Mars has hosted a surprising number of robotic visitors, yet the question of where humans should touch down remains wide open. As engineers refine maps of potential Mars landing sites, one location now dominates the conversation: Jezero crater, the ancient lake basin that has already transformed our understanding of the planet’s habitability. The latest research and rover results suggest that if humanity wants the best mix of safety, science and long-term potential, Jezero stands above the rest.

I see a clear throughline in decades of Mars exploration: every generation of missions has sharpened the criteria for a “perfect” landing zone, and Jezero crater now sits at the intersection of those lessons. From early Viking maps to high resolution orbital surveys and rover traverses, the case for this site has shifted from promising to compelling, with new evidence that it was repeatedly habitable and still holds some of the most tantalizing rocks on the planet.

The long road from Viking maps to precision landing zones

The first serious attempts to chart Mars landing sites were blunt instruments by today’s standards, but they set the template for balancing safety and science. In the era of The Earliest Candidate Viking Landing Sites, mission planners were already wrestling with how to find flat, rock-poor terrain that would not destroy a lander while still offering clues to the planet’s climate and geology. That early process, described as Selecting safe and scientifically interesting locations, relied on coarse imagery and limited topographic data, which forced conservative choices and wide safety margins.

Those constraints shaped where NASA’s first successful landers could go. NASA sent Viking 1 and Viking 2 to relatively bland plains in 1976, prioritizing survival over spectacular geology while still tasking them with imaging Mars and searching for evidence of life. Those missions proved that precision landings on another planet were possible and that the Red Planet’s surface was more varied than anyone expected, but they also highlighted how much more detailed mapping would be needed before riskier, scientifically richer sites could be targeted.

How engineers now score a “good” Mars landing site

Modern site selection is a far more quantitative exercise, and the criteria are unforgiving. Engineers now weigh factors such as surface roughness, slopes, rock abundance, dust, and especially altitude, because Altitude Mars

Latitude is just as critical, because it controls both temperatures and solar power. The same analysis of proposed sites notes that Mars, like Earth, has a range of latitudes that are more favorable for landers, with mid latitude and even equatorial regions offering milder conditions and more consistent sunlight. When I look at the current maps of candidate zones, it is clear that the sweet spot is a band where the atmosphere is thick enough to help with landing, the temperatures are manageable for hardware and humans, and the terrain is neither too dusty nor too jagged for safe operations.

What past rovers taught us about picking the right ground

Every successful rover has effectively been a field test of the landing-site rulebook, and each one has added new constraints. The twin Mars Exploration Rovers were chosen to sample very different environments, and the selection of their sites is still a reference point. A detailed study of the Selection of the Mars Exploration Rover landing sites describes how scientists weighed the climatic and geologic history of locations on Mars where conditions may have been favorable to the preservation of evidence of water, while still meeting engineering limits on slopes and rock hazards.

That logic is visible in the decision to send Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity to Meridiani Planum. Mission scientists picked Meridiani Planum because data from THEMIS showed a region rich in hematite, a mineral that often forms in water, while still offering a relatively smooth surface for the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity to land and drive. That Mission choice paid off when Opportunity found layered rocks and surface materials that recorded a watery past, reinforcing the idea that the best sites are those where orbital data already hint at complex geology tied to liquid water.

From Viking plains to Jezero’s ancient lakebed

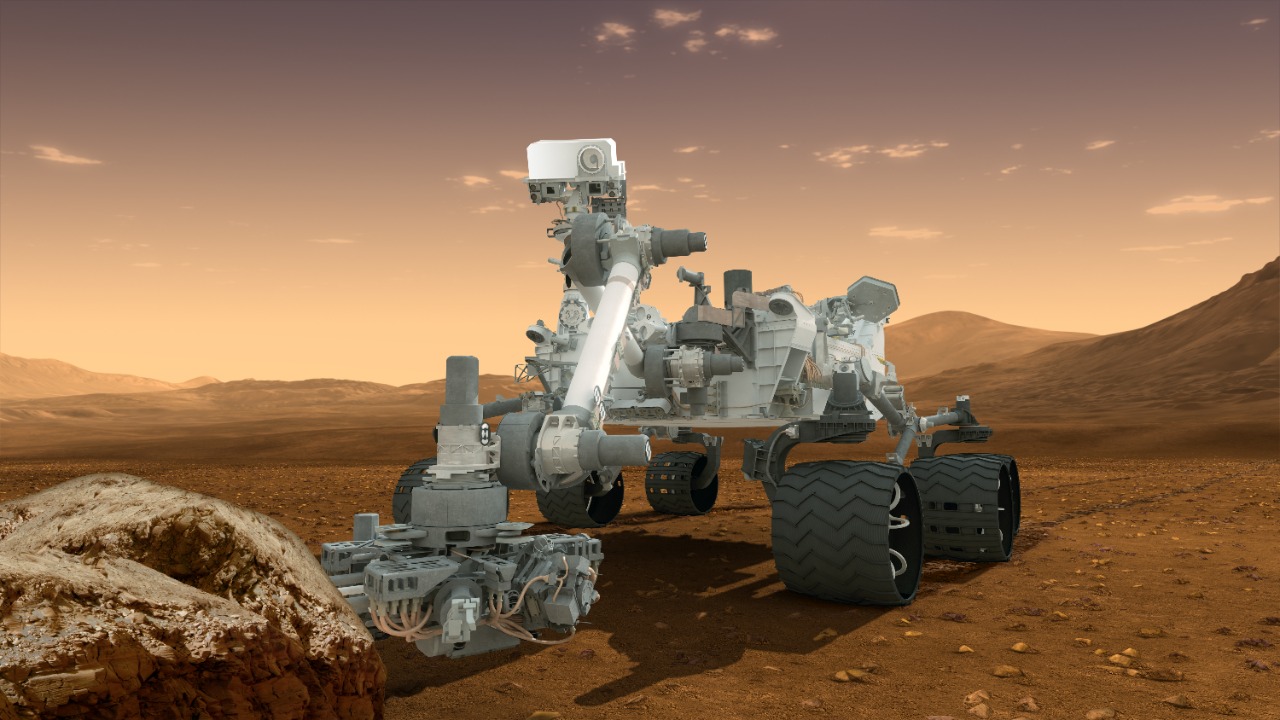

As landing technology improved, mission teams became more willing to accept risk in exchange for richer science, and Jezero crater is the clearest expression of that shift. When Perseverance targeted this site, it aimed for a place where a river once flowed into a lake, depositing sediments that could hold telltale biosignatures. One report on the landing described how But this danger zone, with its cliffs and boulders, was also the perfect spot for the rover to look for signs of ancient microbial life, precisely because of that river delta and its layered deposits.

Subsequent work has only strengthened the case that Jezero was not just briefly wet but repeatedly habitable. New research shows that Jezero crater was once a lake that filled and drained multiple times, creating conditions that were easily habitable later on and potentially preserving biosignatures in different layers of sediment. When I compare that history to the relatively static plains of the Viking sites, the contrast is stark: Jezero offers a dynamic, multi chapter record of water activity that is exactly what astrobiologists have been hoping to find.

Perseverance’s ground truth: why Jezero keeps climbing the rankings

Orbital images can only take planners so far, which is why Perseverance’s traverse has been so influential in reshaping the landing-site map. The rover has already climbed out of the crater floor and up onto the rim, proving that the terrain is navigable and that the geological story is even more complex than expected. When Perseverance Rover Reaches Top of Jezero Crater Rim, the mission team reported that the Perseverance Mars rover had crested the top of Jez crater’s rim, opening a new vantage point on the surrounding landscape and confirming that the route from the floor to the high ground is feasible.

The science has been just as striking. The rover’s analysis of a Martian rock in Jezero Crater uncovered what researchers are calling the clearest sign yet of life on Mars, based on a remarkable combination of minerals, chemistry and textures that are hard to explain without biological processes. While that claim will remain unproven until samples are returned to Earth, it is already influencing how scientists rank potential human landing zones, because any future crewed mission will be under pressure to visit the most promising astrobiological targets first.

Jezero’s hidden volcano and the power question

Jezero’s appeal is not limited to water and potential biosignatures. Recent work has revealed that the crater also hosts a previously hidden volcanic structure, which adds another layer of scientific interest and practical value. One study notes that Mars is the best place we have to look in our solar system for signs of life, and thanks to the Perseverance Rover scientists have identified Jezero Mons, a volcano inside the crater, which could provide crucial context about the timing of water and lava flows. That combination of volcanic and sedimentary rocks in one accessible area is rare and would let future crews study how heat and water interacted over time.

Power is another reason Jezero keeps rising on the list. A global map of Mars Landing Sites for Landers and Rovers Powered by Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators shows how missions that carry their own nuclear power sources can operate in darker, dustier or colder regions than solar powered craft. Jezero sits in a latitude band that is friendly to both solar arrays and Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators, which gives planners flexibility for future human missions that might combine large solar farms with nuclear backup. In practical terms, that means more options for base design and less dependence on any single power technology.

How Jezero stacks up against Gale and Meridiani

To understand why Jezero now looks like the front runner, it helps to compare it with other celebrated landing sites. Gale crater, where Curiosity touched down, has delivered a wealth of evidence that Mars once had the right conditions to support ancient microbial life. From orbit, Gale’s central mound looked like a layered history book, and on the ground Curiosity

Meridiani Planum, for its part, confirmed that sulfate rich sediments and hematite bearing rocks recorded long lasting interactions with water, validating the THEMIS based site selection that targeted those minerals. Yet both Gale and Meridiani lack the clear, river fed lake basin geometry and repeated filling and draining cycles that define Jezero’s history. When I line up the three sites, Jezero offers the most direct path from orbital evidence to ground truth about a standing body of water, a delta that can trap organics, and a nearby volcanic record that can be used to date those events, which is why it now anchors so many discussions about where humans should go first.

Why Jezero’s mapped advantages matter for human crews

Human missions will face constraints that go beyond those of robotic rovers, and Jezero’s mapped features align unusually well with those needs. The crater’s elevation sits in a range where the thin atmosphere of Mars still provides some braking help, avoiding the worst penalties of very high terrain that Higher

Equally important, the diversity of rocks within a short driving radius means that a single base could support a wide range of science campaigns without requiring crews to undertake multi hundred kilometer traverses. The combination of deltaic sediments, lakebed clays and volcanic units around Jezero Mons would let astronauts sample environments that on Earth might be scattered across continents. When I look at the current generation of Mars maps, Jezero crater emerges as the rare site where safety, power, mobility and science all converge, which is why so many planners now see it as the location that stands above the rest.

More from MorningOverview