NASA is backing a new generation of nuclear rockets that could compress the months-long journey to Mars into a sprint measured in weeks. The most ambitious concepts on the table promise crewed trips in as little as 45 days, a shift that would rewrite the medical, engineering, and political calculus of human exploration of the Red Planet. I see this as less a single breakthrough than a convergence of propulsion physics, advanced reactor fuels, and a renewed appetite for risk in deep space.

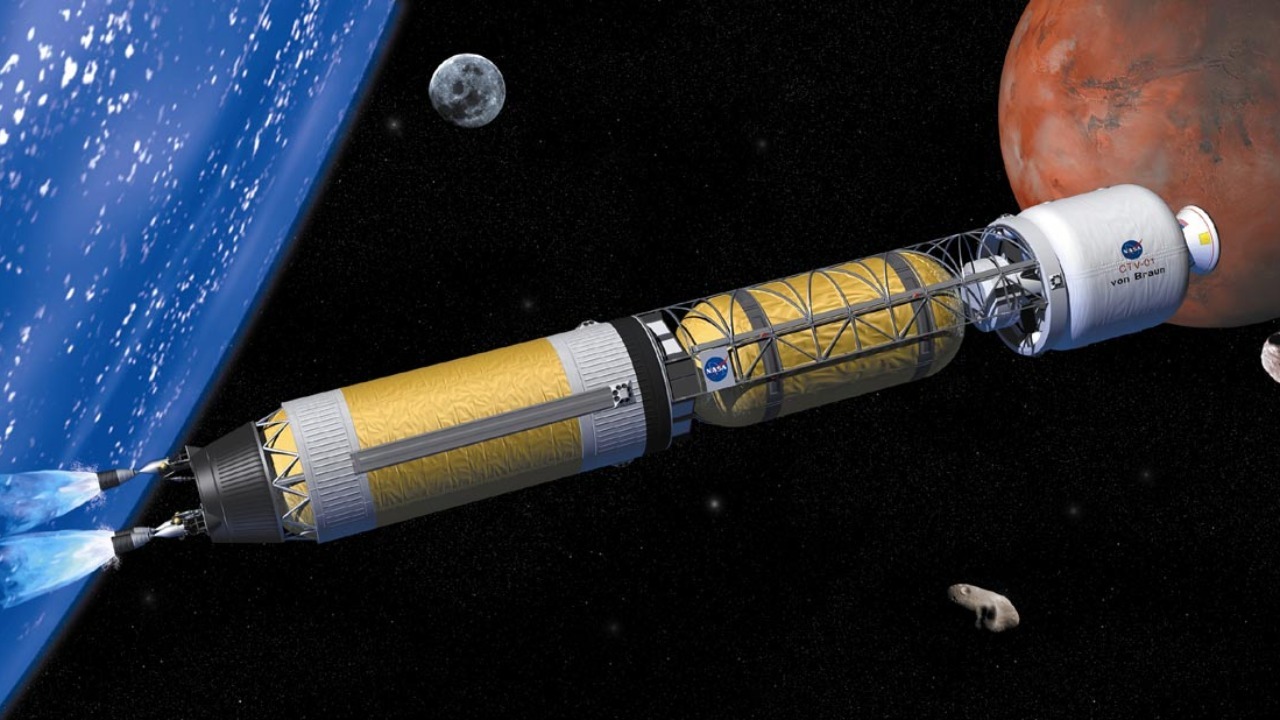

Behind the headline is a quiet revolution in how engineers think about getting beyond the Moon. Instead of squeezing marginal gains out of chemical engines, NASA and its partners are turning to Nuclear systems that can deliver far higher efficiency and sustained power, both for thrust and for onboard electricity. If these designs move from paper to flight hardware, the familiar image of a slow, vulnerable cruise to Mars could give way to something closer to an interplanetary express.

Why cutting the Mars trip to 45 days matters

The promise of reaching Mars in 45 days is not just a speed record, it is a direct response to the brutal realities of long-duration spaceflight. Traditional chemical missions can keep astronauts in deep space for up to three years, with months spent coasting between planets, which multiplies exposure to radiation, microgravity bone loss, and psychological strain. By shrinking the transit window, mission planners can slash the time crews spend outside Earth’s protective magnetic field and reduce the amount of food, water, and spare parts that must be launched from the ground.

NASA’s own internal studies of a nuclear propulsion concept highlight that shorter travel times are vital for both science and human space exploration, since faster trips mean less radiation dose and more flexible mission profiles that can respond to launch windows and planetary alignment. In that work, engineers describe a nuclear-powered system that could send a crewed vehicle to Mars in as little as 45 days, a figure that has quickly become a benchmark for what next-generation propulsion should aim to achieve. I see that number less as a hard requirement and more as a signal that the agency is no longer satisfied with incremental improvements on chemical rockets.

From chemical rockets to Nuclear propulsion

For more than half a century, Mars mission architectures have been Based on chemical propulsion, the same basic technology that powered Apollo and today’s commercial launchers. In that regime, a crewed Mars mission can stretch to three years when surface operations and return transit are included, largely because chemical engines burn propellant quickly and then coast, leaving spacecraft to drift along energy-efficient but slow trajectories. The physics of specific impulse, essentially how much thrust you get per unit of propellant, has boxed chemical systems into a corner where meaningful gains are hard to find.

Nuclear propulsion breaks that pattern by using a compact reactor to heat propellant or generate electricity continuously, which allows higher exhaust velocities and more efficient use of mass. As part of a broader push to modernize deep space transport, NASA has examined nuclear thermal and nuclear electric options that could dramatically cut trip times to Mars compared with conventional rockets. Reporting on a new NASA nuclear rocket plan notes that, compared with missions Based on chemical propulsion that might last up to three years, a nuclear system could enable much shorter journeys to Mars, which is why the agency is investing in designs that can be thoroughly tested and validated before any crew flies. In my view, this is a classic trade of complexity for performance, one that space programs have made repeatedly when the scientific payoff is high enough.

The bimodal “wave rotor” rocket that changed the conversation

The most eye-catching of the new concepts is a bimodal nuclear propulsion system that uses a so-called wave rotor topping cycle to squeeze more performance out of its reactor. In a bimodal design, the same nuclear core can operate in a high-thrust mode for rapid acceleration and a high-efficiency mode for cruising or power generation, which gives mission planners a flexible tool for both fast transits and robust in-space power. The wave rotor element adds a pressure-boosting stage that effectively supercharges the propellant flow, raising exhaust velocity without proportionally increasing reactor size.

Analyses of this new class of bimodal nuclear propulsion system describe how the wave rotor topping cycle could enable a spacecraft to reach Mars in roughly a month and a half, while also providing electrical power for onboard systems and scientific instruments. One detailed study explains that this bimodal design enables fast transit for manned missions, explicitly citing 45 days to Mars, and argues that such a system could revolutionize deep space exploration. A separate technical overview calls it a new class of bimodal nuclear propulsion that uses a wave rotor topping cycle and traces its lineage back to nuclear work by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) that launched in 1955, underscoring how long these ideas have been percolating before modern materials and computing made them practical enough to revisit in earnest, as described in The race to space. I see this as a bridge between mid‑20th‑century nuclear ambitions and today’s more disciplined engineering culture.

Inside the Nuclear space engine backed by NASA

Alongside the academic designs, a commercial effort is taking shape around a Nuclear space engine backed by NASA that aims to turn these principles into hardware. The concept pairs a compact nuclear reactor with an electric propulsion system, using the reactor to generate high levels of electrical power that can drive advanced ion or Hall-effect thrusters. This hybrid approach trades raw thrust for extraordinary efficiency, allowing a spacecraft to accelerate gently but continuously over long periods, which is exactly what is needed to hit ambitious transit times without hauling enormous propellant tanks.

Reporting on this project explains that the Nuclear space engine backed by NASA could fly humans to Mars in just 45 days by using a nuclear reactor to power an electric propulsion system rather than relying solely on chemical thrust. The same coverage identifies the industrial partner as Space Nuclear Power Corporation, also known as Space Nuclear Power Corporation in a separate reference, which is working to commercialize the core technologies behind this engine, as noted in a follow‑on description of the Space Nuclear Power Corporation effort. From my perspective, this public‑private model mirrors what has already transformed low Earth orbit, with NASA setting performance targets and industry racing to meet them.

The breakthrough fuel that can survive 4,220°F

Even the most elegant propulsion cycle is useless if the reactor fuel cannot survive the brutal conditions inside a nuclear rocket, which is why materials science has become a central part of the Mars sprint story. Traditional reactor fuels were never designed to be blasted with propellant at extreme temperatures while maintaining structural integrity and predictable behavior. To make a 45‑day Mars trip feasible, engineers need fuel that can run hot enough to deliver high exhaust velocities without melting, cracking, or shedding particles into the flow.

A recent development in this area comes from General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems, which has unveiled New nuclear fuel that can withstand 4,220°F heat while powering rockets to Mars in just 45 days. The company, identified as General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems, argues that this fuel could change the trajectory of human space exploration by enabling much higher performance compared with conventional rocket systems, particularly when paired with advanced reactor designs. Another report, titled This Nuclear Propulsion Reactor Fuel Could Take Humans To Mars In, describes how this fuel can operate at peak performance for extended periods and explicitly frames it as the key to getting humans to Mars in 45 Days, crediting the work to By Joshua Hawkins Jan and noting that the discussion took place in the evening EST. I see this as a reminder that the path to Mars runs as much through advanced ceramics and composites as it does through grand mission architectures.

NASA, DARPA, and the rise and fall of DRACO

For all the excitement around new fuels and engines, the institutional story is more complicated, particularly when military agencies are involved. NASA has not been working alone on nuclear propulsion; it teamed up with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to pursue a demonstrator known as DRACO, short for Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations. The idea was to flight test a nuclear thermal rocket in space, proving that a compact reactor could safely operate in orbit and provide the kind of thrust needed for rapid maneuvers between Earth and the Moon, with an eye toward future Mars missions.

Coverage of the partnership notes that NASA and DARPA planned to test a nuclear-powered rocket that could take humans to Mars in record time, with NASA aiming to test a nuclear thermal propulsion system in space after earlier ground-based work that first tested such engines in the 60s, as described in a report on NASA and DARPA. However, the DRACO program ran into headwinds, particularly around launch safety and regulatory approvals for putting a nuclear reactor into orbit. One analysis of nuclear-powered rockets points out that Safety Concerns Put DRACO Plans on a Potentially Long Hold The initial goal for the DRACO program was to conduct a test flight, but officials later described the path forward as not impossible but rather difficult, capturing the political and technical friction that often accompanies nuclear projects, as detailed in Safety Concerns Put DRACO Plans. Ultimately, The US Department of Defense, through the DOD and its Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, decided to cancel DRACO, with DARPA confirming that the project was ended rather than proceed with launching a nuclear reactor into orbit, as reported in a notice that DRACO project cancelled. I read this as a sign that while the physics of nuclear rockets are compelling, the governance and public acceptance questions remain unresolved.

Health, safety, and political risk in nuclear deep space

Any plan to send a nuclear reactor into space, let alone one powerful enough to drive a crewed Mars ship, must grapple with a layered set of risks. On the health side, the central argument for faster transit is that it reduces the time astronauts spend bathing in cosmic rays and solar particles, which can damage DNA and increase cancer risk. Yet nuclear propulsion introduces its own safety questions, from how to contain radioactive material in the event of a launch failure to how to manage reactor shutdown and disposal at the end of a mission.

Regulators and defense officials have already signaled how sensitive these issues are through their handling of DRACO, where concerns about launching a nuclear reactor into orbit contributed to the program’s pause and eventual cancellation. The same dynamics will shape any NASA-led Mars vehicle, even if it uses different reactor designs or orbits. In my view, the political risk is twofold: there is the immediate fear of a launch accident that could spread contamination, and the longer-term worry that normalizing nuclear hardware in space might blur lines between civilian exploration and military deployment. Navigating that landscape will require not just engineering rigor but also transparent communication with the public and international partners.

What a 45-day Mars mission would actually look like

Stripping away the hype, a 45‑day Mars mission would still be a complex, high‑stakes operation that pushes every part of the spaceflight stack. The trajectory would likely involve a high‑energy departure from Earth orbit, a sustained period of powered flight using either nuclear thermal or nuclear electric propulsion, and a carefully timed braking phase to match Mars’ orbit, all while managing life support, radiation shielding, and onboard maintenance. Unlike traditional Hohmann transfer orbits, which trade time for fuel efficiency, this kind of sprint profile would burn more propellant and demand more from the propulsion system, but it would keep the crew’s deep space exposure to a fraction of current plans.

Inside the spacecraft, the shorter trip would change daily life in subtle but important ways. With less time in microgravity, crews might experience fewer musculoskeletal issues, and mission planners could pack lighter on consumables, freeing mass for better shielding or scientific payloads. At the same time, the intensity of operations would increase, since navigation, engine management, and contingency planning would all be compressed into a tighter window with less margin for error. I see this as a shift from endurance expedition to high‑tempo campaign, one that will demand new training regimes and perhaps new roles on board, such as dedicated reactor operators or propulsion specialists alongside pilots and scientists.

The road ahead for NASA’s nuclear rocket ambitions

With DRACO shelved and several competing concepts in play, NASA’s path to a nuclear Mars vehicle is neither linear nor guaranteed. The agency must decide how to balance nuclear thermal and nuclear electric approaches, how much to lean on partners like Space Nuclear Power Corporation and General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems, and how to phase ground tests, in‑space demos, and eventual crewed missions. Funding cycles and shifting political priorities will shape those choices, as will the pace of progress in related areas like radiation shielding, autonomous navigation, and in‑situ resource utilization on Mars.

Yet the underlying motivation remains clear: chemical rockets alone are unlikely to deliver the kind of sustainable, repeatable Mars access that policymakers and scientists increasingly expect. By pursuing nuclear propulsion, NASA is betting that higher performance at the engine level can unlock entirely new mission architectures, from rapid cargo runs to agile crew rotations that treat Mars less as a one‑off destination and more as a reachable neighbor. As I weigh the technical reports against the institutional turbulence, I come away convinced that some form of nuclear rocket will eventually fly under NASA’s banner, even if the first missions fall short of the headline‑grabbing 45‑day mark. The question is not whether the physics works, but whether the politics, safety frameworks, and industrial base can align in time to make the next great leap before another generation passes.

More from MorningOverview