The Moon is shifting from a distant backdrop to a very real industrial frontier, with governments and companies racing to stake out the best ice, metals and landing sites. Yet as the hardware improves and launch schedules fill up, the rules that are supposed to govern this new rush remain thin, fragmented and dangerously out of date. I see a widening gap between what is technically possible and what is legally and ethically prepared, and that gap is where conflict, exploitation and environmental damage can easily take root.

From robotic prospectors to crewed missions, the infrastructure for extracting lunar resources is moving from concept art to engineering drawings and flight manifests. The promise is enormous: oxygen for rocket fuel, water for life support, and rare materials for high tech on Earth. But without clear global standards on who can take what, how benefits are shared and how fragile sites are protected, the emerging lunar economy risks repeating the worst habits of terrestrial resource booms, only this time in a place humanity cannot easily repair.

The new lunar gold rush

The most striking change in the past few years is how quickly lunar activity has shifted from exploration to extraction. Australia is preparing a 2026 rover that will use its terrestrial mining expertise to extract oxygen and collect soil on the Moon, a small but symbolic step toward industrial use of the surface that could show how nations might one day mine it. That mission sits alongside a growing list of robotic landers and prospectors being designed specifically to map ice deposits, test extraction technologies and scout locations for future bases rather than simply plant flags.

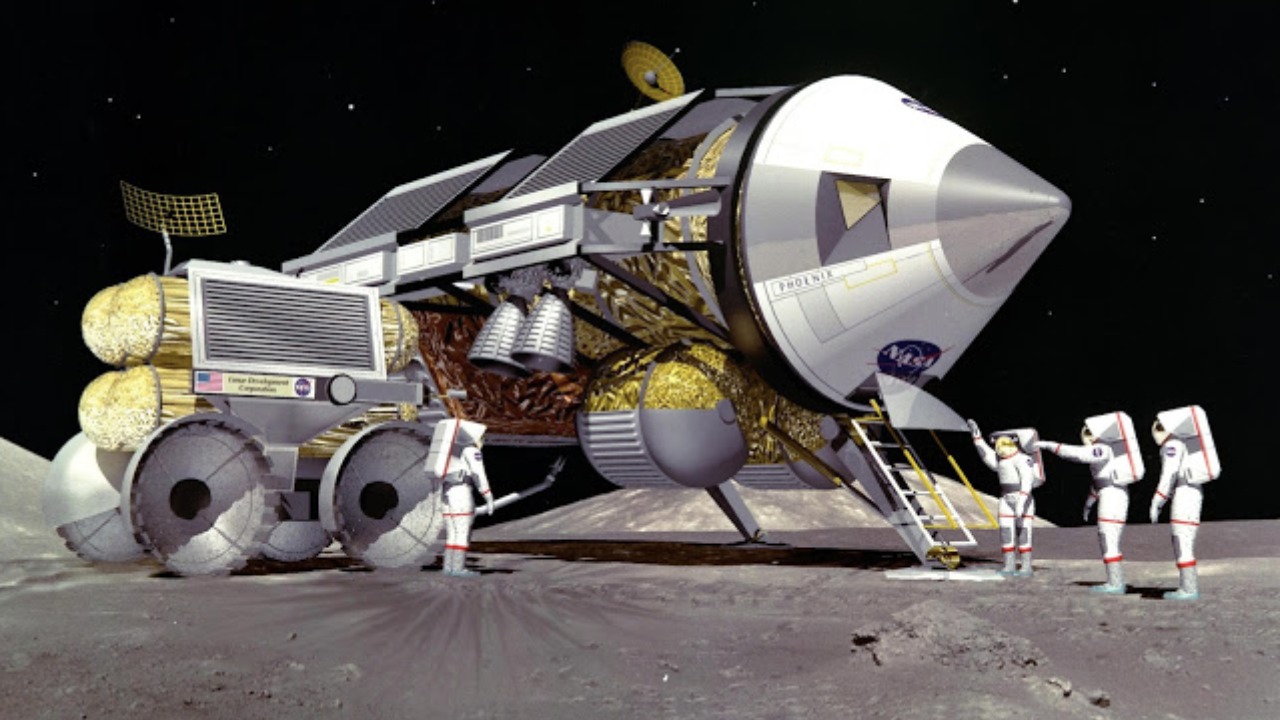

On the heavy-lift side, private launch systems are racing to make the economics of large-scale lunar infrastructure viable. Assuming it overcomes its teething problems, Starship has been described as a potential game changer that could deliver bulky mining rigs, power systems and even modular processing plants to the lunar surface far more cheaply than traditional rockets, turning what was once science fiction into a plausible business plan. The same analysis that highlights Australia’s rover also points to an illustration of an electric rover designed to explore lunar resources, underscoring how quickly concept vehicles are being tailored to prospect and haul material across the regolith using platforms like Starship as their delivery truck.

Frozen treaties in a hot market

While the engineering races ahead, the legal architecture that is supposed to govern space resources is stuck in what one expert calls “Frozen treaties.” The core agreements that shape behavior in orbit and beyond were drafted in the 1960s and 1970s, long before anyone seriously contemplated commercial ice mining or private fuel depots on the Moon, and they say little about how to share benefits at all. That gap is especially stark when compared with the speed at which national agencies and companies are now planning to turn lunar water and regolith into usable commodities, a mismatch captured in the warning that, yet despite evolving technical capabilities, the international legal framework for exploitation has barely moved since those Frozen texts were signed.

That inertia matters because the Moon is not just another mine site, it is a shared environment that every spacefaring nation depends on for navigation, science and future exploration. As the value of lunar ice and metals rises, so does the temptation for states to interpret vague treaty language in self-serving ways, or to rely on national legislation instead of multilateral rules. Yet the more each country improvises its own approach, the harder it becomes to maintain a coherent system that can prevent overlapping claims, protect historic landing sites and ensure that early movers do not lock up the most valuable regions without any obligation to share data or benefits with those who arrive later.

From exploration to extraction: Artemis and beyond

The shift toward resource use is also visible in the flagship crewed programs that are returning humans to lunar orbit and, eventually, the surface. NASA’s Artemis II Mission is scheduled to send astronauts around the Moon in 2026, and in a bid to build public engagement the agency has invited people on Earth to add their names to the flight, with the Artemis II Mission set to Will Carry Over 900,000 Names Around the Moon. That symbolic gesture sits atop a serious technical agenda: testing life support, navigation and reentry systems that will underpin later landings where resource prospecting and in situ use of lunar materials are explicit goals.

Artemis II builds on earlier hardware tests that proved NASA can send large spacecraft around the Moon and back. The agency previously launched the Space Launch System rocket and Orion capsule on an uncrewed test flight around the Moon that lasted about 1 and 1/2 weeks in 2022, a mission that validated the basic architecture for repeated trips to lunar orbit and eventually the surface. NASA had hoped to fly Artemis II sooner, but technical reviews and safety checks pushed the schedule back, a reminder that even as the political and commercial appetite for lunar activity grows, the pace of human-rated missions is constrained by the unforgiving physics and engineering of deep space travel using systems like the Space Launch System and Orion.

Who owns the Moon’s resources?

As missions multiply, the most basic question becomes unavoidable: Who owns the Moon and the stuff in its soil. The Outer Space Treaty makes it clear that no nation can claim to “own” the Moon or any celestial body, a principle that has underpinned decades of cooperative exploration but says little about whether a country or company can take ice, metals or regolith and treat them as private property. In a widely cited discussion of lunar ethics, one section titled “Who owns the moon?” stresses that The Outer Space Treaty will be central to any future lunar mining endeavor, but it also notes that the treaty’s silence on resource extraction leaves room for sharply different interpretations of what is allowed under The Outer Space Treaty.

Some legal scholars argue that extracting and using resources is compatible with the ban on sovereignty, likening it to fishing on the high seas, while others warn that unregulated mining could amount to de facto appropriation of the most valuable regions. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty is also discussed in broader analyses of Legal and Ethical Challenges The Outer Space Treaty, which emphasize that while no nation can claim sovereignty over the Moon, there is growing pressure from industry to clarify whether companies can own and sell resources they extract. That tension is already shaping national laws and commercial plans, and without a shared understanding of what “non-appropriation” means in practice, the risk is that the first big mining operation will set a precedent by force of fact rather than by Legal and Ethical Challenges The.

National laws and a patchwork of rights

In the absence of detailed multilateral rules, several countries have moved ahead with their own legislation to give companies more certainty. The legal landscape for lunar mining rights is now shaped by a combination of international treaties, national laws and emerging commercial practices, with some states explicitly recognizing private rights to resources extracted by their citizens. A recent overview notes that this patchwork is already influencing investment decisions and mission planning, even though there is still no single global mechanism to allocate or enforce rights on a global scale, a gap that leaves the overall system fragile despite the proliferation of lunar mining rights.

Likewise, there are four nations that have passed laws that explicitly say that their citizens and nationals can use lunar resources or space resources, a small but influential club that includes some of the most capable space powers. Those statutes are often framed as clarifying domestic obligations under existing treaties, but in practice they also signal a willingness to move ahead with commercial extraction even before a comprehensive international regime is in place. I see a real risk that as more countries follow this path, the Moon will be governed less by shared rules and more by a race to legislate first and mine fast, with disputes only addressed after the fact through ad hoc diplomacy or litigation shaped by early national laws that, as one legal analysis puts it, already allow companies to Likewise claim use of space resources.

Multilateral efforts: slow, technical and urgent

Despite the national rush, there are serious attempts to build a more coherent global framework, though they are moving at the cautious pace of multilateral diplomacy. Within the United Nations system, a Working Group on Legal Aspects of Space Resource Activities has been tasked with reviewing the existing legal framework and developing recommended principles for such activities, with a key milestone set for 2026 when it plans a Final review and refinement of its summary of discussions and draft guidelines. That process is technical and consensus driven, but it represents one of the few venues where states are openly debating how to balance commercial incentives with obligations to share benefits and protect the lunar environment under the umbrella of Final principles.

Parallel to that legal work, the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space is grappling with the practical side of lunar operations. Its 2026 session is organizing Statements, Meeting Guidelines and Audio requirements for delegations, along with a List of recommended microphones and a Daily Journ that tracks the dense schedule of technical presentations and negotiations. Those details may sound bureaucratic, but they are the scaffolding for discussions on safety standards, debris mitigation and coordination of lunar missions, all of which will shape how mining projects are planned and monitored under the evolving Statements of the STSC 2026 Session.

Competing visions: Moon Agreement vs resource rush

At the heart of the legal debate is a clash between those who see lunar resources as a “common heritage” that should be managed collectively and those who favor a more market driven approach. Article 11 of the Moon Agreement states that the natural resources of the Moon and other celestial bodies in the Solar system are the common heritage of mankind, and it calls for an international regime to govern their exploitation and ensure that benefits are shared. Yet only a small number of countries have ratified that agreement, and major space powers have stayed out, in part because they fear it could limit their ability to control and profit from the resources they obtain from Article of the Moon Agreement.

Instead of relying on international space treaties for legal certainty, inspired by the US, some nations have chosen to develop their own national frameworks to support their lunar exploration and exploitation efforts. That strategy reflects a calculation that it is better to shape norms through practice and bilateral deals than to sign up to a multilateral regime that might constrain future options. I see this divergence as one of the most consequential fault lines in space law: if the Moon Agreement remains marginal while national laws proliferate, the idea of the Moon and other celestial bodies as a shared domain could erode, replaced by a patchwork of overlapping claims and informal spheres of influence that are much harder to reconcile with the original vision of the Instead of approach.

Ethics, workers and the lunar environment

Beyond ownership and sovereignty, there are basic ethical questions about how lunar mining will affect people and the environment. Exposure to cosmic radiation not only carries an increased risk of various cancers but can also affect fertility, and any long term industrial presence on the Moon will have to grapple with how to protect workers from that hazard while also managing dust, isolation and the temptation to push crews to unreasonable hours in unsafe conditions. British astrobiologist Charles S. Cockell has warned that fairness, safety and human rights must be central to lunar planning, arguing that without explicit standards, the harshness of the environment could become an excuse for cutting corners on Exposure related protections.

The environmental stakes are just as high, even if the Moon has no biosphere in the terrestrial sense. Lunar dust is electrostatically charged and abrasive, capable of damaging equipment and potentially harming human lungs if not carefully managed, and mining operations could kick up plumes that travel far from their original sites. There are also cultural and scientific values at risk, from preserving Apollo landing sites to protecting pristine craters that hold records of the early Solar system. A detailed ethical analysis of lunar mining stresses that any future lunar mining endeavor must weigh these factors alongside economic gains, and it frames the question “Who owns the moon?” not just as a legal puzzle but as a test of whether humanity can extend concepts of stewardship and restraint beyond Earth when planning Who will shape those norms.

Geopolitics and the risk of conflict

As more actors eye the same polar craters and resource rich regions, the Moon is also becoming a stage for geopolitical competition. A detailed look at the history of rocketry asks whether space is “the next war-fighting domain” and notes growing concern that military planners are already thinking about how to protect or disrupt critical space infrastructure. That analysis warns that as the Moon race accelerates, there is a real risk of a fight over who lays claim to it, especially if rival powers establish bases or mining sites in close proximity without clear rules on safety zones, data sharing or conflict resolution, a scenario that could turn the lunar surface into a new arena for Is space ‘the next war-fighting domain’?.

Policymakers are not blind to that danger. As efforts to return to the Moon began ramping up in the 2000s, NASA was so concerned by the destructive potential of uncoordinated activity that it pushed for guidelines to protect historic sites and avoid interference between missions. A detailed legal review describes lunar mining as falling into a gray area of international law but notes that talks are underway to avoid conflict, including proposals for notification regimes and safety buffers that could reduce the risk of accidental or deliberate interference. Those discussions are still at an early stage, but they underscore a basic point: without agreed rules, the combination of strategic value and legal ambiguity around the Moon creates a classic recipe for miscalculation, especially as more states and companies treat it as a critical node in their long term space strategies shaped by Moon mining plans.

Can global rules catch up in time?

For all the gaps and tensions, there is still a window to build a more coherent regime before large scale extraction begins. International and national space laws are being revisited in light of new technologies, and some experts argue that the pressure of looming missions could finally push states to clarify how existing treaties apply to resource use. Considering the typically slow pace of multilateral negotiations, a handful of targeted agreements on safety zones, data sharing and environmental baselines might be more realistic in the near term than a sweeping new convention, but the need for some shared guardrails has never been greater as the value of space resources across the Solar system has never been greater, a point underscored in a detailed call for global rules on International and cooperation.

There are also signs that the United Nations is trying to move faster than usual. Right now the United Nations is drafting a Space Resources Treaty, with a release planned for 2027, two years ahead of a broader review of how we peacefully cohabitate and share access to off world resources. That timeline is ambitious by diplomatic standards, and it reflects a recognition that the window for setting norms before the first major mining operations begin is closing quickly. I see the next few years as a decisive test of whether multilateral institutions can adapt to a world where private companies, not just states, are key players in shaping the lunar economy, and whether they can do so in time to prevent the Moon from becoming a legal and geopolitical free for all shaped more by unilateral moves than by a shared Right to use its resources.

More from MorningOverview