The return of two monumental stoneware vessels to the descendants of David Drake, a 19th century enslaved potter from South Carolina, marks a rare moment when a major museum has formally acknowledged Black family ownership of works created in bondage. The agreement, centered on pieces long held by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is being watched closely by curators, lawyers, and descendants who see it as a test case for how institutions confront the legacies of slavery embedded in their collections.

I see this as more than a single restitution story: it is a public reckoning with who has the right to claim authorship, value, and control over objects made under enslavement, and whether museums are prepared to share that power with the families whose histories those objects carry.

How an enslaved potter’s work ended up in a Boston museum

To understand why this transfer matters, it helps to start with David Drake himself, an enslaved man who lived in Edgefield, South Carolina, and produced thousands of large stoneware vessels in the decades before the Civil War. He is widely known today for signing his name and inscribing short poems on some of his jars, acts of authorship that defied laws and customs that sought to erase the literacy and individuality of enslaved people, and those signatures later helped scholars trace his surviving works into museum collections across the country, including Boston.

Reporting on the case notes that the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston acquired two of Drake’s monumental vessels, both made in Edgefield, through 20th century art market channels that did not involve his descendants, even though the jars were created while he was enslaved and working in potteries owned by white families who profited from his labor, a pattern that mirrors how many of his thousands of pots moved from plantation sites into private collections and eventually into institutions far from South Carolina after his death.

The unprecedented ownership agreement with Drake’s descendants

The recent agreement between the Museum of Fine Arts and Drake’s descendants breaks from that history by explicitly recognizing the family’s claim to the two vessels and transferring legal title to them. According to the museum’s own description of the deal, the descendants are now the official owners of the jars, while the institution retains them on long term loan so they can remain on public view, a structure that treats the family as rights holders rather than as symbolic stakeholders in a curatorial narrative about the artist.

Coverage of the negotiations underscores that this is not a routine deaccession but a carefully structured resolution that involved lawyers, provenance researchers, and descendant representatives who argued that works created under enslavement should be considered part of a family’s cultural inheritance, even when no bill of sale or direct chain of custody connects them to a specific heir, a position that pushes museums to rethink how they define ownership when the original maker was legally treated as property in the 19th century.

Why descendants say this case sets a precedent

For Drake’s descendants, the Boston agreement is not only about two jars but about establishing a model that other families can point to when they approach museums holding objects made by enslaved ancestors. In a detailed public statement shared within a community of museum professionals and advocates, supporters of the family described the resolution as a “very rare and likely precedent setting” example of a major institution recognizing descendant ownership of art created in bondage, language that reflects how unusual it is for museums to relinquish title in such cases and to frame it as a model.

I read that framing as a direct challenge to the long standing assumption that once an object enters a museum through purchase or donation, its legal status is settled forever; by asserting that the moral and historical claims of descendants can override that default, the Drake family and their allies are inviting other communities to ask whether quilts, carvings, tools, and other works made under slavery should be treated as part of Black family estates rather than as neutral artifacts of American history.

Inside the negotiations: law, ethics, and institutional change

The path to this agreement was not quick, and the reporting makes clear that it unfolded at the intersection of legal risk, ethical responsibility, and institutional self interest. Museum representatives acknowledged that they had to weigh their fiduciary duty to preserve the collection against the moral imperative to address the inequities baked into how those objects were acquired, a tension that played out in months of conversations with descendant leaders, outside advisors, and trustees who ultimately agreed that transferring title while retaining custody was a workable compromise for all parties.

Accounts of the talks also highlight how the museum’s decision fits into a broader shift in the field, where institutions are increasingly willing to revisit past acquisitions in light of new research and social pressure, whether that involves Nazi looting, colonial plunder, or, in this case, the exploitation of enslaved labor, and the Drake agreement shows how legal tools like long term loans and shared governance can be used to rebalance power without emptying galleries of contested works that carry painful histories.

What the return means for museums and restitution debates

From my perspective, the significance of this case lies in how it widens the frame of restitution debates beyond looted antiquities and wartime seizures to include objects made under coerced labor regimes inside the United States. Coverage of the Boston decision has already described it as a historic move that could influence how other museums handle works by enslaved artists, especially in collections that have celebrated those makers’ creativity without fully grappling with the conditions under which they worked or the families who survived them in the present day.

At the same time, the agreement raises hard questions that the field has only begun to confront, including how to identify legitimate descendant communities, how to handle cases where multiple families claim the same ancestor, and whether institutions are prepared to extend similar recognition to works by other enslaved makers whose names were never recorded, issues that legal scholars and museum leaders are already debating as they study the Drake case and consider how its logic might apply to their own holdings across the country.

Public reaction and the power of seeing restitution in real time

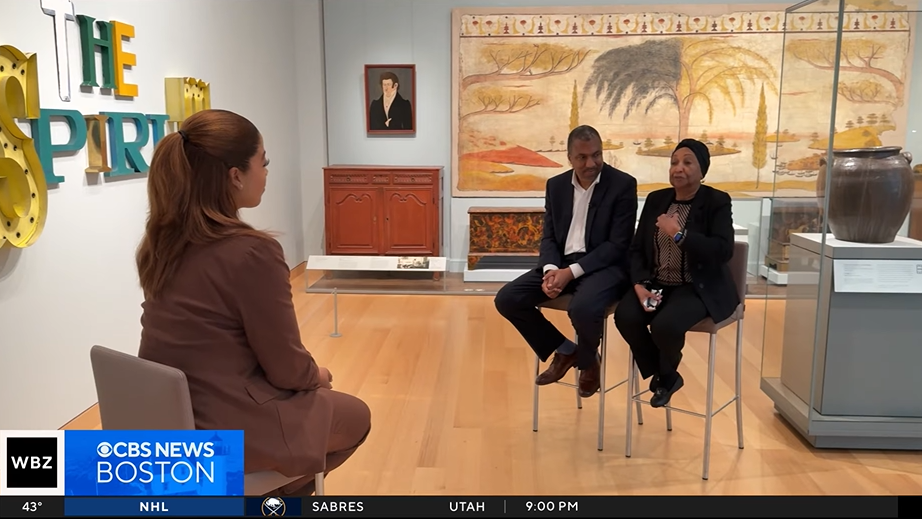

One reason this story has resonated beyond the museum world is that the moment of transfer has been visible, not just described in legal documents. Video shared by museum focused channels shows descendants standing alongside curators and community members as the agreement was announced, with the towering stoneware jars behind them, a visual reminder that these are not abstract assets but physical objects that carry family memory and public meaning at the same time inside the gallery.

Other coverage has captured how the story has been discussed in public forums and interviews, including conversations that situate Drake’s work within a broader movement to recognize the artistry of enslaved craftspeople and to confront the ways their creativity was commodified, and those discussions suggest that seeing a major museum formally acknowledge descendant ownership in real time may embolden more families to come forward with their own claims and more institutions to consider negotiated solutions before conflicts escalate into public standoffs.

More from MorningOverview