Researchers have unveiled a way to flip genes back on without slicing into the genome, a shift that could make CRISPR far safer and more flexible. Instead of cutting DNA, the new approach scrubs away chemical tags that keep genes silent, turning them back into active instructions inside the cell. It is a technical refinement with sweeping implications, from inherited blood disorders to how we think about editing the human genome at all.

By treating gene activity like a dimmer switch rather than a demolition job, scientists are starting to separate CRISPR’s power from its most worrisome risks. The work builds on earlier efforts to control gene expression with precision tools, but it goes further by directly reversing the epigenetic marks that lock genes in the “off” position.

From cutting DNA to cleaning chemical tags

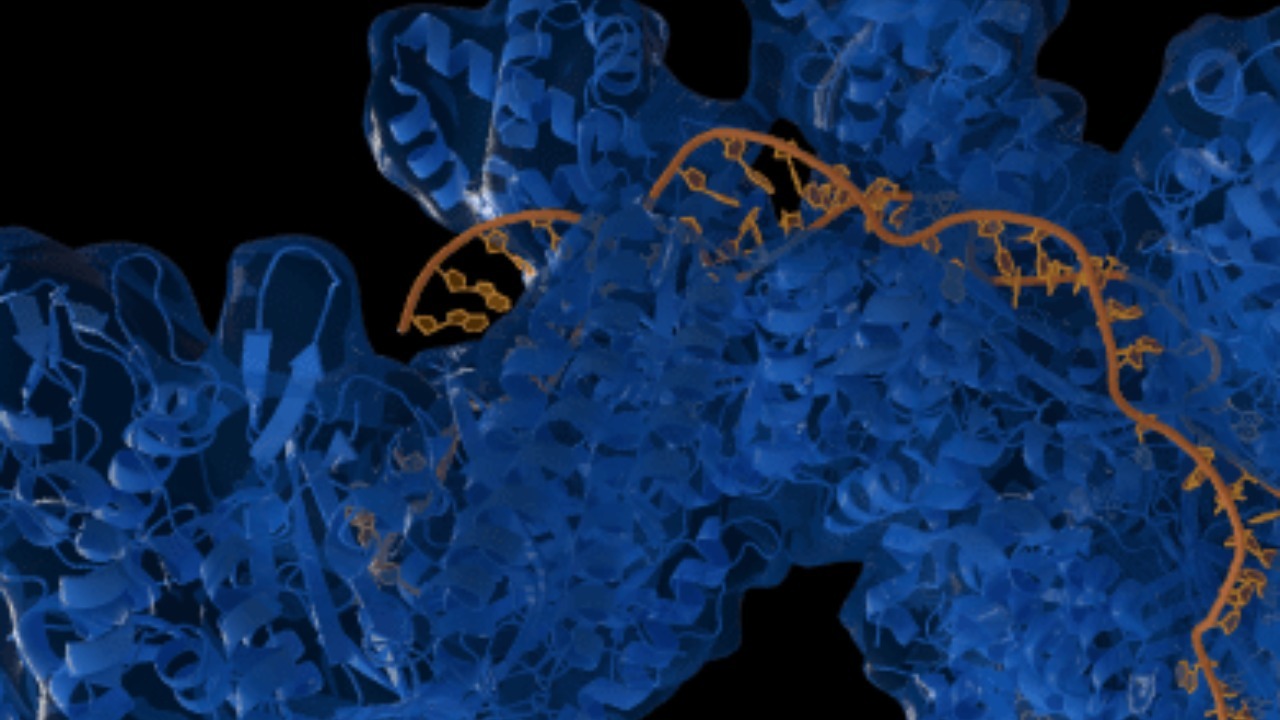

The original CRISPR systems were built to cut, relying on molecular scissors that slice through DNA to disable or rewrite genes. That strategy has already transformed experimental medicine, but every cut carries a chance of unwanted mutations, rearrangements, or broken chromosomes that the cell repairs imperfectly. The new technique keeps the CRISPR targeting machinery but swaps out the blade for an eraser, focusing on the chemical tags that sit on DNA and its packaging proteins and that tell a cell which genes to ignore.

In the latest work, scientists use CRISPR to home in on specific stretches of DNA, then remove the epigenetic marks that had shut those genes down, effectively turning them back on without altering the underlying sequence. The study describes how these chemical tags can be stripped away so that dormant genes start producing RNA and protein again, a process that one report describes as a new CRISPR breakthrough that turns genes on without cutting DNA. By decoupling gene activation from DNA damage, the method reframes what “editing” can mean in human cells.

Why turning genes on matters as much as turning them off

Most early CRISPR therapies have focused on shutting down harmful genes, for example by disrupting a faulty protein or blocking a viral receptor. Yet many diseases arise not because a gene is overactive, but because a beneficial gene is silenced when the body needs it most. In those cases, the ability to reactivate a gene, rather than destroy it, could restore a missing function without permanently altering the genome.

Epigenetic silencing is central to this problem, since chemical tags can keep a gene quiet even when its DNA sequence is perfectly intact. By targeting those tags, the new CRISPR approach can revive genes that were switched off by the cell’s own regulatory machinery, offering a way to correct disease states that stem from suppressed gene expression. The work shows that removing these marks can reawaken genes that had been effectively locked away, a strategy that directly addresses the question of new possibilities for treating conditions where turning genes back on is the key therapeutic move.

How the new CRISPR activator actually works

At the heart of the method is a familiar component: a CRISPR guide that steers a protein complex to a chosen DNA sequence. Instead of the classic nuclease that cuts DNA, researchers fuse this guide to enzymes that can remove methyl groups or other chemical marks from DNA and histones. When the complex arrives at a silenced gene, it does not break the strand, it chemically edits the local environment so that the gene becomes accessible again to the cell’s transcription machinery.

This design turns CRISPR into a programmable epigenetic editor, capable of dialing gene activity up without changing the letters of the genetic code. Earlier work had already shown that CRISPR could be repurposed as a light switch for genes, with one group describing a tool that flips genes on and off like a switch by attaching regulatory domains to a catalytically inactive CRISPR protein. That earlier system, reported in Apr and described as a way to turn the light switch back on, paved the way for the current strategy, which goes a step further by erasing the very marks that kept the gene dark.

Safer therapies for inherited disorders

The most immediate excitement around this non-cutting CRISPR approach centers on inherited diseases, where a single misregulated gene can have lifelong consequences. In sickle cell disease, for example, the problem is a mutation in the adult hemoglobin gene, but one promising strategy is to reactivate fetal hemoglobin, which the body naturally silences after birth. A tool that can precisely remove the epigenetic tags that keep fetal hemoglobin off could restore healthy red blood cell function without touching the mutated gene at all.

Researchers behind the new work explicitly frame their method as a way to unlock safer treatments for inherited disorders, since it avoids the double-strand breaks that have raised safety questions in some gene therapy trials. By focusing on epigenetic control, they aim to correct disease phenotypes by restoring normal gene expression patterns, rather than rewriting DNA. One report on this line of research notes that such a new CRISPR technique could unlock safer treatments for inherited disorders by targeting silenced or suppressed genes instead of permanently altering the genome.

CRISPR’s evolution from bacterial defense to precision switch

To understand how radical this shift is, it helps to remember where CRISPR started. The system was first recognized in bacteria as “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats,” a kind of genetic mugshot gallery that helps microbes recognize and cut viral DNA. When scientists adapted CRISPR for human cells, they leaned heavily on that cutting function, using it to snip out unwanted sequences or introduce new ones at specific sites.

Over the past decade, however, CRISPR has steadily evolved from a blunt cutter into a modular platform. Variants that lack cutting activity have been fused to activators, repressors, and base editors, turning the original bacterial defense into a Swiss Army knife for gene control. A brief history of CRISPR traces this trajectory from Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats in microbes to sophisticated tools that can silence or activate genes without touching the underlying sequence, setting the stage for the latest epigenetic activators.

On-off switches and reversible control

One of the most important conceptual advances has been the idea that gene editing should be reversible. Instead of permanently shutting down a gene, researchers have sought ways to turn it off for a while, then restore its activity if needed. Earlier work introduced a system sometimes called CRISPRoff, which uses targeted epigenetic modifications to silence genes while leaving the DNA intact, and a complementary CRISPRon to bring them back.

That reversible approach showed that gene expression could be controlled like a dimmer, with the underlying code untouched. In Apr, a team described a new CRISPR method as an on-off switch for gene editing, emphasizing that it could control gene expression while leaving the underlying DNA sequence unchanged, even at regions that do not code for proteins. The latest non-cutting activator builds directly on that logic, focusing on flipping genes back on in a controlled way rather than relying on permanent edits.

What makes the new activation strategy different

What sets the newest technique apart is its focus on removing, rather than adding, epigenetic marks at specific genes. Earlier CRISPR-based activators often worked by recruiting transcriptional machinery or adding activating marks, which could be powerful but sometimes transient. By stripping away the silencing tags that the cell had placed on a gene, the new method aims to restore a more natural pattern of activity, closer to what the gene would show if it had never been shut down.

This distinction matters for long term control. If the cell’s own regulatory systems see a gene as “normal” again once the silencing marks are gone, the hope is that expression will persist without constant intervention. The recent report on this work describes how a new CRISPR breakthrough can remove chemical tags that had kept genes off, allowing them to stay active without repeated editing. That approach could reduce the need for ongoing treatment and lower the risk of off target effects from repeated CRISPR exposure.

Implications for sickle cell disease and beyond

The clearest near term application is in blood disorders, where cells can be edited outside the body and then returned to the patient. In sickle cell disease, reactivating fetal hemoglobin has already shown clinical promise, and a non cutting CRISPR activator could make that strategy safer by avoiding double strand breaks in hematopoietic stem cells. The team behind the new work explicitly frames their approach as opening “New Possibilities for Treating Sickle Cell Disease,” highlighting how epigenetic reactivation could complement or even replace current editing strategies that disrupt regulatory genes.

Beyond sickle cell, the same logic could apply to other conditions where beneficial genes are epigenetically silenced, from some forms of thalassemia to certain metabolic and neurological disorders. By focusing on the chemical marks that keep these genes quiet, rather than the DNA itself, clinicians could design therapies that are both more targeted and more reversible. The report that discusses New Possibilities for Treating Sickle Cell Disease frames this as a way to give patients new options without the same level of genomic risk that comes with cutting based edits.

The road ahead for non-cutting gene control

For all its promise, the new CRISPR activation strategy still faces practical hurdles before it can move into routine clinical use. Delivering the editing machinery to the right cells in the body, ensuring that epigenetic changes are specific and durable, and monitoring for unintended effects on other genes will all require careful testing. Regulators will also need to decide how to classify therapies that change gene activity without altering DNA sequence, a gray area between traditional drugs and permanent gene edits.

Yet the direction of travel is clear. CRISPR is steadily shifting from a tool that breaks DNA to one that rewires gene regulation with increasing finesse, using the same targeting logic but gentler molecular payloads. As techniques that remove or add epigenetic marks mature, I expect the field to talk less about “editing genes” and more about “editing gene states,” a conceptual shift already visible in work that treats CRISPR as an on-off switch for gene expression. The latest breakthrough that flips genes on without cutting DNA is a decisive step in that evolution, and it will shape how scientists, clinicians, and patients think about the risks and rewards of rewriting biology.

More from Morning Overview