Conjoined twins, a rare phenomenon affecting approximately 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 100,000 births worldwide, present unique medical challenges. When one twin dies, their shared physiology can lead to immediate life-threatening complications for the surviving twin. A notable case involved Nepalese conjoined twins who underwent separation surgery in 2001, but recent reporting underscores the ongoing risks in such scenarios, where the death of one twin often results in the swift demise of the other without intervention.

Understanding Conjoined Twins

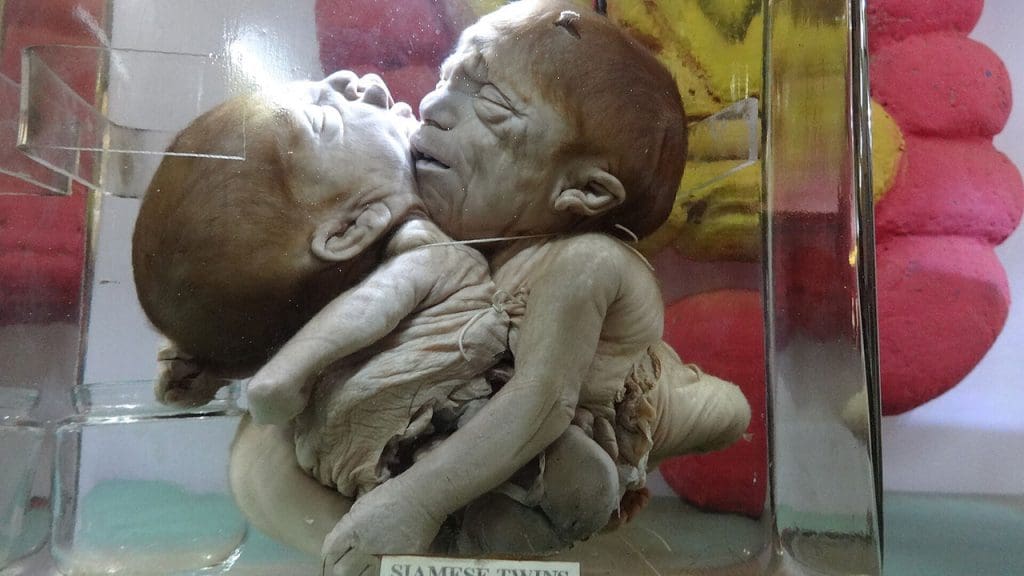

Conjoined twins are monozygotic twins who fail to fully separate during embryonic development, resulting in shared body parts like organs or limbs. The types of conjoinment include thoracopagus (chest-joined) and craniopagus (head-joined), with incidence rates of about 1 in 200,000 live births globally. This phenomenon adds complexity to their physiology and potential survival outcomes if separated or if one dies.

Diagnostic methods like ultrasound and MRI are used prenatally to identify conjoinment and plan for outcomes. These imaging techniques can reveal shared vascular systems that make independent survival difficult. Despite the challenges, medical advancements have made it possible to identify and manage conjoined twins more effectively than ever before.

The Biological Impact of One Twin’s Death

When one conjoined twin dies, the immediate physiological effects can be devastating for the surviving twin. Due to their interconnected systems, complications such as blood loss, infection transmission through shared circulation, or organ shutdown can occur, often leading to death within hours or days without emergency separation.

Shared vital organs, like a conjoined heart or liver, exacerbate risks. The surviving twin’s body may enter shock from the sudden imbalance of blood flow and toxins. Metabolic and immunological responses, including the release of inflammatory cytokines, can overwhelm the survivor’s system. These challenges highlight the urgent need for medical intervention when one conjoined twin dies.

Historical and Real-World Cases

The case of Chang and Eng Bunker, the original “Siamese twins” born in 1811 in Siam (modern-day Thailand), provides an early understanding of the phenomenon. They lived until 1874 but died within hours of each other due to shared circulatory strain. This case illustrates the inherent risks and challenges associated with conjoined twins.

In more recent times, the 2001 separation of Nepalese conjoined twins Ganga and Jamuna Mondal at age 16 in Singapore was a significant milestone. Successful surgery allowed them to lead independent lives, but the high mortality risk if one had died pre-separation underscores the precarious nature of such cases.

Modern Medical Interventions and Outcomes

Emergency separation surgeries post-death of one twin involve multidisciplinary teams using advanced imaging and 3D modeling. However, these procedures carry up to 50% mortality rates for the survivor due to incomplete organ sharing. Despite the risks, these surgeries represent the best chance for the surviving twin to live an independent life.

Supportive care options like ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) can stabilize the surviving twin temporarily. Success rates for such interventions are improving in specialized centers. Ethical considerations also play a crucial role in prenatal planning, including selective reduction or palliative care decisions, informed by genetic counseling for families facing conjoined twin pregnancies.

While the challenges are significant, the advancements in medical science and technology offer hope for conjoined twins and their families. The journey is fraught with risks, but with the right care and intervention, the chances of survival and leading an independent life are higher than ever before.