Across the sky, brief and violent flashes of energy are arriving from far beyond the Milky Way, each one lasting less than the blink of an eye yet outshining whole galaxies. These rare bursts, from radio waves to gamma rays, are forcing astronomers to rethink how some of the universe’s most extreme objects behave. I see a field that once thought it had a tidy explanation now racing to keep up with a cosmos that keeps refusing to play by simple rules.

The puzzle is not just that these eruptions are powerful, but that they are inconsistent, sometimes repeating, sometimes silent, and often emerging from places where theory said they should not exist. As more telescopes catch them in real time, the hunt has shifted from merely logging their arrival to tracing each flash back to its home environment and the exotic engines that light it up.

Fast radio bursts break out of their comfort zone

For years, the leading idea was that most fast radio bursts, or FRBs, came from highly magnetized stellar remnants called magnetars, the compact corpses left behind after supernova explosions. That picture fit early detections that seemed tied to young, star forming regions where such magnetars should be plentiful, and it gave theorists a clean way to connect intense magnetic fields to millisecond radio flashes. The neatness of that story is now under strain as new events refuse to line up with expectations.

One of the sharpest challenges arrived when Feb and other researchers traced an FRB, cataloged as FRB 20240209A, to what they described as a “dead” galaxy with little ongoing star formation, a place where fresh magnetars should be rare. The blast from FRB 20240209A did not just stretch the magnetar model, it suggested that either old stellar populations can somehow still produce these engines or that an entirely different kind of object can mimic their radio signatures. I read that as a warning that any single origin story for FRBs is likely to be incomplete.

Clues from chaotic neighborhoods and pinpointed hosts

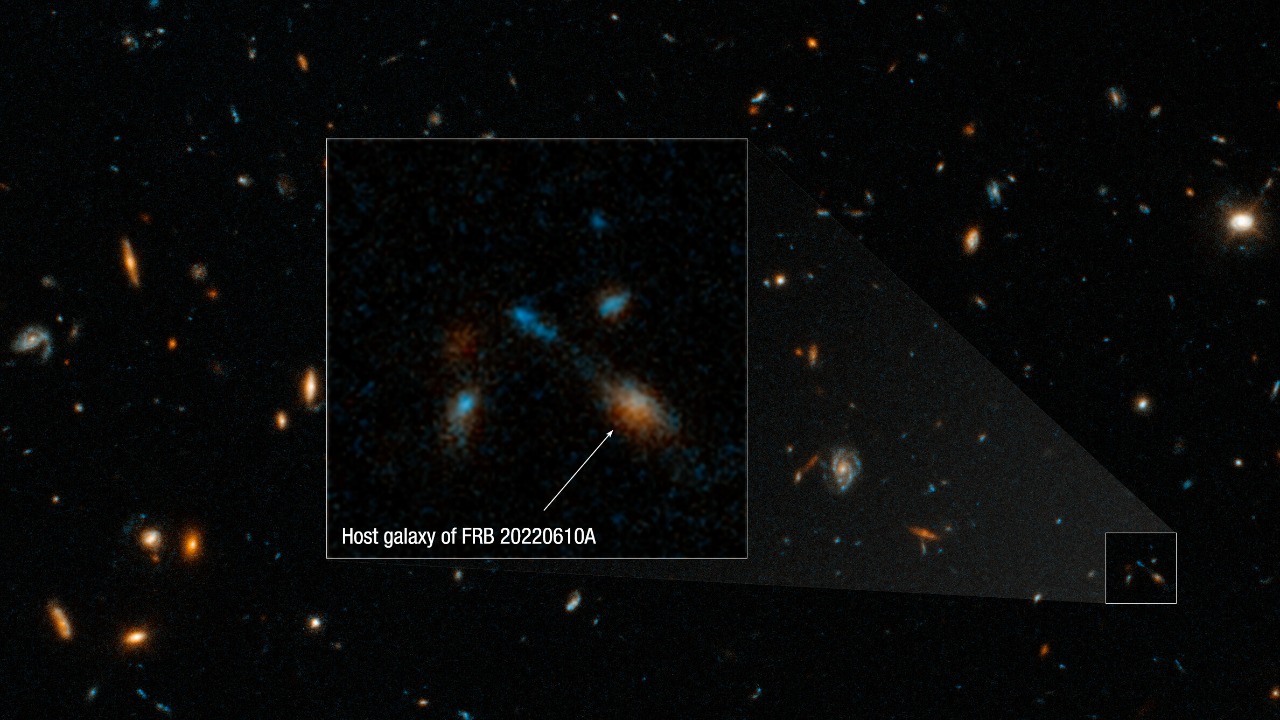

As more instruments come online, the emerging pattern is not of a single culprit but of a diverse cast of extreme environments that can all generate similar looking radio spikes. Jan and colleagues have highlighted one FRB that appears to come from the turbulent region around a dense neutron star, where magnetic fields twist and reconnect in a chaotic dance. That event, set against a backdrop of thousands of FRBs logged since 2020, hints that some bursts may be powered by interactions in crowded stellar neighborhoods rather than isolated magnetars alone, a point underscored by One of the the best studied cases.

Improved timing and localization are sharpening that picture even further. Jan and a team using radio arrays have shown that with sub arcsecond precision, optical telescopes can swing into action and identify whether a burst came from a globular cluster, a spiral arm, or some other distinct structure. In at least one case, the FRB appears linked to a globular cluster, a dense ball of ancient stars that should not be churning out young magnetars at all. That kind of association, made possible by new precision, points to either recycled neutron stars or exotic binaries as alternative engines, and it reinforces the idea that FRBs are a phenomenon, not a single class of object.

Exotic stellar corpses and mysterious repeaters

Even as FRB hunters broaden their search, other telescopes are catching different kinds of bursts that may share some underlying physics. One main suspect for the source of FRBs is magnetars, rapidly spinning neutron stars with the most powerful magnetic fields known, and those same fields can twist space around them in ways that also produce X rays and gamma rays. Theorists have argued that sudden shifts in those fields could crack a magnetar’s crust, releasing energy that cascades into radio waves, a scenario that fits several events described in Aug reports.

Yet some objects refuse to be pigeonholed even as magnetars. A celestial source about 15,000 light years away has been caught firing off bright flashes of both radio and X rays, with a pattern and energy output that do not match standard pulsars or known magnetars. The team tracking this 15,000 light year enigma has struggled to explain how it launches its signals, and I see that ambiguity as part of a broader theme: the more closely we watch compact objects, the more hybrid behaviors we find that blur the lines between categories like pulsar, magnetar, and something new.

Gamma ray tempests and black hole feasts

At even higher energies, gamma ray observatories are catching their own share of record breaking outbursts that complicate the story of cosmic explosions. Gamma ray bursts, or GRBs, are already known as some of the most powerful events in the universe, typically tied to the collapse of massive stars or the merger of compact objects. When a recent event labeled GRB 250702B lit up detectors for roughly 7 Hours of Fury, with Astronomers Detect GRB describing it as the Largest Gamma Ray Burst Ever Observed, it stretched models of how long a single engine can sustain such an intense beam, as highlighted in Gamma focused coverage.

Not all extreme bursts come from clean, one off explosions. Jan brought fresh attention to a so called Super star being torn apart by a black hole, a tidal disruption event that releases as much energy as 400 billion suns as stellar material spirals inward. In that case, the shredded star appears to feed parallel jets that channel energy into space, a process that can generate both X rays and gamma rays over extended periods. The sheer scale of that 400 billion sun equivalent output shows how black holes can power long lasting flares that rival or exceed classic GRBs, and it hints that some of the most dramatic bursts we see may be the visible edge of a much longer feeding frenzy.

Einstein Probe’s “weird explosion” and what comes next

Even with these examples, some events still defy easy classification, and those are often the ones that push theory forward the fastest. Astronomers using the Einstein Probe spacecraft reported a “weird explosion” that did not match the usual signatures of a standard GRB or a simple flare from an active galaxy. The transient, spotted in April of the previous year, left teams debating whether they were seeing the aftermath of a black hole suddenly switching on, a new kind of jet, or something that only partly overlaps with known categories, a debate captured in early Einstein Probe analyses.

From my vantage point, the common thread running through FRBs, magnetar like objects, record setting GRBs, tidal disruption events, and Einstein Probe’s oddball explosion is that each new detection chips away at the idea that there is a single “standard candle” for any of these bursts. Instead, the universe seems to offer a spectrum of engines that can all, under the right conditions, unleash brief torrents of energy across the electromagnetic range. As more facilities coordinate across wavelengths and as localization sharpens, I expect the race to find the sources of these rare bursts to evolve into something more ambitious: a systematic map of how extreme gravity, magnetic fields, and dense matter conspire to light up the sky in ways we are only beginning to decode.

More from Morning Overview