NASA’s confirmation that comet 3I/ATLAS is experiencing a subtle but real non‑gravitational acceleration has turned a niche orbital puzzle into a broader test of how we interpret strange visitors from beyond the solar system. The object’s behavior is now feeding a widening scientific and cultural rift over whether to treat such anomalies as exotic but natural physics or as possible hints of technology.

I see the 3I/ATLAS debate as a stress test for modern astronomy, forcing researchers to weigh conservative models of comet activity against bolder ideas about interstellar debris and even engineered artifacts, all while the comet races through the inner solar system and public attention intensifies.

What NASA has actually confirmed about 3I/ATLAS

The first step in cutting through the noise is to be precise about what NASA has and has not said. The agency’s technical material describes 3I/ATLAS as an interstellar comet whose trajectory cannot be explained by gravity alone, with its orbit showing a small but measurable deviation that qualifies as non‑gravitational acceleration. In practical terms, that means the comet is either speeding up or changing course slightly compared with what a purely gravitational path would predict, a pattern that NASA details in its dedicated facts and FAQs.

NASA’s broader overview of the object places 3I/ATLAS in the same rare category as earlier interstellar visitors, emphasizing that it arrived from outside the solar system and is now on a one‑way outbound trajectory that will never return. That context matters, because it means astronomers cannot wait for a second pass to refine their models, they have a narrow window to track the comet’s brightness, outgassing, and motion before it fades into deep space, a point underscored in the agency’s main 3I/ATLAS overview.

How the non‑gravitational acceleration was detected

The claim that 3I/ATLAS is accelerating in a non‑gravitational way rests on painstaking orbit fitting rather than a single dramatic measurement. Astronomers compare repeated position observations against a purely gravitational trajectory, then look for systematic residuals that point to an extra push, and in this case the data show a consistent offset that grows over time. Reporting on the analysis explains that the effect is small in absolute terms but statistically significant, enough that researchers are confident it is not just noise in the tracking of the comet’s path, a conclusion summarized in coverage of the object’s measured acceleration.

What makes this detection especially contentious is that it echoes the earlier saga of 1I/‘Oumuamua, where a similar non‑gravitational term sparked years of debate. For 3I/ATLAS, modelers have again introduced additional forces into their equations, then tested whether those terms improve the fit to the observed positions, and the latest work argues that a specific pattern of outgassing can reproduce the anomaly. That interpretation, which frames the acceleration as a natural by‑product of volatile material venting from the surface, is laid out in detail in a recent study of the non‑gravitational acceleration.

The natural explanation: jets, outgassing, and interstellar ice

On the conservative side of the debate, planetary scientists argue that 3I/ATLAS behaves like a comet that happens to come from another star, not like a piece of hardware. In that view, the extra acceleration is simply the recoil from jets of gas and dust erupting from the surface as sunlight heats volatile ices, a process that has been observed in many solar system comets and is now being applied to this interstellar case. The recent modeling work treats 3I/ATLAS as an unfamiliar but still natural iceberg, with its composition and spin state tuned so that asymmetric outgassing produces the measured deviation from a purely gravitational orbit, a scenario described in the study that seeks to explain the acceleration.

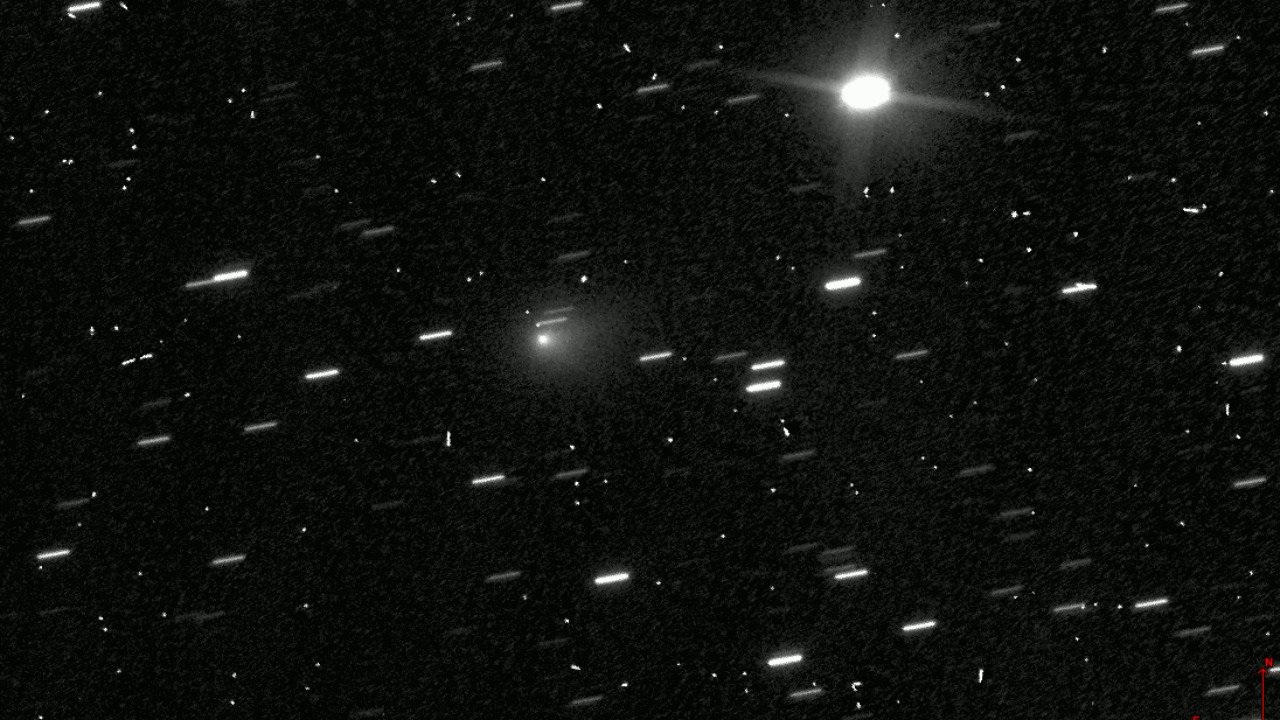

Fresh imagery has strengthened that argument by revealing active features on the comet itself. High‑resolution telescope observations show a distinct jet of material blasting away from 3I/ATLAS and pointing roughly toward the Sun, a visual confirmation that the object is venting gas in a focused way rather than just shedding material evenly in all directions. That kind of directed plume is exactly the sort of natural engine that can nudge a comet off its gravitational track, and it is highlighted in new images that capture the comet as it blasts a jet into space.

The provocative alternative: could 3I/ATLAS be engineered?

Not everyone is satisfied with the natural outgassing story, and 3I/ATLAS has quickly become a fresh test case for more speculative ideas about interstellar objects. Some researchers argue that when an object from another star shows both an unusual shape and a non‑gravitational acceleration, it is at least worth asking whether we are seeing a piece of alien technology rather than a random shard of ice. That line of reasoning has been applied to 3I/ATLAS in a detailed essay that weighs whether its anomalies might flag an engineered artifact or, alternatively, an exotic but still natural iceberg, a tension explored in an analysis of whether the comet’s behavior could signal alien technology.

I find that framing useful less as a literal claim that 3I/ATLAS is a spacecraft and more as a way to stress‑test our assumptions. If every anomaly is automatically forced into a conventional comet model, the argument goes, astronomers risk missing genuinely new categories of objects, whether they are natural or artificial. At the same time, the burden of proof for any technological interpretation is extremely high, and so far the observational record for 3I/ATLAS, including its visible jet and comet‑like coma, fits comfortably within the range of known comet behavior, even if its interstellar origin and detailed composition remain open questions.

Public fascination and the deepening rift in interpretation

As with ‘Oumuamua, the scientific disagreement over 3I/ATLAS has spilled quickly into the public sphere, where the gap between cautious modeling and bold speculation can widen into a full‑blown rift. Video explainers and panel discussions have amplified both sides, with some presenters walking viewers through the orbital mechanics and outgassing physics, and others leaning into the possibility of artificial origins. One widely viewed breakdown of the object’s trajectory and acceleration has helped popularize the idea that 3I/ATLAS is a crucial test of how we interpret interstellar visitors, a theme that runs through a detailed video analysis of the comet.

That divergence is not just academic, it shapes how the public understands the scientific process itself. When one set of experts emphasizes jets and ices while another foregrounds engineered sails or probes, audiences can come away thinking the field is hopelessly divided, even when most researchers cluster around the natural explanation. A separate discussion featuring astronomers and commentators has underscored how quickly the conversation can shift from data to narrative, with a popular round‑table video highlighting both the excitement and the frustration that come with trying to communicate subtle orbital anomalies to a broad audience hungry for definitive answers.

What 3I/ATLAS means for Earth and future observations

For all the drama around its acceleration, 3I/ATLAS is not a threat to Earth, and that distinction is important to keep clear. Current trajectory solutions show the comet passing through the inner solar system at a safe distance, with no credible impact scenarios in the models that incorporate both gravitational forces and the measured non‑gravitational term. Forecasts for its path and brightness suggest that the object will make a relatively close but harmless approach to the Sun and then head back out into interstellar space, a timeline that has been laid out in coverage of the comet’s expected pass by the Sun and Earth.

That safe trajectory gives astronomers a rare opportunity to study an interstellar comet in detail without the pressure of planetary defense concerns. Ground‑based observatories and space telescopes are already tracking how the jet structure evolves as 3I/ATLAS approaches and recedes from the Sun, and those observations will feed back into models of its composition and internal structure. The more precisely researchers can tie changes in brightness and morphology to shifts in the non‑gravitational acceleration, the better they can distinguish between competing explanations and refine the broader toolkit for interpreting future interstellar visitors.

Why this debate matters for the next interstellar visitor

In the end, the argument over 3I/ATLAS is less about this single comet and more about how the scientific community will handle the next wave of interstellar objects. Each new visitor arrives with limited observing time and incomplete data, and the frameworks built now will shape whether anomalies are treated as bugs in the models or as potential clues to something genuinely new. The current round of studies, from NASA’s orbital work to independent modeling of the acceleration, is already influencing how astronomers plan surveys and follow‑up campaigns for the next object that crosses the solar system’s boundary.

I see 3I/ATLAS as a kind of rehearsal, one that forces astronomers, communicators, and the public to confront how much uncertainty they are willing to live with when the data are intriguing but not definitive. If the natural outgassing explanation continues to hold up under scrutiny, it will strengthen confidence in using similar models for future anomalies, while still leaving room for outliers that refuse to fit. If, instead, new measurements reveal behavior that cannot be reconciled with jets and ices, the case for more radical interpretations will grow stronger, and the rift that has opened around this comet will become the starting point for an even more consequential debate.

More from MorningOverview