Robots that can think and move are no longer confined to factory floors or humanoid prototypes. Researchers have now shrunk fully programmable machines to a size smaller than a grain of sand, packing sensing, computation, and locomotion into specks you could balance on an eyelash. The achievement pushes robotics into a realm where individual devices are almost invisible, yet collectively promise to reshape medicine, engineering, and how I think about computers themselves.

The leap comes from a collaboration that solved a four-decade puzzle in micro-robotics: how to give tiny machines both brains and bodies without bulky batteries or external tethers. Instead of scaling down familiar designs, the teams behind these devices reimagined what a robot is, fusing solar-powered circuits, flexible legs, and minimalist instruction sets into a new class of autonomous machines.

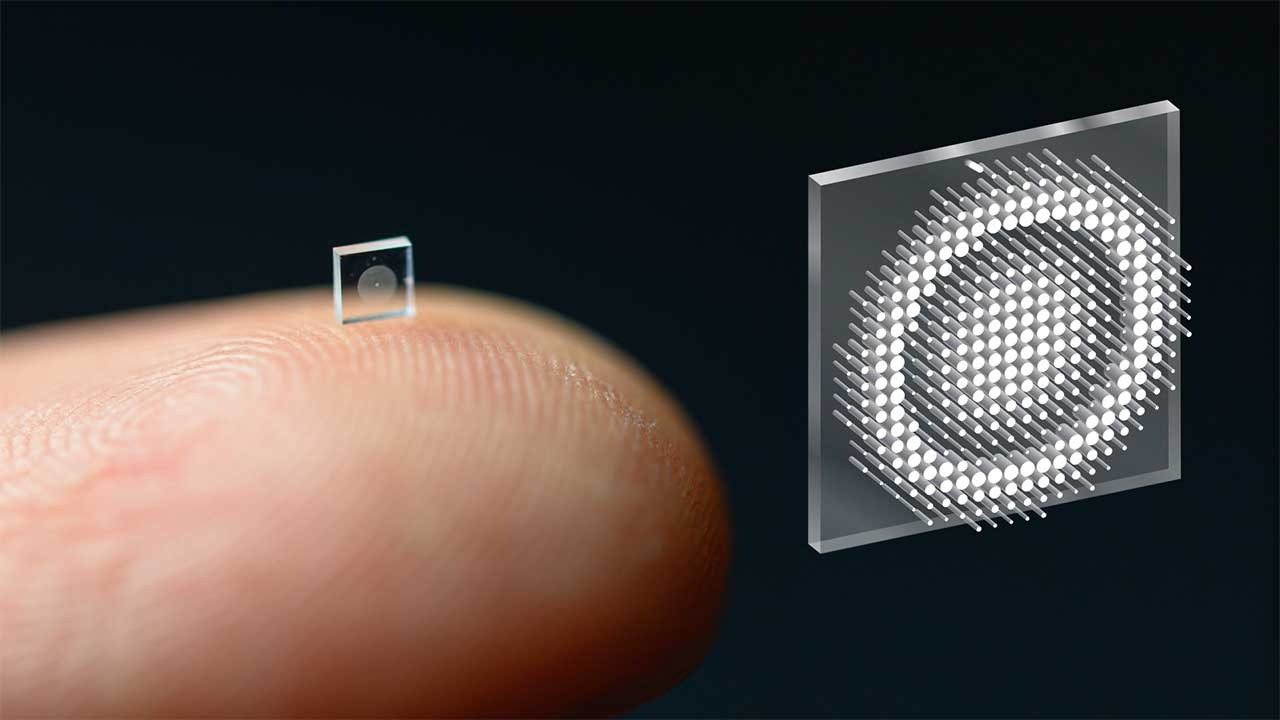

The breakthrough: a computer on legs the size of a salt grain

The core advance is deceptively simple to describe: a complete computer system, including memory and logic, integrated directly onto a microscopic walking robot. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania built what they describe as the smallest fully programmable robots yet, each one smaller than a grain of salt yet still able to sense its surroundings, process information, and respond with coordinated motion. Instead of relying on external computers, the control logic is etched into the same silicon that forms the robot’s body, turning each device into a self-contained system.

Earlier work had already shown that it was possible to make microscopic machines crawl and even “dance,” but those devices were essentially remote-controlled. As Miskin and colleagues detailed in Science Robotics and Sciences, their salt-grain-sized walkers could only move forwards and backwards when driven by external signals. The new generation goes further by embedding decision-making directly on board, so the robot can interpret sensor data and adjust its gait without a human or a separate computer issuing every command.

How a speck of silicon learns to “sense, think and act”

At the heart of these machines is a stripped-down but fully functional computing architecture that translates environmental inputs into motion. Researchers just cracked a four-decade engineering puzzle that had been taunting scientists since the 1980s, integrating a solar-powered microcontroller with actuators and sensors on a chip-scale robot so it can, as one account put it, think for itself. The control system is not “intelligent” in the human sense, but it can run simple programs that interpret sensor readings and trigger specific movement patterns, which is enough to qualify as autonomous behavior at this scale.

One of the clever tricks is how information is encoded in the robot’s motion. Scientists designed a special computer instruction that encodes a value, such as a measured temperature, in the wiggles of a flexible leg, effectively turning the robot’s gait into a data signal. That instruction set, described in coverage of scientists create robots smaller than a grain of sand, lets the robot both move and communicate what it has sensed without needing a separate radio or data link. In effect, the pattern of its steps becomes a compressed report about the environment, readable under a microscope or by optical instruments tuned to track those tiny motions.

From dancing specks to medical scouts inside the body

Once you can build a robot that is smaller than a grain of salt and still capable of sensing, thinking, and acting, the most obvious application is medicine. A robot the size of a grain of salt offers a vision of future procedures in which doctors could monitor the health of a patient’s cells without surgery, sending swarms of devices to inspect tissues from the inside. Reporting on robot the size describes how such machines might one day navigate through the body, powered by light or chemical gradients, to deliver targeted therapies or gather diagnostic data that is impossible to capture from outside.

Some of the most vivid scenarios come from work that imagines these robots as tiny clinicians. Scientists Just Built a Robot Smaller Than a grain of salt that could, in principle, navigate a bloodstream to destroy tumors, repair nerves, or monitor cell health in real time. Another report describes how a robot smaller than a grain of salt can sense, think and inside the body, with the feat again credited to a partnership of researchers at University of Pennsylvania and University of Michigan. The idea is not science fiction anymore, even if clinical use is still years away: the hardware now exists, and the challenge shifts to biocompatibility, control, and regulation.

Engineering at the edge: legs, light, and liquid environments

Building a robot at this scale is not just a matter of shrinking electronics, it is also a mechanical and materials challenge. In robotics, as in so many things, small is beautiful, but making machines really small is hard because forces like surface tension and viscosity dominate. One analysis of robots smaller than of sand explains how each leg is driven by a tiny actuator that bends when hit with light, pushing on nearby water molecules to generate motion. At this scale, the robot is not so much walking as it is swimming through a syrupy world where every step is a negotiation with fluid physics.

Unlike traditional underwater drones, this new class of devices does not carry propellers or batteries. Instead, scientists have built robots smaller than a grain of salt that can sense their environment, make decisions, and move completely untethered, with energy harvested from external light sources. Coverage of these scientists notes that the robots operate in liquid environments where conventional designs would fail, hinting at future roles in groundwater monitoring or industrial systems as well as inside the human body. The engineering trade-offs are stark: every extra feature, from communication to more complex sensors, adds area and complexity, so the teams have focused on minimal, robust designs that can be mass-produced on silicon wafers.

What comes next: swarms, self-healing, and a new kind of infrastructure

The current prototypes are impressive, but they are also just the first wave of a broader shift toward micro-scale machines. Scientists at the University of Pennsylvania have framed their work as a platform for miniaturised robotics and smart technology, suggesting that future versions could carry more sophisticated sensors or even basic forms of on-board learning. A short video from Penn Engineering introduces these devices as the world’s smallest fully programmable robots, already helping construct micro-scale devices in the lab. That hints at a future in which such robots are not just tools for medicine, but also workers inside semiconductor fabs or chemical plants, assembling structures too small for any conventional machine.

Other researchers are already exploring how tiny robots that can think, move, and even heal themselves, smaller than a grain of sand, could change medical and engineering fields. One report describes how Each robot in such a system might repair minor damage to its own structure, extending its useful life inside harsh environments like the bloodstream or industrial reactors. Long before that vision is fully realized, the broader research community has been clear about the stakes: controlling systems on micro-scales could lead to a revolution in many critically important fields of science and engineering. As one proposal on Broader Research Impacts put it, mastering such control could make it possible to non-invasively repair tissue and save lives, turning today’s salt-grain robots into tomorrow’s invisible infrastructure.

For now, the most grounded assessment comes from the teams closest to the work. Jan reports describe how By Daniel Akst and others have chronicled the way these robots blur the line between computer chips and living systems, while Dec coverage of Researchers emphasizes how far the field has come since the first simple walkers. I see a pattern in all of this: as the robots shrink, the ambitions grow, from single devices that can crawl under a microscope to vast swarms that might one day patrol our bodies, our infrastructure, and even our environment, quietly doing work that used to require scalpels, scaffolding, or entire factories.

More from Morning Overview