Long before anyone wrote down a number, early villagers were painting flowers with a precision that looks suspiciously like mathematics. Recent analysis of 8,000‑year‑old botanical designs suggests that people in small farming communities were already thinking in terms of symmetry, repetition, and structure, even if they had no formal symbols for counting. The patterns are turning fragile shards of pottery into evidence that numerical reasoning quietly shaped daily life far earlier than written records imply.

Instead of treating these decorations as simple ornament, researchers are now reading them as a record of a cognitive shift that came with settled village life. The way branches, shrubs, and blossoms are arranged hints at an emerging sense of geometric order, where beauty and balance are guided by rules that look a lot like hidden math.

Ancient flowers, modern questions

When I look at the new research on prehistoric floral art, what stands out is not just that the designs are pretty, but that they are disciplined. Over 8,000 years ago, early villagers were already arranging flowers, shrubs, branches, and trees in ways that repeat, mirror, and rotate with striking regularity. That kind of visual control is hard to explain as random doodling, especially when it appears again and again on fine pottery rather than on disposable surfaces.

The work focuses on carefully preserved ceramics whose botanical motifs are laid out with consistent spacing and mirrored halves, suggesting that the artists were following internal rules about balance and proportion. Researchers argue that this reflects a cognitive shift tied to village life and a growing awareness of symmetry and aesthetics, a shift that points to an underlying sense of geometric structure and numerical order even before explicit number systems existed, as detailed in the study of 8,000‑year‑old art.

From decoration to data

For a long time, archaeologists treated these floral motifs as background noise, the decorative fringe around the “real” evidence of early civilization. I see the new analysis as a reversal of that hierarchy. Instead of assuming that art is secondary, researchers are treating each petal and branch as data points that reveal how people organized space in their minds. The repetition of specific counts of leaves or the consistent pairing of stems becomes a clue to how early artists thought about grouping and pattern.

By cataloging how often certain motifs appear, and how they are arranged relative to one another, scholars can test whether the designs follow simple visual habits or more systematic rules. When the same flower appears with four petals in one context and eight in another, but always in balanced layouts, it suggests that the artist was comfortable manipulating quantities and symmetries. In that sense, the pottery becomes a kind of visual ledger of cognitive habits, showing that numerical thinking can be embedded in decoration long before it is written down.

Village life and the rise of symmetry

The timing of these designs matters. They emerge in communities that had shifted from mobile foraging to settled village life, where people were storing grain, managing herds, and coordinating shared spaces. I find it telling that the same period that demanded more planning and record‑keeping also produced art that is more structured and symmetrical. When daily survival depends on tracking seasons, harvests, and property boundaries, it is not surprising that minds start to favor order over improvisation.

Researchers argue that this new preference for symmetry and repeated motifs reflects a broader cognitive reorganization that came with permanent houses and communal storage. The neat rows of petals and mirrored branches on pottery echo the neat rows of crops and the regular layout of village streets. In that reading, the art is not just decorative, it is a visual echo of a world that had become more gridlike and predictable, where people were learning to trust patterns and to see beauty in regularity.

Hidden Numeri and the logic of pattern

One of the most intriguing ideas to emerge from this work is the notion of “Hidden Numeri,” the idea that numerical thinking can be present in a culture without explicit numerals or arithmetic notation. I interpret Hidden Numeri as a way to describe the quiet logic that governs how many times a motif repeats, how elements are grouped, and how symmetry is enforced. The artists may never have said “four” or “eight” out loud, but their hands still divided space into equal parts and their eyes still checked for balance.

In the 8,000‑year‑old floral designs, Hidden Numeri shows up in the consistent use of even counts of petals, the pairing of branches, and the rotational symmetry of circular motifs. These are not random choices. They require the artist to keep track of how many elements have already been painted and how many remain to complete the pattern. That mental bookkeeping is a form of proto‑mathematics, a bridge between intuitive perception and formal number systems that would only appear much later in written form.

Fine pottery as a mathematical canvas

The level of care invested in these objects also matters. The floral motifs in question are not scratched onto rough storage jars, they appear on fine pottery that required skill to shape and fire. I read that as a sign that the patterns were socially meaningful, perhaps tied to status, ritual, or identity. When a community reserves its most precise, symmetrical designs for its most valued objects, it is effectively elevating mathematical order as a marker of quality and prestige.

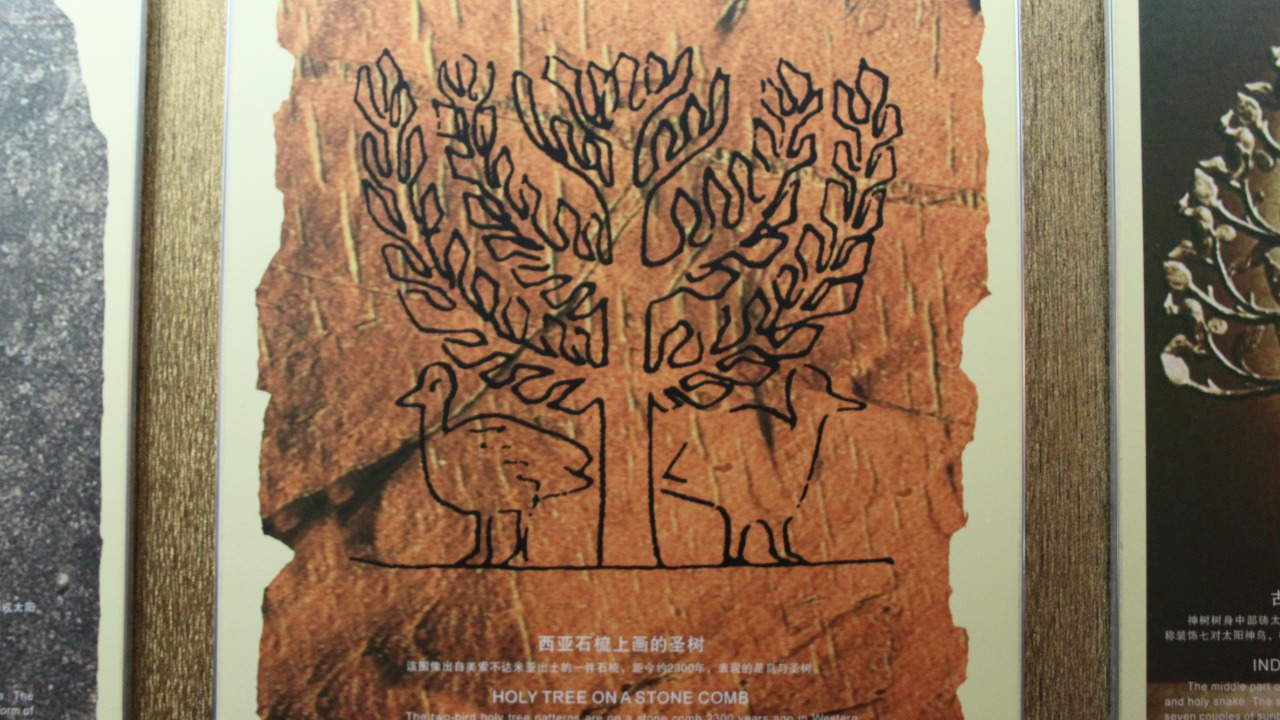

Researchers studying this fine pottery report that the flowers, shrubs, branches, and trees are arranged with careful symmetry and repeating units, and that the Halafian‑style pieces in particular show that these arrangements were not random but reflected underlying mathematical structure. The fact that the Halafian ceramics combine botanical imagery with such disciplined repetition suggests that early artists were comfortable weaving numerical order into scenes drawn from nature, as highlighted in the analysis of Halafian fine pottery.

Nature as a template for early geometry

What makes botanical art such a powerful window into early math is that plants themselves are full of patterns. Leaves spiral around stems, petals radiate from centers, and branches fork in regular ways. When I compare the ancient motifs to real flowers and shrubs, it is clear that the artists were not copying nature exactly, they were stylizing it. They simplified complex forms into repeated units, straightened curves into lines, and turned irregular clusters into evenly spaced arrays.

That act of stylization is a kind of geometric thinking. To turn a messy branch into a clean, mirrored motif, an artist has to decide which features matter and which can be ignored. The result is a design that captures the “rule” of the plant rather than its literal appearance. In doing so, the artist is already thinking like a geometer, abstracting from the world to create a pattern that can be repeated, rotated, and combined with others without losing its identity.

Math before numerals

The absence of written numbers in these communities has often been taken as evidence that they lacked mathematical sophistication. I see the floral art as a direct challenge to that assumption. Counting, grouping, and comparing quantities do not require numerals, they require consistent mental operations that can be expressed in many ways, including through visual pattern. When an artist repeats a motif exactly six times around a bowl, that is a counting act, even if no symbol for “6” exists.

These designs suggest that early villagers were already comfortable with concepts like parity (even versus odd), proportionality (keeping petal sizes and gaps consistent), and perhaps even simple ratios (such as maintaining a two‑to‑one relationship between different elements in a border). All of this can happen in the mind and in the hand without ever touching clay tablets or ink. The math is there, embedded in the rhythm of the pattern, waiting for modern analysts to decode it.

What this changes about human cognitive history

Placing hidden mathematical structure inside 8,000‑year‑old art forces a rethink of when and how numerical reasoning emerged. Instead of treating math as a late invention that arrived with bureaucrats and scribes, I now see it as a gradual outgrowth of everyday tasks and aesthetic choices in small communities. The villagers who painted these flowers were not mathematicians in any formal sense, yet their work shows that they were already comfortable organizing the world into repeatable, countable units.

This perspective also softens the boundary between practical and abstract thought. The same mind that tracks how many jars of grain are in a storehouse can also enjoy the satisfaction of a perfectly balanced border of petals. By reading early botanical art as evidence of Hidden Numeri, researchers are arguing that the roots of mathematics lie not only in accounting and astronomy, but also in the quiet pleasure of making a pattern come out just right.

More from MorningOverview