on Geologists discover bizarre tunnels in desert rocks and on previously unknown RNA structures inside humans are reminders that life can be stranger, more adaptable, and more inventive than our current theories allow. The lifeform scientists cannot yet classify is not a single organism, it is a growing collection of puzzles that together are forcing a quiet revolution in biology.

More from MorningOverview