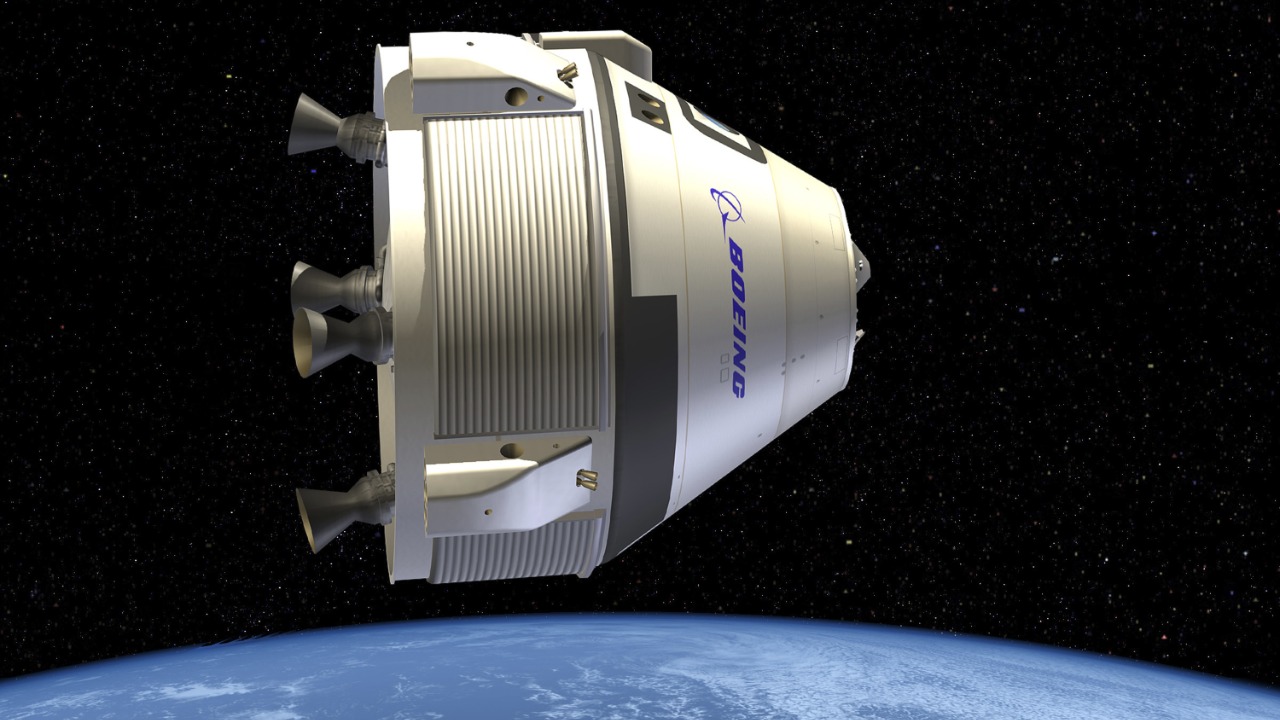

NASA has quietly but decisively scaled back its ambitions for Boeing’s Starliner capsule, cutting a multibillion‑dollar crew transport deal to just four operational flights after a troubled astronaut mission. The move keeps Starliner in the game as a backup to SpaceX, but it also signals a sharp reset of expectations for a program that was once supposed to share the load of routine trips to the International Space Station.

By trimming the contract and reshaping the final missions, NASA is trying to balance redundancy, safety and cost at a moment when Boeing is under intense pressure across its commercial and defense businesses. I see this as less a sudden loss of faith than a pragmatic admission that the agency no longer needs, or can justify, the six full‑fledged crewed flights it originally bought.

The contract cut: from six crewed flights to four

The core change is straightforward: NASA and Boeing have agreed to reduce the number of planned Starliner missions under the Commercial Crew program from six to four, effectively shrinking a roughly $4.5 billion services deal to match a narrower role. The revised arrangement follows a botched astronaut flight that exposed technical and operational weaknesses, prompting NASA to reassess how many times it really needs to put Starliner into service for human transport.

According to reporting on the updated agreement, the agency and the company decided around Nov 23, 2025 that the original six‑mission plan no longer made sense after the problematic crewed test, and that four flights would be sufficient to meet NASA’s remaining station needs while still honoring the bulk of Boeing’s Commercial Crew obligations.

Why NASA pulled back after a botched mission

NASA’s decision is rooted in performance, not just budget arithmetic. The agency had already absorbed schedule slips and technical fixes on Starliner, but the botched astronaut mission forced a deeper look at whether the capsule could reliably shoulder a long series of crew rotations. When a crewed test exposes enough issues to trigger a wholesale contract revision, it is a clear sign that confidence has been dented, even if the program is not being canceled outright.

Reporting on the change notes that NASA reduced Starliner flights from six to four after that flawed astronaut outing, with the reassessment crystallizing around Nov 23, 2025, when officials concluded that the capsule’s role should be scaled back rather than expanded.

Optional missions and a pivot toward cargo

Instead of simply canceling flights, NASA has tried to keep some flexibility by making the last two missions in the revised plan optional. That structure gives the agency room to call on Starliner if circumstances change, for example if another vehicle is grounded or if station operations demand extra capacity, without locking in a full slate of crewed trips that it may never need to fly.

At the same time, NASA and Boeing are steering Starliner toward a different kind of work, with the next mission expected to be an uncrewed cargo test rather than a passenger flight. Coverage of the updated manifest describes how the number of astronaut trips has been cut to four and how the next scheduled outing is a cargo mission targeted for April 2026, a shift that reflects both operational caution and a desire to extract value from the hardware in a lower‑risk role, as detailed in Latest News Today coverage of the change.

What the trimmed deal means for Boeing

For Boeing, the contract cut is both a financial and reputational setback. The Commercial Crew deal was supposed to be a showcase for the company’s human spaceflight capabilities, a counterweight to its troubles in commercial aviation and a steady revenue stream tied to repeat ISS rotations. Reducing the manifest to four flights, with the final two treated as optional, narrows that runway and underscores how hard it has been for Boeing Starliner to match the reliability and cadence of its main rival.

The revised agreement, reported around Nov 23, 2025, makes clear that the last two missions are no longer guaranteed, which means Boeing must now treat them as opportunities to be earned rather than entitlements baked into the original $4.5 billion framework.

NASA’s redundancy strategy in the SpaceX era

From NASA’s perspective, trimming Starliner’s role is less risky than it would have been a decade ago, because SpaceX has already proven it can handle a steady rhythm of crewed flights to the station. The agency still values redundancy, but it no longer needs two providers flying at equal tempo to keep the ISS staffed, especially as the station nears the later years of its planned life and the economics of each additional mission are scrutinized more closely.

By keeping four Starliner flights on the books, with two more in reserve as optional, NASA preserves a backup capability without overcommitting to a vehicle that has struggled to meet its original schedule and performance targets. In practice, that means SpaceX will likely remain the primary workhorse for astronaut transport, while Boeing’s capsule shifts into a supporting role that can be dialed up or down depending on how future tests and cargo runs perform.

The broader signal for commercial crew and future stations

I see the Starliner cutback as an early test of how NASA will manage commercial partnerships in the coming era of private space stations and multiple crew vehicles. The agency is signaling that contracts are not static trophies but living documents that can be reshaped when performance, cost or strategic needs change. That is a message not just for Boeing, but for every company hoping to sell crew or cargo services to low Earth orbit in the 2030s.

At the same time, NASA is stopping well short of walking away from Boeing. By preserving four flights, planning a cargo test and leaving the door open to optional missions, it is giving the company a chance to prove that Starliner can be a reliable, if more limited, part of the human spaceflight ecosystem. How those flights unfold will help determine whether Boeing remains a central player in crew transport or becomes a niche provider in a market that is rapidly tilting toward newer vehicles and privately operated stations.

More from MorningOverview