Biologists have long treated the cell as a chemical factory, but a new wave of research is forcing a rethink of that familiar picture. Instead of just tiny bags of reacting molecules, our cells appear to be threaded with subtle electrical structures that shape how energy moves, how cancers grow, and how aging unfolds. The emerging idea is simple but radical: there may be a hidden layer of power around and within our cells that we have barely started to measure, let alone control.

That shift is not happening in a vacuum. From intricate models of flickering membranes to glowing “energy halos” around tumor cells and experimental attempts to recharge worn-out tissues, several teams are converging on the same theme. I see a field that is starting to treat electricity as a first-class player in biology, not just a side effect of chemistry, and that change could eventually alter how we think about everything from cancer drugs to longevity therapies.

The quiet revolution in cellular electricity

For decades, textbooks have framed cellular energy almost entirely in chemical terms, with mitochondria converting nutrients into ATP and everything else downstream of that fuel. What is taking shape now is a more layered view, where electrical gradients, local voltages, and dynamic charge distributions are not just byproducts but active components of how cells work. Instead of a single “battery” in the mitochondrion, I now have to picture a network of tiny power fields that can switch on and off as cells divide, migrate, or age.

That shift is clearest in work that tracks previously unknown electrical behavior inside cells, where researchers have shown that the powerhouses of our cells, the mitochondria, generate energy through the same basic chemistry we already teach, yet also sit inside a landscape of charged condensates and structures that may help route that power. In one set of experiments, scientists argued that this intracellular electricity could be important to many different fields, from neurobiology to toxicology, and asked why not condensates instead of membranes should be treated as key electrical players, a line of reasoning captured in a report on previously unknown intracellular electricity.

A hidden source of power around our cells

Alongside that internal circuitry, other teams are now arguing that there is a distinct, overlooked source of power sitting at the very edge of the cell. Instead of focusing only on the familiar voltage across the membrane, they have modeled how the membrane itself, with its constant thermal and active fluctuations, can generate measurable electrical effects. In this view, the cell surface is not just a passive barrier but a dynamic, vibrating interface that can convert motion into charge separation.

One group, led by Pradeep Sharma and colleagues, created a model showing that active biological processes, such as protein dynamics in the membrane, can drive these fluctuations strongly enough to generate transmembrane voltages that reach 90 millivolts, a level that is comparable to what neurons use to fire. Their work on how cell membrane fluctuations generate electricity suggests that the very act of being alive, with proteins jostling and reshaping the membrane, may constantly recharge a subtle electrical layer around each cell.

From theory to “energy halos” around cancer cells

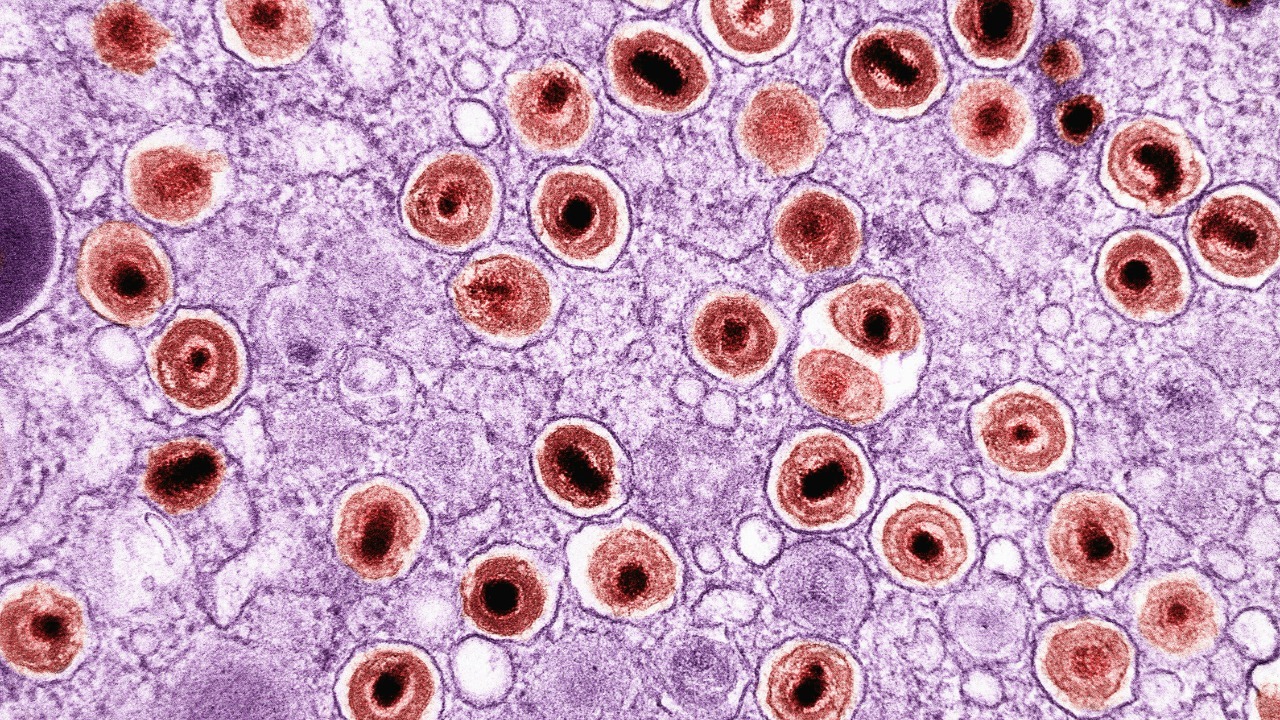

The idea of a powered cell surface might sound abstract until you see what happens when cancer cells are pushed into extreme conditions. Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation, or CRG, in Barcelona used specialized microscopy to watch tumor cells as they were compressed, mimicking the crowded environment inside a growing mass. Under that mechanical stress, the mitochondria did something striking: they moved and clustered into a dense, glowing ring around the nucleus, so intense that it physically indented the nuclear envelope.

In that configuration, the cells’ energy production did not just hold steady, it surged. The discovery of these NAM Energy Halos, named for the specific metabolic state involved, showed that when mitochondria form this ring, the energy output increased by about 60 percent compared with more relaxed cells. The team reported that scientists at the Centre for Genomic Regulation saw this effect only in compressed cells and none in floating, uncompressed cells, a pattern described in detail in a report on the Discovery of NAM Energy Halos.

How cancer “powers up” under pressure

Those halos are not just pretty images, they are a clue to how tumors exploit their environment. When cells are squeezed inside a solid mass, they face limited nutrients and oxygen, yet cancers often thrive in exactly those conditions. By clustering mitochondria into a ring, the cell seems to create a local power belt around its genetic material, potentially protecting the nucleus and fueling rapid division even when resources are scarce. I see that as a kind of emergency overdrive mode, triggered by mechanical stress rather than a simple chemical signal.

Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona went further and showed that this power-up state could be switched off. By targeting the pathways that drive mitochondrial clustering, they were able to disrupt the formation of the ring and blunt the energy surge, pointing to a possible new way to weaken tumors that rely on this trick. Their work, which described how compressed cancer cells formed these halos while none appeared in floating, uncompressed cells, framed the phenomenon as cancer’s “power-up” and outlined a strategy to interrupt it, as detailed in a study on how Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation uncovered and then switched off this effect.

Voltage at the membrane: a new biological control knob

While the halos highlight how energy can be reorganized inside the cell, other work is focusing on the voltage that sits across the membrane itself. That voltage is already known to guide nerve impulses and muscle contractions, but the new modeling suggests it may also be tuned by the physical state of the membrane, not just by ion channels opening and closing. If fluctuations can push the transmembrane voltage toward 90 millivolts, as Pradeep Sharma and colleagues calculated, then any process that stiffens or loosens the membrane could, in principle, change how power flows into and out of the cell.

That idea is echoed in reports that describe a hidden source of power surrounding our cells, where the voltage produced could assist in the movement of ions, the charged atoms that are controlled by the flow of electricity. In those accounts, the voltage is not a static number but a dynamic quantity that may vary as expected inside the body, rising and falling with activity and potentially influencing how signals propagate through tissues. One summary of this work noted that the voltage produced could assist in the movement of ions and might behave differently inside living organisms than in simplified lab systems, a point captured in coverage of how the voltage produced could assist in ion transport around cells.

Recharging aging cells with fresh mitochondria

If cancer shows what happens when cells push their energy systems into overdrive, aging reveals the opposite problem: power plants that sputter and fail. As mitochondria accumulate damage, tissues lose resilience, and organs become more vulnerable to stress. Instead of trying to tweak those failing structures in place, some scientists are now testing a more direct approach, transplanting healthy mitochondria into tired or injured cells to see if they can be revived. It is a literal attempt to recharge biology by swapping out the batteries.

Researchers at Texas A&M have reported that they can revive tired or damaged cells by giving them a fresh supply of mitochondria, restoring their energy and resilience in the process. In their experiments, cells that had been pushed into a low-energy state began to function more normally once the new organelles were in place, suggesting that at least some aspects of aging and injury are reversible if the energy machinery can be reset. The work, which described how Researchers at Texas found a way to recharge aging cells, fits neatly into the broader picture of cells as systems whose electrical and chemical power supplies can be actively managed.

Connecting intracellular fields to whole-body health

What ties these threads together is the realization that energy in biology is not just about how much ATP a cell can make, but where and how that energy is organized in space. The NAM Energy Halos around cancer nuclei, the fluctuating voltages across membranes, and the rejuvenated mitochondria in aging cells all point to a world where local electrical environments matter. I see a future in which doctors might talk about restoring healthy voltage patterns in tissues the way they now talk about correcting hormone levels or blood pressure.

That vision is still speculative, and it depends on turning qualitative images and models into quantitative tools. The work on previously unknown intracellular electricity, which highlighted how the powerhouses of our cells operate within a broader electrical context, and the modeling that showed how cell membrane fluctuations can generate electricity, both suggest that basic physics can be used to predict and eventually manipulate these fields. At the same time, the reports on a Hidden Source of Power May Have Been Discovered Surrounding Our Cells and on ways to recharge aging human cells hint at clinical applications, from slowing degenerative diseases to designing drugs that target the power-up modes of tumors.

What comes next for the science of cellular power

For now, the most immediate impact of this research is conceptual. It forces biologists, clinicians, and even engineers to think of cells as electromechanical systems, where forces, shapes, and charges are intertwined. I find that shift particularly important for fields like cancer biology, where mechanical stress, metabolic rewiring, and genetic instability all collide. The discovery that compressed tumor cells can assemble a mitochondrial ring that boosts energy by about 60 percent, and that this state can be switched off, gives drug developers a concrete new target that sits at the intersection of mechanics and metabolism.

On the aging side, the demonstration that fresh mitochondria can restore energy and resilience to tired cells suggests that at least some age-related decline is not a one-way street. Combined with the growing evidence that intracellular electricity and membrane-generated voltages shape how ions move and how signals propagate, it points toward a future in which therapies might aim to reset the electrical environment of tissues as much as their chemistry. The science is still young, and many details remain unverified based on available sources, but the core message is already clear: there is more power in and around our cells than we once imagined, and learning to read and rewrite that hidden circuitry could become one of the defining challenges of twenty-first century medicine.

More from MorningOverview