Mars 3 holds a strange place in space history: it was the first spacecraft to soft-land on Mars, yet its triumph lasted just seconds before silence. The lander managed to transmit a fragmentary image and a burst of telemetry, then its signal cut out after roughly 14 seconds, leaving engineers with a mystery that has lingered for decades. I see that brief contact as one of exploration’s purest cliffhangers, a moment when humanity reached a new world and then immediately lost its voice.

The forgotten first landing on Mars

When people think about the first landing on Mars, they often jump straight to NASA’s Viking missions, but the record actually belongs to a robotic space probe from the Soviet Mars program. The spacecraft known as Mars 3 was part of a broader campaign by the Soviet space program to reach Mars with both an orbiter and a lander, a combined Mars mission that aimed to beat the United States to the surface. The lander survived its descent and touched down intact, which made it the first successful soft landing on the Red Planet, even if its surface operations barely began before they ended.

The achievement has been easy to overlook because the mission’s scientific return was so limited and because the Soviet Mars effort quickly faded from public memory. Yet Mars 3 was a robotic space probe of the Soviet Mars program that pushed hardware, navigation, and communications to their limits at interplanetary distance. Its operator, the Soviet space program, was racing to demonstrate that it could not only reach Mars orbit but also place a functioning lander on the surface, a goal that required threading a narrow engineering needle in an era when even reaching Earth orbit was still relatively new.

A twin mission shaped by failure and urgency

Mars 3 did not travel alone. It was launched just days after its twin spacecraft, part of a series sometimes grouped under the designation Mars M71, which also included an earlier probe that failed to leave Earth orbit and was renamed Kosmos 419. The Mars 2 and Mars 3 missions each carried an orbiter and a lander, a strategy that spread risk but also multiplied the number of systems that could go wrong on the way to Mars. Mars 2’s lander ultimately crashed, leaving Mars 3 as the only chance for a soft landing in that campaign.

The twin design reflected both ambition and urgency. In 1971, the former Soviet Union sent the Mars 2 and Mars 3 spacecraft toward Mars, with each stack consisting of an orbiter plus a lander that would separate shortly before arrival. Each component had to perform flawlessly for the mission to deliver images and data from the surface, and the loss of Mars 2’s lander only increased the pressure on Mars 3’s descent sequence. When Mars 3 survived entry and touchdown, it briefly redeemed the earlier failure, even as its own success unraveled in seconds.

Descent into a global dust storm

The timing of Mars 3’s arrival turned out to be both historic and disastrous. The lander reached the Martian atmosphere during one of the greatest dust storms in recorded history, a planet-wide event that wrapped Mars in a thick, light-scattering haze. The landers in the Soviet campaign had the misfortune to arrive in the middle of this storm, which severely reduced visibility and likely stressed their systems in ways that designers could not fully anticipate on Earth, as later analysis of the Jul reports made clear.

Most scientists agree that the dust storm somehow knocked out the lander’s electrical system, either by inducing discharges, clogging radiators, or overwhelming sensors that were never meant to operate in such extreme conditions. Other theories include mechanical damage during descent or a failure in the communications chain that prevented the orbiter from relaying the signal, but the prevailing view is that the storm was the decisive factor, a conclusion reflected in later assessments that describe how Most scientists saw the environment as the mission’s undoing. In that sense, Mars itself, not just engineering limits, cut the lander’s life short.

Four petals open, 14 seconds of life

On the surface, Mars 3 executed a sequence that had been rehearsed in design labs and test stands for years. After touching down, four triangular petals opened to right the lander and expose its instruments, a mechanical unfolding that transformed the compact entry capsule into a small science station. This was an intricate choreography of pyrotechnic bolts and hinges, and for a few moments it worked exactly as intended, allowing the lander to begin transmitting data back toward its orbiter, as later reconstructions of the landing sequence have described in detail for the period After touching down.

What followed is one of space exploration’s most abrupt endings. The only result received from the surface was a partial image and a short burst of telemetry before the transmission stopped, abruptly and permanently, after roughly 14 seconds. That fragmentary picture, a noisy strip of gray that may show the Martian horizon, is all that remains of the lander’s direct contact with Earth, a fact that has been carefully cataloged in mission histories of Mars 3. In that sliver of data, engineers saw proof that their hardware had reached the surface alive, even as the silence that followed confirmed that its life there was measured in heartbeats.

The ghostly first photo of the Martian surface

The image Mars 3 sent is as enigmatic as its brief transmission. It appears as a series of horizontal lines, with a faint gradient that some interpret as the boundary between sky and ground, but the picture is so degraded that even basic features are hard to confirm. The decimeter transmitter that carried this data had a history of intermittent failures and was used cautiously, with operators prioritizing critical science data before attempting more ambitious imaging, a pattern described in technical notes that explain how Only after key measurements would the system be pushed harder.

Despite its flaws, that first picture has become a touchstone for enthusiasts who see it as the moment Mars 3 briefly opened a window onto the Martian surface. One widely shared discussion of the image notes that Mars 3 was the first successful landing on Mars and that 90 seconds after landing the spacecraft started sending information, including the partial photo, before the signal failed, a timeline that has been repeated in community posts that emphasize the 90 seconds between touchdown and the start of data flow. I find that detail striking, because it underscores how quickly the mission went from triumph to loss, with the image serving as both proof of success and evidence of how little time the lander had.

A tiny rover that never roved

Hidden inside the Mars 3 lander was another pioneering machine that never got its chance: a small walking rover known as PrOP-M. The Mars 2 and Mars 3 landers each carried a PrOP-M rover designed to move across the Martian surface on skis while connected to the lander with a 15 meter (49 ft) long power cable, a concept that would have allowed the rover to explore a modest area around the landing site without needing its own radio link, as described in technical summaries of The Mars 2 and Mars 3 landers. The rover was meant to hop and drag itself along the ground, measuring soil mechanics and obstacles in a way that would foreshadow later, more capable rovers.

Because the lander failed almost immediately, the PrOP-M rover on Mars 3 never deployed, joining the earlier unit on Mars 2, which was destroyed when that lander crashed. In effect, the first rovers on Mars existed only as dormant hardware, their potential cut off by failures in the larger mission architecture. Later overviews of Mars rovers note that the Mars 2 and 3 spacecraft from the Soviet Union carried this early rover concept, and that the Failed Mars 2 landing destroyed its Prop-M with it, underscoring how close the Soviet program came to operating a mobile robot on Mars in the early 1970s. I see that unrealized capability as one of Mars 3’s most poignant what-ifs, a reminder that innovation sometimes arrives before the surrounding systems are ready to support it.

Why the signal died so fast

Explaining why Mars 3 went silent so quickly has occupied engineers and historians for decades. Most reconstructions point back to the global dust storm, which likely reduced solar power, clogged radiators, and may have induced electrical discharges that damaged sensitive components. The consensus that the storm knocked out the lander’s electrical system is reflected in later analyses that describe how Most scientists came to see the environment, rather than a single design flaw, as the primary culprit, even if other theories remain on the table.

There is also the possibility that the communications chain itself failed, either in the lander’s transmitter or in the orbiter that was supposed to relay the signal back to Earth. The decimeter transmitter’s known intermittent behavior, which led controllers to use it sparingly and only after important science data was secured, suggests that the system was operating near its reliability limits, as noted in technical catalogs that emphasize how The decimeter transmitter suffered from intermittent failures. In my view, the most plausible explanation is a combination of harsh environmental stress and marginal hardware, a convergence that left no margin for recovery once the first fault occurred.

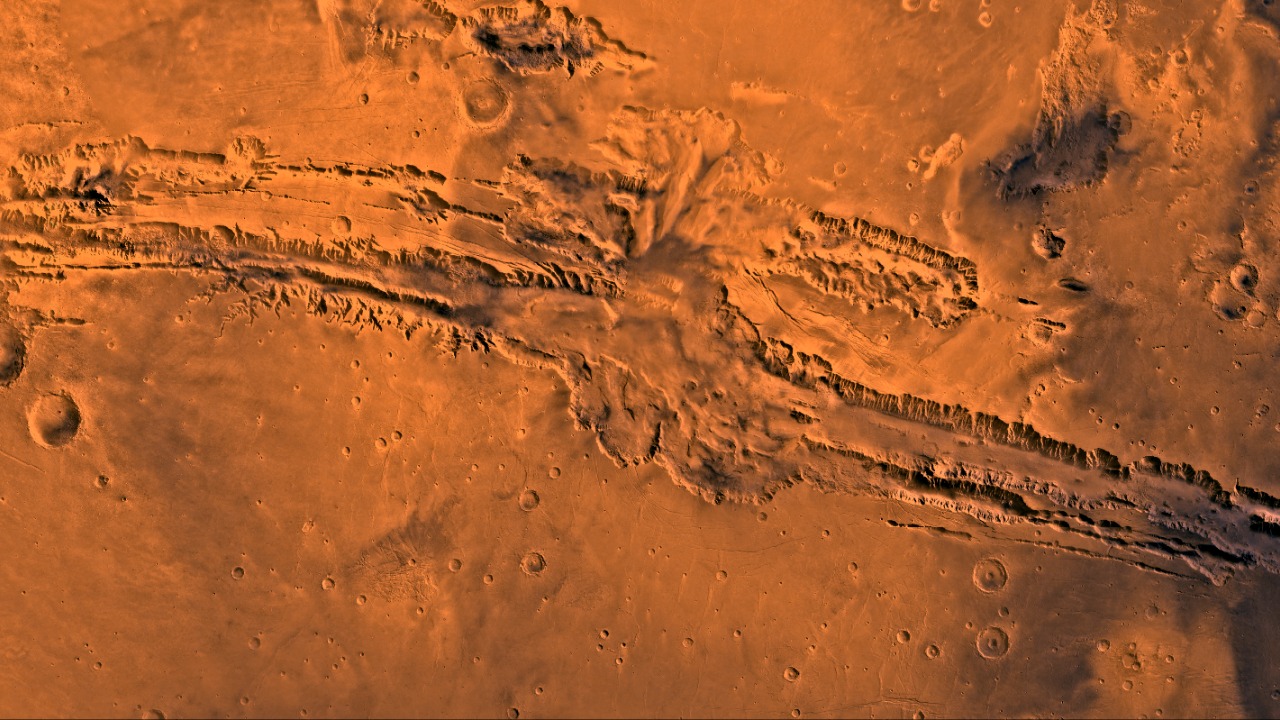

Hunting for the lost lander from orbit

For decades, Mars 3’s hardware was presumed lost, its exact resting place on the Martian surface unknown. That changed when high resolution images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, or MRO, began to reveal small, bright shapes that might match the lander, parachute, and other components. On April 11, NASA announced that the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter may have imaged the Mars 3 lander hardware on the surface of Mars, a claim that grew out of a careful search through publicly available archived images and was later summarized in mission updates that describe how On April the identification effort gained momentum.

The search itself became a cross-continental collaboration between professional scientists and volunteers who combed through MRO’s data. One detailed analysis of the candidate site highlights how the orbiter’s camera captured a cluster of objects that match the expected configuration of the lander’s components, prompting the question of whether this could be the Mars Soviet 3 lander. I find that detective work compelling, because it shows how modern spacecraft can retroactively illuminate the achievements and failures of earlier missions, turning Mars into an archaeological site where the artifacts are pieces of aluminum and fabric scattered across a dusty plain.

Reclaiming a place in Mars history

As new missions from multiple countries head toward Mars, the story of Mars 3 has started to reemerge from obscurity. Commentators have pointed out that the renewed focus on breaking new ground on Mars is also a reminder of one of Soviet scientists’ most disappointing episodes, a moment when a pioneering landing was overshadowed by its own brevity, a perspective captured in retrospectives that note how But the reemphasis on Mars exploration has revived interest in this forgotten mission. In that sense, every new rover and lander that reaches the planet also casts a longer shadow back to the Soviet effort that first touched the surface.

The mission’s anniversary has even become a small point of commemoration in space heritage circles. One recent reflection noted that on this day, 54 years ago, a Soviet spacecraft landed on Mars for the first time, marking how, on December 2, the Mars 3 probe achieved a milestone that still resonates in the language of enthusiasts who describe On December and the figure 54 as a bridge between past and present. I see that growing recognition as a quiet correction to the historical record, one that restores Mars 3 to its rightful place as the mission that proved a soft landing on Mars was possible, even if it could not hold on to that success for more than a few fleeting seconds.

More from MorningOverview