For two decades, astronomers have chased a cosmic ghost: ultra‑massive “monster stars” that theory said must have existed but telescopes could never quite pin down. Now the James Webb Space Telescope has delivered the first direct evidence that these titanic objects really lit up the universe’s earliest era, turning a long‑running mystery into an observable fact. The discovery does more than tick a box on a theorist’s wish list, it reshapes how I understand the birth of the first black holes and the chemical foundations of every star that followed.

What astronomers mean by “monster stars”

When researchers talk about “monster stars,” they are not describing slightly oversized versions of the Sun, they are pointing to objects between 1,000 and 10,000 times more massive than it. These hypothetical giants would have formed from pristine hydrogen and helium, with almost no heavier elements, in the universe’s first few hundred million years. For decades, they sat in models as a necessary bridge between the smooth gas after the Big Bang and the surprisingly massive black holes that already existed less than a billion years later, but no one had seen clear observational fingerprints that such extreme stars were real.

In that context, the new Webb results are a turning point because they finally connect those theoretical behemoths to specific galaxies in the distant universe. Earlier work could only infer that something unusual must have powered the intense light and rapid enrichment seen in early galaxies, but it could not distinguish between swarms of ordinary stars and a handful of ultra‑massive ones. By isolating signatures that match stars 1,000 to 10,000 solar masses, the latest analysis gives “monster stars” a concrete identity rather than leaving them as a convenient placeholder in simulations.

How JWST finally caught the giants in the act

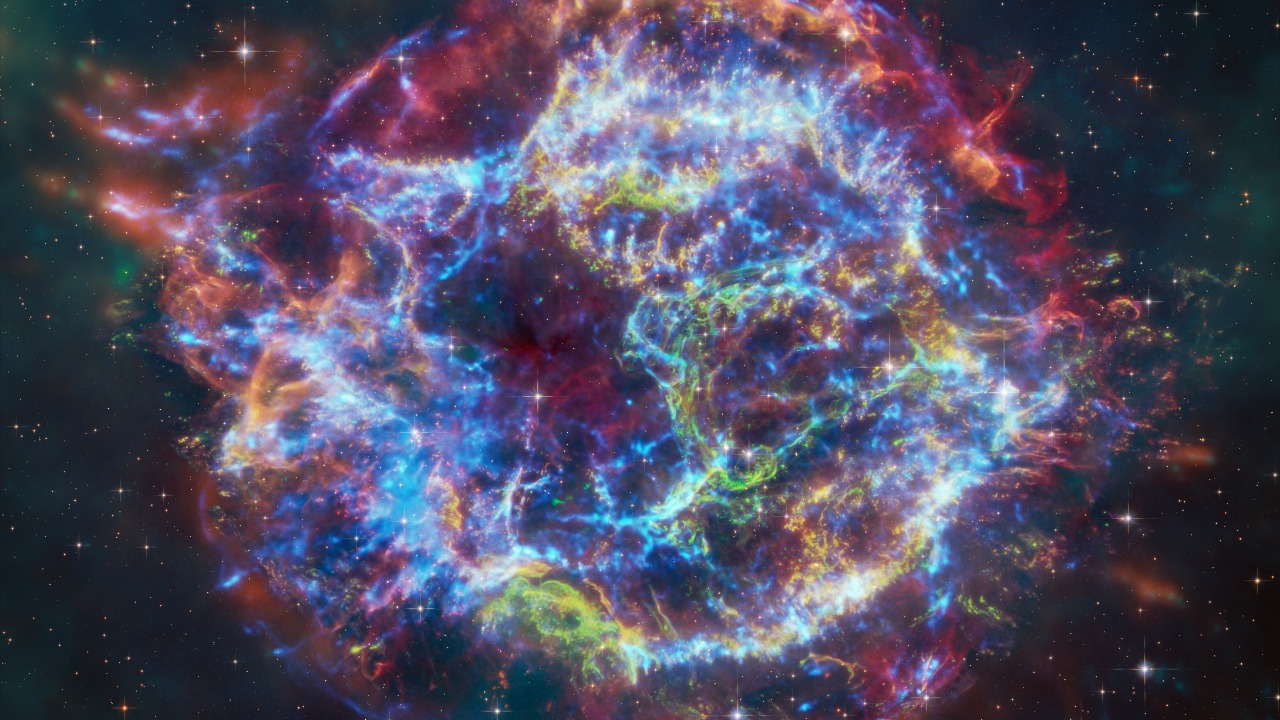

The breakthrough came from the James Webb Space Telescope’s ability to dissect the faint light of galaxies that formed only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. Using NASA’s infrared observatory, a team examined the spectra of these systems and found patterns that could not be explained by normal stellar populations. The data revealed energy outputs and ionization levels that pointed to a small number of extremely hot, extremely massive stars dominating the light, a result that matches long‑standing predictions about the first generation of cosmic giants.

One analysis described how Scientists used the James Webb Space Telescope, often shortened to JWST, to resolve what had been called a 20‑year cosmic mystery about the origin of early black holes. Another report explained that the evidence came from examining the light of very distant galaxies and comparing it with detailed models of stellar populations, work that involved researchers at the Center for Astrophysics and the Institute for Theory and Computation, as described in a separate Scientists account. Together, these studies argue that only a handful of stars thousands of times the mass of the Sun could produce the observed spectral fingerprints in such young galaxies.

From cosmic dawn to “dinosaur‑like” stars

What makes these observations so striking is their timing in cosmic history. The galaxies in question sit at such high redshift that their light left them when the universe was only a few hundred million years old, an era astronomers often call the “cosmic dawn.” In that period, the first stars and galaxies were transforming the intergalactic medium from a cold, neutral fog into an ionized, transparent cosmos. To drive that transformation so quickly, models had long hinted that the earliest stars must have been far more massive and luminous than those forming today.

Recent work has even likened these primordial giants to “dinosaur‑like” stars, ancient and outsized compared with the stellar populations that followed. One team reported that The James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, delivered tantalizing first evidence of these titanic objects in galaxies that were not even 1 billion years old. By catching such systems in the act of blazing with extreme ultraviolet light, Webb effectively opened a window onto a population of stars that had previously been confined to theory papers and computer simulations.

Why normal stars could not solve the black hole puzzle

The existence of supermassive black holes so early in cosmic history has been one of the most stubborn problems in astrophysics. Observations show that by the time the universe was less than a billion years old, some galaxies already hosted black holes with masses of millions or even billions of Suns. If those black holes had grown from the collapse of ordinary stars, accreting matter at typical rates, there simply would not have been enough time for them to reach such enormous sizes.

Researchers at the Center for Astrophysics highlighted this tension by noting that Normal stars could not create such massive black holes quickly enough in the few hundred million years after the Big Bang. Now, using NASA’s James Webb Space Tele instruments, astronomers have found direct evidence that “monster stars” at the cosmic dawn could have collapsed into black hole seeds that were already thousands of solar masses. Those seeds would then need far less growth to become the supermassive black holes we observe in young quasars, neatly closing a gap that had plagued models for years.

Chemical fingerprints: nitrogen, oxygen and the oldest stars

Beyond their role in black hole formation, these giant stars leave behind a distinctive chemical legacy. When they live fast and die violently, they enrich their surroundings with heavy elements forged in their cores. By measuring the ratios of elements such as nitrogen and oxygen in ancient star clusters and distant galaxies, astronomers can infer what kinds of stars must have polluted the gas. Unusual patterns in those ratios have long hinted that something more extreme than typical massive stars was at work in the earliest epochs.

Recent analysis connected these anomalies to what one report called Astronomy findings about the ratio of nitrogen to oxygen in very old stellar populations. The work, associated with Nandal and colleagues and published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, argued that only extremely massive, short‑lived stars could produce the observed chemical signatures. By tying those abundance patterns to the new Webb detections, researchers are building a consistent picture in which monster stars both light up the early universe and seed it with the elements that later generations of stars and planets require.

“Stellar monsters” and the universe’s oldest stars

The emerging consensus is that these monster stars are closely linked to what astronomers call Population III, the very first generation of stars born from pristine gas. These objects would have been metal‑free, meaning they contained virtually no elements heavier than helium, which allowed them to grow to extraordinary masses before radiation pressure blew away their fuel. Their existence has been a cornerstone of theoretical cosmology, but until now, evidence for them has been indirect, inferred from the properties of later stellar populations and the rapid appearance of heavy elements in young galaxies.

New work framed as Stellar “Monsters” May Reveal First Direct Evidence of the Universe’s Oldest Stars connects these giants directly to the earliest stellar populations. The report, which sits under sections labeled Home, Space and Stellar Monsters, describes how Nandal and collaborators used Webb data and detailed modeling to argue that these ultra‑massive stars are the long‑sought first generation. By linking the spectral signatures of distant galaxies to the theoretical expectations for Population III, their work moves the field from speculation toward direct observation of the universe’s first starlight.

Using NASA’s Webb to weigh 10,000‑solar‑mass stars

One of the most challenging aspects of this research is translating faint, redshifted light into concrete estimates of stellar mass. To do that, teams rely on sophisticated models that predict how clusters of stars with different masses and compositions should affect the spectra of their host galaxies. When the observed spectra show extreme ultraviolet output and ionization levels that cannot be matched by any combination of ordinary stars, the models point instead to a small number of ultra‑massive objects dominating the energy budget.

In one widely discussed result, astronomers reported that they had found the first clear evidence that “monster stars” between 1,000 and 10,000 solar masses existed in the early universe, using NASA’s flagship infrared observatory. The summary of that work noted that Using NASA James Webb Space Telescope data, the team showed that only such extreme stars could explain the luminosities and ionization signatures in certain young galaxies. While there are still uncertainties in the exact mass range, the fact that the models require stars far beyond the upper limits seen in the local universe is itself a profound shift in our understanding of what stars can be.

What comes next for monster‑star hunting

For all the excitement around these detections, I see them as the beginning rather than the end of the story. The current evidence is strong but still statistical, based on the integrated light of entire galaxies rather than resolved images of individual stars. Future Webb observations will target more systems at similar and even higher redshifts, looking for consistent patterns in their spectra that can further pin down the properties of these giants. At the same time, theorists are refining models of how such massive stars form, live and die in the turbulent environments of the early universe.

There is also a growing effort to connect these findings with other cosmic probes, from gravitational wave observatories that might one day detect the mergers of black holes born from monster stars to next‑generation ground‑based telescopes that can map the chemical fingerprints they left behind. As more data accumulate, the picture that began with Dec reports of Dec Scientists using The James Webb Space Telescope and continued through Jan discussions of Home, Space, Stellar and Monsters will either solidify into a new standard model of early star formation or force another round of revisions. For now, the universe has finally offered direct proof that its first lights were not modest suns, but true monsters.

More from MorningOverview