NASA is quietly rewriting the script for human exploration of the Red Planet, turning robots from remote-controlled tools into autonomous partners tasked with keeping crews alive far from home. Instead of waiting for astronauts to solve every problem in real time, the agency is training machines to scout hazards, build infrastructure and even repair life support systems before a single human boot presses into Martian dust. The stakes are blunt: if these robots fail, the first people on Mars may not get a second chance.

As I look across the latest mission plans and technology demos, a clear pattern emerges. NASA is designing a Mars campaign in which robotic systems handle the most dangerous and repetitive work, while humans focus on decisions, science and improvisation. That shift is reshaping everything from spacecraft architecture to how engineers think about risk, and it is pulling in a wider ecosystem of humanoid prototypes, commercial robots and off-world construction experiments that all point toward the same goal: survival on a hostile world.

Why survival on Mars starts with robots, not astronauts

The basic physics of interplanetary travel make it obvious why machines have to go first. When astronauts finally head for Mars and back, NASA expects their vehicle to return with more than a billion miles on the odometer, a journey so long that every kilogram of cargo and every watt of power must be justified. In that context, sending robots ahead to assemble habitats, test resources and map safe landing zones is not a luxury, it is the only rational way to reduce the risk that a crew arrives to find an unlivable environment.

NASA’s own planning for Getting There and Back to Mars and home again leans heavily on this logic, describing how early missions will rely on robotic scouts to understand the terrain and weather on the Red Planet before people commit to landing. I see that as a quiet admission that human senses and reflexes are not enough when signals take minutes to cross space and dust storms can swallow solar arrays without warning. The only way to stack the odds in favor of survival is to surround astronauts with machines that have already learned the landscape and can keep learning while they sleep.

Inside NASA’s new generation of robotic “caretakers”

Behind the scenes, NASA is already training a new class of robotic caretakers that are meant to operate as the first residents of Mars. Reporting on how NASA Is Training Robots to Keep Humans Alive on Mars describes systems that ingest data from multiple Mars missions, then use that knowledge to practice tasks like navigation, sample handling and infrastructure inspection in simulated environments. In effect, the agency is building up a library of Martian experience for robots long before any human can accumulate that kind of intuition.

What stands out to me is how explicit the survival framing has become. These machines are not just there to collect pretty panoramas, they are being prepared to monitor power systems, track environmental changes and respond to anomalies that could threaten a future habitat. By training algorithms on years of orbital and surface data from Mars, NASA is trying to give its robotic caretakers the pattern recognition they will need to spot trouble early, whether that is a dust buildup on radiators or a subtle shift in local weather that could precede a storm.

From Perseverance to pre-crew pathfinders

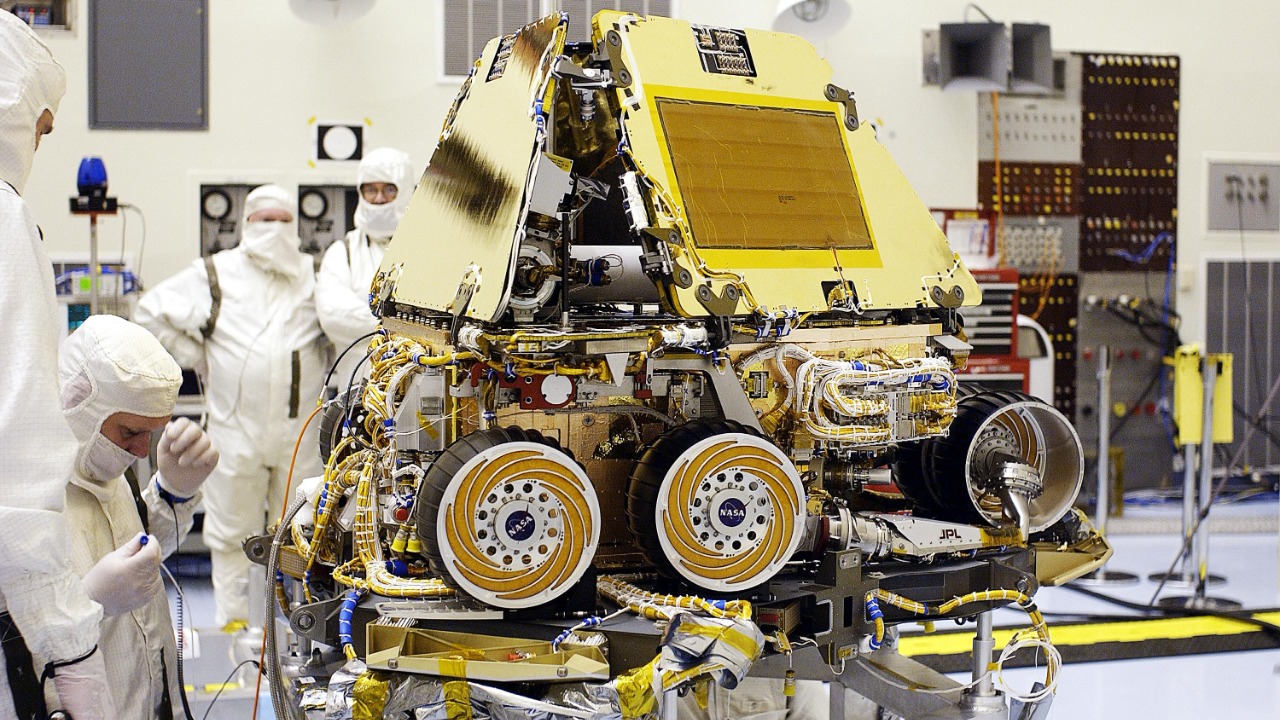

The shift toward robotic guardianship builds on a long lineage of Mars explorers, and the Perseverance rover is a clear bridge between pure science missions and future support roles. In a NASA presentation about NASA’s New Mars Robot Rover, Perseverance, engineers walk through how the rover’s autonomous navigation, sample caching and environmental sensing push far beyond earlier platforms. I see Perseverance as a prototype for the kind of semi-independent decision making that pre-crew robots will need when they are asked to manage infrastructure instead of just instruments.

Perseverance’s ability to pick its own driving routes, avoid hazards and coordinate complex sequences without minute-by-minute human input is exactly the behavior that will be required when robots are tasked with preparing landing pads or inspecting fuel depots. The rover’s work in Jezero Crater shows that a machine can interpret terrain, execute multi-step plans and recover from minor errors on its own, all of which are essential if future pathfinders are to operate safely in the long communication gaps that separate Mars from Earth.

Learning to build on Mars, one tower at a time

Keeping humans alive on Mars will depend on more than rovers, it will require robots that can assemble and maintain large structures in low gravity and abrasive dust. That is why I pay close attention to demonstrations like the one in which GITAI autonomous robots assembled a 5 meter communication tower for off-world habitats. Even though that test took place closer to home, it directly tackles the problem of how to build tall, stable infrastructure with limited human oversight, a core challenge for any Martian settlement.

The fact that a GITAI system can coordinate multiple limbs, handle structural components and complete a tower build with minimal intervention suggests a path forward for constructing solar farms, antenna arrays and even pressure shells on Mars. I see these experiments as rehearsal for the day when a cargo lander touches down on the Red Planet, opens its doors and a team of robots begins bolting together the hardware that will later keep air, water and data flowing for human crews.

Humanoid helpers: from “sort of” man to Valkyrie

Not all of the robots being groomed for Mars look like industrial arms or six-wheeled rovers. Some are deliberately humanoid, designed to operate tools and interfaces built for people, and to step into tasks that would otherwise expose astronauts to lethal risk. A detailed look at how future missions may be assisted by humanoid robots describes One Small Step For a Sort of Man, a concept in which a robot walks into danger in place of a human. By the time a human is finally ready to set foot on Mars, that reporting suggests he or she could have a team of such assistants handling the most punishing chores.

NASA’s own flagship in this category is Valkyrie, described as Nasa’s Humanoid Robot Leading The Way To The Moon and Mars. I see Valkyrie as a testbed for everything from habitat maintenance to emergency response, a machine that can climb ladders, manipulate valves and operate in spacesuits’ shadow where humans might be too fragile or too slow. If a solar array needs to be cleared during a dust storm or a leak must be patched on the exterior of a habitat, sending a humanoid robot instead of a person could be the difference between a close call and a fatal accident.

Commercial robots and the Starship factor

The push to train robots as guardians of human life on Mars is not limited to NASA. Commercial players are weaving their own machines into interplanetary plans, and that convergence could accelerate the pace of development. A close look at SpaceX’s Mars architecture notes that, for the inaugural launches of Starship to Mars, the spacecraft will carry Optimus robots, like those shown in an illustration tied to Musk’s electric car company, Tesla. In other words, SpaceX is planning to send its own general purpose humanoids ahead of or alongside cargo, echoing NASA’s instinct to let machines take the first risks.

I read that as a sign that the Mars ecosystem will likely be a blend of government and private robotics, each tuned to different tasks but all contributing to the same survival puzzle. Optimus units could handle repetitive logistics inside pressurized spaces, while NASA’s specialized systems focus on scientific and critical infrastructure work outside. The more diverse the robotic workforce, the more resilient a future settlement becomes, because no single failure mode can take down every system at once.

From the Moon to Mars: a robotics testbed in deep space

NASA is not waiting for Mars to start this robotic apprenticeship. The agency is already using lunar missions as a proving ground for the technologies that will later protect crews on the Red Planet. In its own words, NASA is developing key technologies to send astronauts to Mars as early as the 2030s, and robotics sits at the center of that effort. I see the Moon as a nearby sandbox where engineers can test autonomy, teleoperation and maintenance routines with real dust, real vacuum and real time delays, but with the safety net of relative proximity to Earth.

Every time a robot assembles a structure on the lunar surface or services a piece of hardware in orbit, NASA learns something about how to design systems that will not fail catastrophically after years of exposure to radiation and thermal cycling. Those lessons will feed directly into the machines that are now being trained on Martian data, tightening the feedback loop between simulation and reality. By the time a crewed Mars mission is ready, the robots that greet them should already have survived a gauntlet of lunar trials that prove they can handle the harshest conditions.

The human-robot partnership that will decide who survives

All of this technology adds up to a simple but profound shift in how I think about exploration. The first humans on Mars will not be heroic loners planting flags on an untouched world, they will be the latest arrivals in a community already populated by rovers, towers, humanoids and autonomous systems that have been working for years to make the place survivable. Their job will be to collaborate with those machines, to interpret their data, override their mistakes and push them into new roles as circumstances change.

If NASA, Nasa’s partners and commercial players like the teams behind Optimus and GITAI get this right, the phrase “keeping humans alive on Mars” will describe a shared responsibility between flesh and code. The robots will handle the relentless, unforgiving tasks that do not care about fatigue or fear, while people bring creativity, judgment and a sense of purpose that no algorithm can match. Survival on the Red Planet will not be a triumph of one over the other, but a test of how well we can train our machines to be the kind of colleagues we will trust with our lives, a trust that is already being built today in labs, test ranges and simulated Martian landscapes from Jan to Dec, from the first NASA training runs to the long term vision of humans to Mars and back.

More from MorningOverview