Russia has quietly taken a bold step toward solving one of human spaceflight’s oldest problems, securing a patent for a modular spacecraft that spins to create artificial gravity for crews on long missions. The design points to a future in which astronauts are no longer confined to weightlessness for months at a time, but instead live and work in rotating habitats that mimic the pull of Earth. It is a technical blueprint, not a funded program, yet it signals how seriously Russian engineers now treat artificial gravity as the next frontier in orbit.

From patent filing to orbital ambition

The new patent sets out a vision that goes beyond a single spacecraft and into a broader architecture for living in space. Russian designers describe a system in which a central hub is paired with multiple living modules that can be rearranged, expanded, or even detached for different missions, turning the vehicle into a kind of orbital construction set rather than a fixed station. In official materials, Roscosmos is presented as the driving institutional force, with the agency credited in Dec reports as having secured protection for a rotating space station concept that would generate artificial gravity by spinning its inhabited sections in orbit, a move that underscores how seriously it now treats long duration human presence away from Earth’s surface as a strategic goal, as highlighted in one detailed Roscosmos patent.

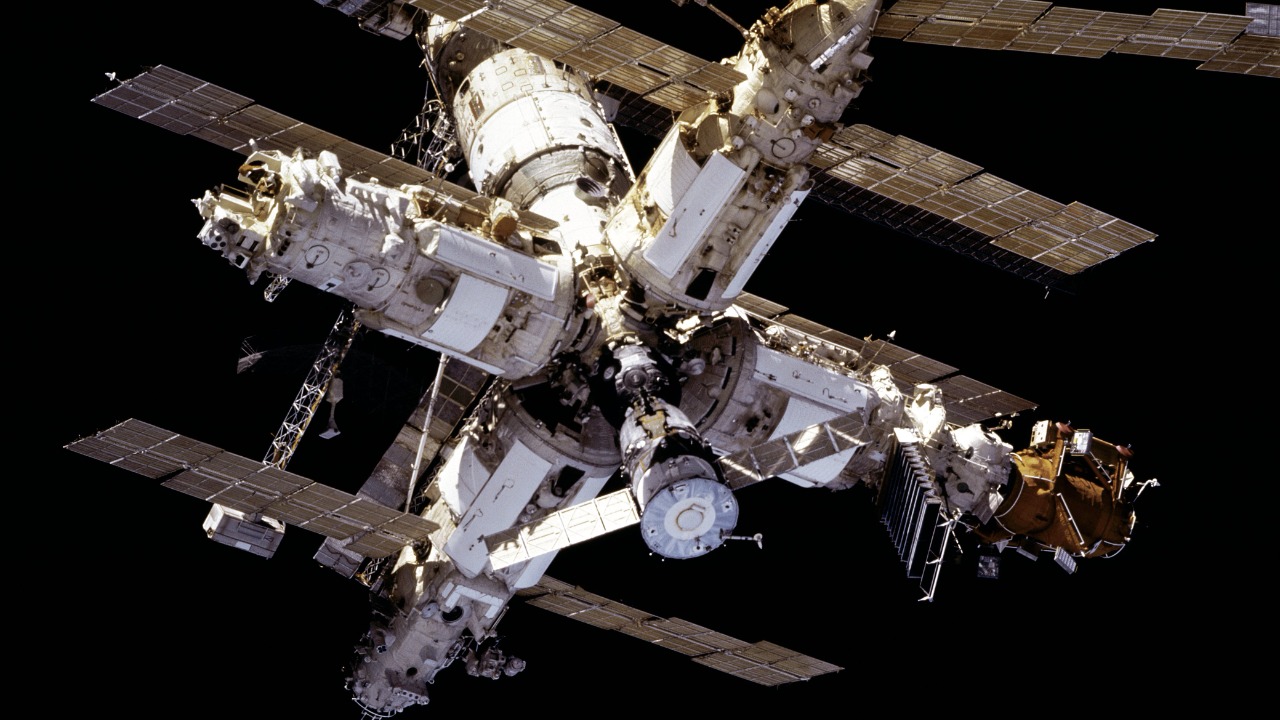

Visuals released alongside the patent show a spacecraft that looks less like the familiar stick-like International Space Station and more like a wheel in the making, with a solid core and radial arms that can host pressurized modules. In coverage titled Russia Unveils Rotating Space Station for Artificial Gravity, the design is described as a rotating station that uses its spin to create a sense of weight on the floor, a concept that has lived in science fiction for decades but has rarely been pursued at scale in real hardware. By locking this idea into a formal patent, Russian engineers are not just sketching a thought experiment, they are staking a claim on a specific configuration of modules, joints, and rotation systems that could shape how future orbital habitats are built.

How the modular, rotating design is supposed to work

At the heart of the patent is a simple but powerful mechanical idea, a central axis that does not rotate, surrounded by living modules that do. The documents describe a main body that stays relatively stable in orientation, with radially attached habitable sections that are spun around this core to generate centrifugal force, so that the outer walls of each module effectively become the “floor” under the crew’s feet. One detailed breakdown notes that the radially attached habitable modules would be rotated around this central body to create a controllable level of artificial gravity, a configuration that is explicitly laid out in the patent description and that would let engineers tune the spin rate to simulate anything from lunar to near Earth gravity.

To make this rotation possible without compromising life support, the patent specifies a hermetically sealed, flexible junction between the spinning modules and the non rotating core, a kind of rotating joint that must carry air, power, data, and fluids while still allowing the outer ring to turn. Reports on the filing explain that Russia’s design calls for these habitable modules to be connected to the central body through such a sealed, flexible junction, a detail that appears in technical coverage of how Russia patents the station’s rotating interface. In practice, this would make the spacecraft modular in more than name, since additional living sections could be added like spokes on a wheel, or individual modules could be swapped out for specialized laboratories or medical bays without redesigning the entire structure.

Artificial gravity as a response to microgravity’s toll

The motivation behind this rotating architecture is not aesthetic, it is medical. Dec reporting on the patent repeatedly stresses that Russia is targeting one of the most stubborn problems in human spaceflight, the way long exposure to microgravity erodes bones, weakens muscles, and strains the cardiovascular system despite rigorous exercise regimes. In one analysis, artificial gravity is described as the glue that holds the human body together, with the rotation of a station pushing astronauts toward the floor with centrifugal force so that their skeletons and hearts experience something closer to the constant load they evolved under on Earth, a point made explicitly in coverage that notes how gravity is the glue that keeps astronauts healthy.

Russian sources frame the new patent as a direct attempt to protect astronaut health during long stays in orbit, positioning the rotating modules as a kind of in built countermeasure to the physiological decline that has plagued crews on the International Space Station. One Dec summary notes that Russia plans a rotating space station with artificial gravity specifically to protect astronaut health, linking the concept to a broader strategy for future missions that might last far longer than current six month tours. That same report explains that while the International Space Station prepares for a watery end, Russia is looking up and spinning, a vivid phrase used to describe how the country is pivoting from the aging ISS to a new generation of habitats that rely on rotation rather than constant free fall, as detailed in coverage of how Russia plans rotating stations.

A concept tailored for the post ISS era

The timing of the patent is not accidental. Russian officials have already agreed to keep flying crews aboard the International Space Station until 2028, but they also know that the platform is approaching the end of its life and that a replacement will be needed if the country wants to maintain a permanent human presence in orbit. One Dec analysis of the filing notes that the patent indicates a clear interest in artificial gravity at a moment when the end of the Internati era is in sight, and it explicitly states that Russia has committed to keep its cosmonauts aboard the ISS until 2028, a detail that appears in a report on how the patent does however indicate a bridge between the current station and whatever comes next.

In that context, the rotating modular spacecraft looks less like a speculative sketch and more like a candidate for a post ISS flagship. Coverage of the filing describes it as a concept to generate artificial gravity in orbit for long duration missions, explicitly linking it to a future post ISS era in which Russia would need its own independent platform. One detailed breakdown even labels the design as Russia Patents Rotating Space Station Concept to Generate Artificial Gravity in Orbit, and notes that it is framed as a way to support long duration missions in a future post ISS era, language that appears in a report on how Russia Patents Rotating Space Station Concept as a strategic move. The implication is that Moscow wants to ensure it has a technically distinctive answer ready when the ISS is finally deorbited.

Energia’s role and the realities of funding

Behind the patent’s diagrams sits a familiar industrial player, the Russian state rocket company Energia, which has built much of the country’s human spaceflight hardware since the Soviet era. Dec coverage of the rotating station notes that Energia has officially secured a patent for a modular space station that can rotate its living modules to generate artificial gravity during a long term stay, tying the design directly to the company’s engineering base and its long experience with vehicles like Soyuz and Progress. In the same report, Energia is described as the Russian state rocket company that is now positioning itself at the center of a new space race focused on human health and comfort in orbit, a role spelled out in the detailed account of how Patent for artificial gravity stations is tied to Energia’s portfolio.

Yet even the most enthusiastic reports acknowledge that the patent is not a construction contract. Analysts note that there are currently no resources or timelines attached to the rotating station, and that Russia has not committed the kind of multi year funding that would be needed to turn the drawings into metal. One Dec summary of the filing points out that although Energia has secured the patent and Russia is actively exploring a rotating space station concept, there are no concrete resources to back its development yet, a caveat that appears in coverage of how the radially attached modules would be rotated around the central body but that also stresses the absence of a firm budget or schedule in the Mortgage Rates Fall Off era of tight spending. For now, the design lives on paper, a marker of intent rather than a guaranteed destination.

Deep space ambitions: Mars, Moon, and beyond

Even if the first application of the rotating modules is likely to be in low Earth orbit, Russian sources are already talking about how the same architecture could support missions much farther from home. One Dec report notes that Russia is actively exploring a rotating space station concept designed to generate artificial gravity as a way to support future missions to Mars or deep space, explicitly linking the patent to interplanetary ambitions rather than just an ISS replacement. In that account, the rotating modules are framed as a way to keep crews healthier on journeys that could last many months, a point made in a summary that describes how Russia is actively exploring artificial gravity for Mars or deep space.

Other Dec coverage echoes this framing, describing the patent as a rotating space station concept designed to generate artificial gravity by spinning its living modules, with the explicit aim of protecting astronauts during long duration missions that might include flights to Mars. One widely shared summary notes that Russia has patented a rotating space station concept designed to generate artificial gravity by spinning its living modules, and that this is presented as a way to protect astronauts on long duration missions, language that appears in a report explaining how Russia has patented the concept. In that sense, the modular spacecraft is not just a new kind of station, it is a testbed for the kind of spinning habitats that many mission planners believe will be essential if humans are ever to travel comfortably to Mars and back.

Technical challenges of spinning a space station

Turning the patent into a working spacecraft will require solving a series of difficult engineering problems that go far beyond drawing a wheel in orbit. The rotation rate must be carefully chosen so that the artificial gravity is strong enough to help the body but not so intense that it causes motion sickness or dangerous structural loads, and the radius of the rotating modules must be large enough to keep the Coriolis effects tolerable when astronauts move their heads or limbs. The patent’s emphasis on radially attached habitable modules that can be rotated around a central body hints at this balancing act, since a larger radius allows for a slower spin to achieve the same effective gravity, a relationship that is implicit in the technical description of how centrifugal force would push astronauts toward the floor.

On top of that, the hermetically sealed, flexible junctions between the rotating and non rotating sections must be robust enough to operate for years without leaks or mechanical failure, a challenge that has no direct precedent at the scale envisioned in the patent. Reports on the filing highlight that the modules would be connected to the central body through such sealed, flexible junctions, and that this is a key innovation in the design, since it allows the station to maintain a stable core for docking and control while still spinning its living quarters. One detailed account of the patent explains that Russia’s design calls for habitable modules connected by a hermetically sealed, flexible junction, a feature that is spelled out in the technical description of how Russia patents the rotating interface. Getting that joint right will be essential if the modular spacecraft is ever to move from patent drawings to a launch pad.

How the concept fits into Russia’s broader space strategy

The rotating modular spacecraft does not exist in a vacuum, it fits into a broader Russian strategy that seeks to maintain national prestige in orbit while adapting to a rapidly changing space landscape. Dec reports emphasize that Russia has patented a rotating spacecraft design that could create artificial gravity for long duration space missions, and that this is presented as part of a wider effort to prepare for a future in which the ISS is gone and new commercial and national stations compete for crews and contracts. One detailed summary notes that Russia has patented a modular spacecraft designed to create artificial gravity, and that the filing does not yet include a timeline for building the system, a point made in coverage explaining how Russia has patented a modular spacecraft without committing to dates.

At the same time, other Dec accounts stress that Russia has already patented a rotating space station concept designed to generate artificial gravity, and that this is being framed domestically as a sign that the country is still capable of bold technical innovation despite budget pressures and geopolitical tensions. One widely shared report notes that Russia has patented a rotating space station concept designed to generate artificial gravity by spinning its living modules, and that this is being promoted as a way to protect astronauts on long duration missions and to keep Russia competitive in a new space race focused on human health and comfort, language that appears in a summary of how Russia has patented the rotating station. Whether the modular spacecraft ever flies or not, the patent itself has already become a symbol of Russia’s determination to shape the next chapter of human life in orbit.

More from MorningOverview