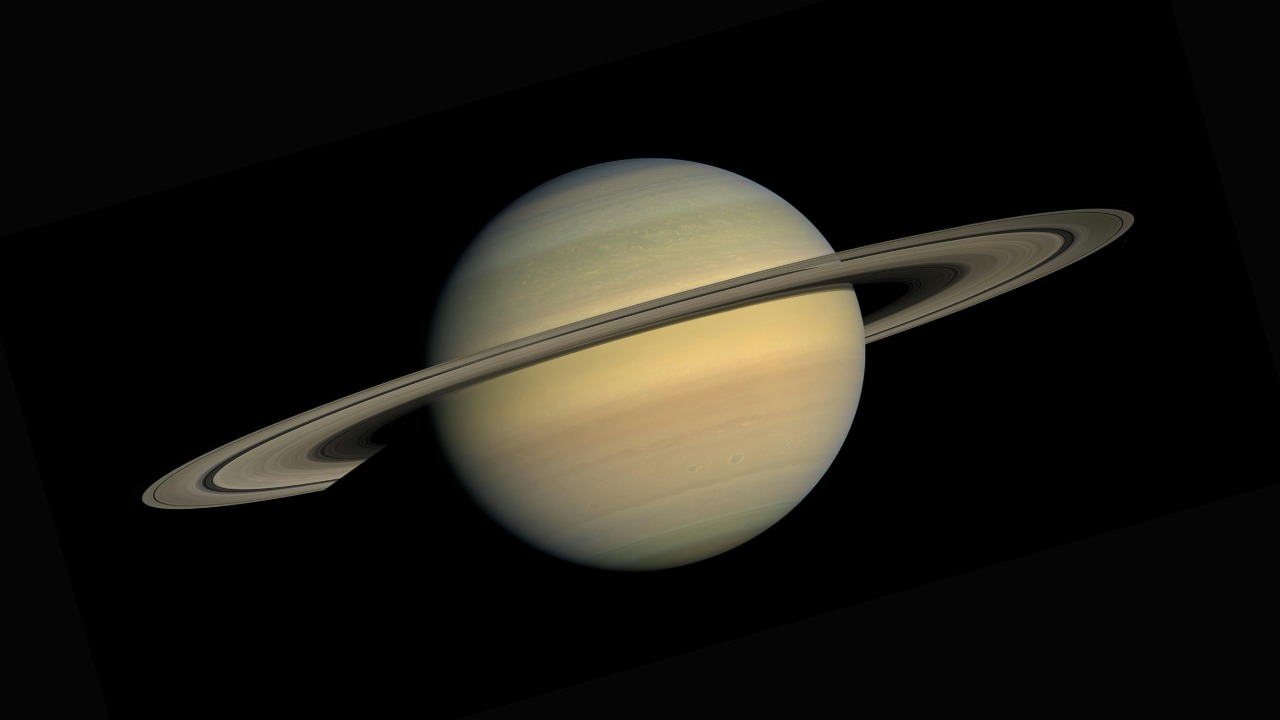

Astronomers have spotted a Saturn-sized world drifting through a region of space that theory once said should be almost empty, a so‑called Einstein desert where planets are notoriously hard to find. The discovery of this lonely giant, combined with a string of recent detections, is forcing a rethink of how common such worlds are and how far Einstein’s ideas can be pushed to map planets we can never see directly.

I see this new Saturn as part of a broader story in which gravitational tricks, next‑generation telescopes, and a few lucky alignments are turning a theoretical wasteland into one of the richest testing grounds for planetary science. From free‑floating “Rare Saturn” to a red‑hot shepherd world and a “Rare Jupiter” weighed by warped spacetime, the Einstein desert is starting to look less like a void and more like a frontier.

What astronomers mean by the “Einstein desert”

When astronomers talk about an Einstein desert, they are describing a stretch of parameter space where Einstein’s relativity should let us find planets, yet for a long time almost none showed up. The term usually refers to the gap in detections from gravitational microlensing, a method that relies on a foreground object bending and magnifying the light of a background star as predicted by Einstein’s rules for relativity. In principle, microlensing should be exquisitely sensitive to planets that are far from their stars or not bound to any star at all, but in practice the technique has delivered only a sparse handful of such worlds, leaving a desert where models expected an oasis.

The scarcity is not because the physics is fragile, but because the observational demands are brutal. To catch a microlensing event, surveys must monitor millions of stars and then react quickly when one brightens in just the right way, a process that, as one overview notes, involves searching for subtle increases in brightness caused when a massive object warps the light of a more distant star Meanwhile. For years, that combination of rarity and difficulty meant that the region of parameter space where microlensing should shine, especially for Saturn‑mass and Jupiter‑mass planets far from any star, looked almost empty, hence the evocative label.

The lonely “Rare Saturn” that broke the silence

The new Saturn‑sized planet that has captured so much attention sits right in the middle of that supposed void. Researchers have confirmed the mass of a free‑floating world nicknamed Rare Saturn, a Saturn‑sized rogue planet that drifts through space unbound to any star. The team behind the work did more than just spot a fleeting microlensing blip; they were able to pin down the planet’s actual mass, turning a transient brightening into a precise measurement of a solitary world that would otherwise be invisible.

That achievement matters because it shows that the Einstein desert is not empty, only underexplored. By catching Rare Saturn in the act of bending starlight and then modeling the event in detail, the researchers demonstrated that microlensing can weigh a Saturn‑mass object that has no host star to betray its presence. In a region of parameter space where theory predicted many such rogues but observations had found almost none, this single detection hints that the desert may be hiding a population of free‑floating giants that formed in planetary systems and were later ejected into interstellar space.

How Einstein’s spacetime trick turns darkness into data

At the heart of these discoveries is a simple but powerful idea from Einstein, that mass curves spacetime and forces light to follow that curvature. When a compact object such as a planet passes in front of a distant star, its gravity acts like a lens, briefly magnifying the star’s light in a way that depends on the mass and alignment of the lens. In the case of Rare Saturn, that fleeting magnification was the only clue that a Saturn‑sized body was there at all, yet with careful modeling of the light curve, researchers could infer both its size and its status as a free‑floating planet rather than a dim star.

The same basic principle has now been used to weigh a Rare Jupiter‑sized planet located 3,200 light‑years away, where an Astronomer used Einstein’s space‑time warping method to extract the planet’s properties from the way it distorted a background star. In both cases, the planets themselves emit almost no detectable light, yet their gravitational fingerprints on starlight are strong enough to be read from across the galaxy. That is the essence of turning darkness into data: using the geometry of spacetime as a measuring tool when photons from the object itself are out of reach.

James Webb’s Saturn‑size “shepherd” and the end of neat categories

While microlensing is filling in the Einstein desert with rogue and distant giants, the James Webb Space Telescope is rewriting expectations closer to home in parameter space. Earlier in the current exoplanet boom, James Webb spotted its first planet, a Saturn‑size “shepherd” world still glowing red hot from its formation and nestled inside a planetary ring where it appears to sculpt the surrounding debris. That object, detected as a relatively light exoplanet, shows that a Saturn‑mass body can act as an architect of its local environment, shaping rings and possibly moons while it is still shedding the heat of its birth James Webb.

That Saturn‑size shepherd is not in the Einstein desert in a strict microlensing sense, but it blurs the tidy categories that once separated “ordinary” exoplanets from the exotic rogues and distant giants found by Einstein‑based methods. The same mass range that appears in Rare Saturn and Rare Jupiter now shows up in a hot, ring‑sculpting world that James Webb can study in detail, including its temperature and atmospheric properties. For me, that overlap is crucial: it means that the physical processes inferred from one class of Saturn‑mass planets, such as how they form and migrate, can be cross‑checked against very different environments, from glowing shepherds to cold wanderers in interstellar space.

Saturn‑sized worlds around stars, and what they reveal

The Einstein desert is not only about free‑floating planets; it also touches on how often Saturn‑sized worlds appear around stars at distances where microlensing is most sensitive. One recent case that captured public imagination involved a Saturn‑Sized Alien Planet found about 110 light‑years away, a discovery that was unpacked in detail by the podcast series from We On. That world, orbiting a star rather than drifting alone, shows that Saturn‑mass planets are not rare curiosities but recurring outcomes of planet formation, turning up both in nearby systems that can be probed by transit and radial‑velocity methods and in more distant fields where microlensing dominates.

By comparing a bound Saturn‑sized planet at roughly 110 light‑years with a free‑floating Rare Saturn and a distant Rare Jupiter at 3,200 light‑years, astronomers can start to map how these giants are distributed in the galaxy. If Saturn‑mass planets are common both in close‑in orbits and as rogues, that suggests that planetary systems often form multiple giants and then dynamically reshuffle them, ejecting some into interstellar space. The Einstein desert, in that sense, becomes a record of planetary violence, a place where the survivors of gravitational skirmishes between giants can be counted and weighed.

When James Webb finds, then “loses,” a giant neighbor

The Einstein desert is also a reminder that detection is not the same as certainty. Over the summer, JWST delivered what some researchers called “the most significant JWST finding to date,” when James Webb appeared to spot a giant planet orbiting in the habitable zone of Alpha Centauri, our closest Sun‑like star. Follow‑up analysis, however, cast doubt on the signal, and the candidate world effectively vanished from the confirmed list, a sobering example of how fragile early detections can be when they push instruments to their limits JWST.

For me, that episode underscores why the Einstein desert is such a demanding proving ground. Whether the tool is microlensing, direct imaging, or transit spectroscopy, the signals are faint and the room for error is large. The same James Webb that can resolve a Saturn‑size shepherd glowing red hot can also be tripped up by noise when searching for a giant in the habitable zone of Alpha Centauri. In that context, the clean microlensing signatures of Rare Saturn and Rare Jupiter, each tied directly to Einstein’s geometric rules, look especially valuable, because they offer a different, complementary path to confidence about what is really out there.

Why measuring mass in the desert is so hard, and why it matters

Confirming that a faint lensing event is caused by a Saturn‑mass planet rather than a low‑mass star is one of the hardest tasks in exoplanet science. In the case of Rare Saturn, researchers had to disentangle the contribution of any potential host star from the microlensing light curve and then show that the lensing object’s mass fell squarely in the planetary regime. That is why the confirmation that Rare Saturn is a Saturn‑sized rogue planet, with its mass directly measured, is such a milestone: it proves that microlensing can deliver not just detections but precise planetary weights in the Einstein desert, where other methods fail.

Mass matters because it is the key to almost every other property astronomers care about, from internal structure to atmospheric retention. A Saturn‑mass rogue like Rare Saturn will have a different composition and cooling history than a more massive Rare Jupiter, even if both are free‑floating. By anchoring those differences to solid mass measurements, scientists can test models of how such planets form, whether by core accretion in a disk followed by ejection, or by direct collapse of gas in interstellar space. In that sense, every new mass measurement in the desert is not just a datapoint but a constraint on the violent histories of planetary systems across the Milky Way.

From desert to map: what comes next for Einstein’s planets

The emerging census of Saturn‑sized and Jupiter‑sized worlds found with Einstein’s spacetime tricks is still tiny, but it is already reshaping how I think about the galaxy’s architecture. With Rare Saturn, a free‑floating Saturn‑mass planet, and Rare Jupiter, a 3,200 light‑year distant giant weighed by Einstein’s space‑time warping method, astronomers now have at least two solid anchors in the Einstein desert. Add to that the Saturn‑size shepherd glowing red hot in a ring system and the Saturn‑Sized Alien Planet at 110 light‑years discussed by We On, and a pattern begins to emerge: Saturn‑mass and Jupiter‑mass planets are not confined to neat, star‑hugging orbits but are scattered across a wide range of environments.

The next steps will depend on both technology and patience. Future microlensing surveys with higher cadence and wider fields should catch more events like Rare Saturn and Rare Jupiter, while continued observations with James Webb and its successors will flesh out the properties of Saturn‑size shepherds and nearby Saturn‑Sized Alien Planets. As that catalog grows, the Einstein desert will gradually turn into a detailed map, one that shows not only where planets are now but also hints at the chaotic journeys that brought them there, guided at every step by the same curvature of spacetime that Einstein first wrote down on paper more than a century ago.

More from MorningOverview