Low doses of a glucagon-like peptide-1 drug, a class better known for reshaping the weight loss market, are now being tested as tools to dial back biological wear and tear in older animals. Early work in mice suggests that carefully calibrated exposure to these compounds can reverse several hallmarks of aging in multiple organs, hinting at a future in which the same molecules used to control blood sugar might also extend healthy years of life. I see a field that is still in its infancy, but already forcing scientists and regulators to rethink what counts as a metabolic drug and what might qualify as an anti-aging therapy.

What the new mouse study actually found

The latest experiment that has captured so much attention focused on older mice given a low dose of a GLP-1 receptor agonist, a drug type that mimics the hormone involved in blood sugar and appetite control. Instead of chasing dramatic weight loss, the researchers set out to see whether a gentler regimen could rejuvenate tissues that typically deteriorate with age, from the brain to the immune system. Reporting on the work describes how the treated animals showed body-wide changes that looked more like those of younger mice, including improvements in metabolic markers and cellular stress responses, while control animals that did not receive the drug continued to show the usual decline associated with late life.

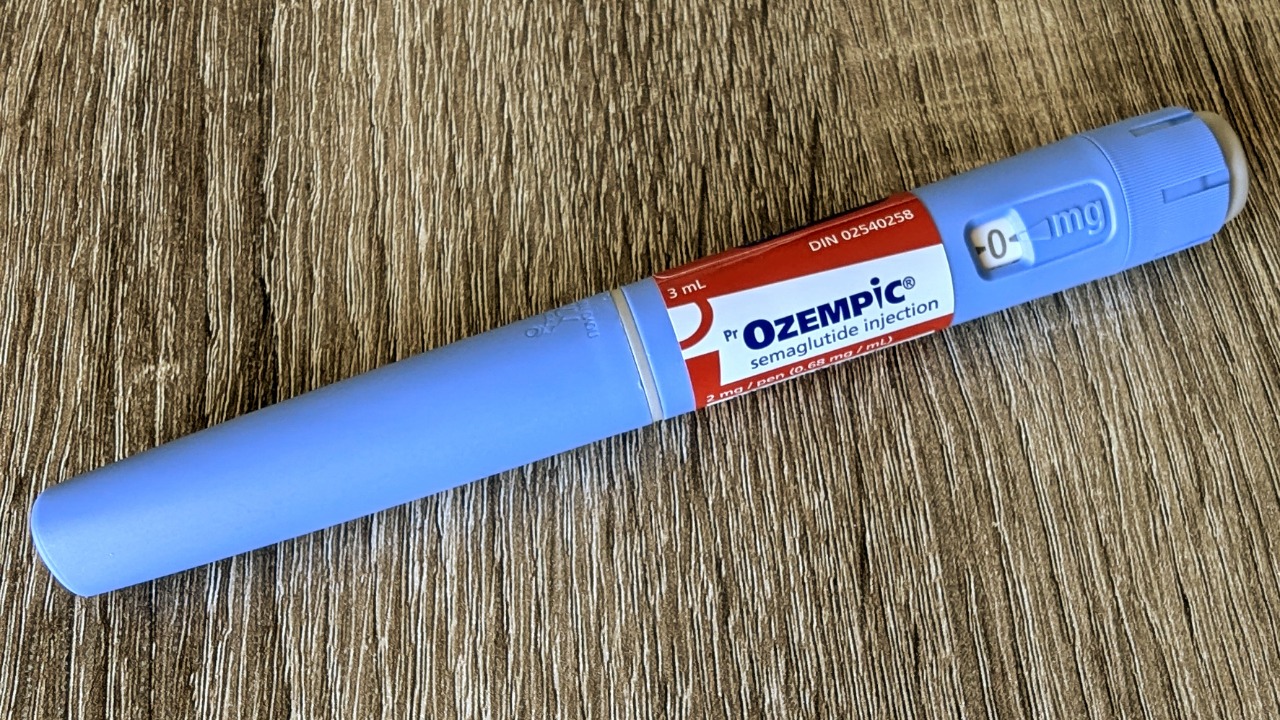

Coverage of the study notes that the intervention was designed around “Low Doses of Ozempic, Like Drug Can Counteract Aging, Older Mice, Study Finds,” with the work framed as News that the same class of medication used for diabetes and obesity might have broader geroscience potential. In that reporting, older mice received the GLP-1 agent while a comparison group simply received a saline solution, allowing the investigators to attribute the observed anti-aging effects to the drug rather than to handling or diet alone. The emphasis on “Low Doses of Ozempic, Like Drug Can Counteract Aging, Older Mice, Study Finds” underscores that the benefit did not require the aggressive dosing often used in weight management, which is an important safety signal if this strategy ever moves toward human trials.

Inside the exenatide experiment and its limits

Another detailed account of the work explains that the team relied on exenatide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist that has been used in humans for type 2 diabetes, to probe how modest stimulation of this pathway might influence aging biology. In that setup, a group of older mice received exenatide while a smaller cohort of nine young mice received the same drug, giving the researchers a way to compare how age at the start of treatment shaped the response. The focus was not just on lifespan, but on markers like inflammation, mitochondrial function, and gene expression patterns that tend to drift in unhealthy directions as animals grow old.

According to a detailed description of the protocol, “A new study published in, nine young mice received exenatide” as part of a broader experiment that also tracked how older animals responded to the same compound, with the work highlighted in Cell Metabolism. That account stresses that the goal was not to push weight to extremes, but to see whether exenatide could reset aging pathways in organs like the liver and brain when delivered at a relatively gentle dose. I read that as a deliberate attempt to separate the drug’s anti-obesity profile from its potential as a geroprotective agent, although the evidence so far remains confined to laboratory animals and cannot be assumed to translate directly to people.

Why GLP-1 drugs are suddenly part of the aging conversation

GLP-1 receptor agonists were developed to help people with type 2 diabetes control blood sugar, and only later did their powerful effects on appetite and body weight turn them into blockbuster obesity treatments. As the new mouse data circulate, researchers are increasingly asking whether these compounds are doing more than trimming fat, particularly in older bodies where metabolic dysfunction and chronic inflammation are tightly linked to age-related disease. The idea is that by nudging the GLP-1 pathway, it might be possible to reset some of the cellular programs that drive frailty, cognitive decline, and cardiovascular risk, even without the dramatic weight loss that has dominated headlines.

A comprehensive scientific review labeled “SUMMARY” of “GLP” receptor agonists argues that these drugs provide proven and potential benefits that may help people experience a prolonged healthy lifespan, with the authors explicitly stating that they “may” expand healthspan as societies grapple with the aging human population. That assessment, which appears in section 4, “SUMMARY” of a technical paper on GLP biology, pulls together evidence from cardiovascular outcomes trials, kidney studies, and early cognitive research to suggest that the class could influence multiple organ systems that matter for aging. I see the new mouse work as a mechanistic complement to that broader clinical picture, offering a controlled glimpse into how low-dose GLP-1 stimulation might reprogram aging tissues in ways that align with the human data on reduced heart and kidney events.

How geroscientists are framing the stakes

Within the aging research community, GLP-1 drugs are now being discussed as part of a larger push to find interventions that target the biology of aging itself rather than any single disease. A policy and science brief dated Feb 20, 2025, titled “GLP-1 Drugs, Population Health and Aging: A New Frontier?” captures this shift, noting that “GLP-1s for anti-aging… in mice” are already being tested and that the field is moving quickly to interpret those findings. The authors of that document argue that if GLP-1 receptor agonists can indeed slow or reverse aging processes, they could reshape not only clinical practice but also how health systems plan for older populations.

In that same Feb 20, 2025 analysis, the researchers cite the preprint identifier “10.1101” and the date fragment “05.06” to anchor their discussion of early-stage mouse data, and they explicitly refer to “Feb” and “GLP” as they sketch out scenarios for how these drugs might be deployed at scale. The brief, available through a geroscience policy center at USC and UCLA, frames GLP-1 receptor agonists as a potential bridge between metabolic medicine and longevity science, while also warning that the evidence is still heavily weighted toward animal models and short-term human outcomes. By linking the emerging mouse work to that broader policy conversation in Feb, I see a clear signal that geroscientists are preparing for a future in which regulators may be asked to consider aging itself as a treatable target, with GLP-1 drugs among the first candidates.

Body-wide anti-aging signals in older animals

One of the most striking aspects of the new data is that the benefits appear to be distributed across the body rather than confined to a single organ. Reporting on the study describes how treated animals showed improvements in multiple tissues, including metabolic organs and the nervous system, suggesting that GLP-1 signaling might be tapping into a shared aging program. For geroscience, that matters because the field has long sought interventions that can shift several hallmarks of aging at once, rather than simply delaying one disease while leaving others untouched.

A widely shared summary of the findings highlights that “New study, Mice treated with GLP1s saw body-wide anti-aging effects” and emphasizes that “Notably, the effects were present in older mice” that had already accumulated substantial biological damage. That description, which circulated on social media on Nov 19, 2025, underscores that the intervention did not need to start in youth to show benefit, a key consideration for any therapy that might eventually be offered to people already in their sixties or seventies. The same post, which labels the work as a “New” development and calls out “Mice” and “Notably” in its framing, has helped push the idea of body-wide rejuvenation into the public conversation, even though the underlying data remain preclinical and are summarized in a single New image rather than a full peer-reviewed article.

From viral headlines to cautious interpretation

As coverage of the study has spread, the story has often been framed around the familiar brand names that dominate the weight loss conversation, especially Ozempic and its cousins. One widely read piece, dated Nov 20, 2025, describes how “Low Doses of Ozempic-Like Drug Can Counteract Aging in Older Mice, Study Finds,” presenting the work as a potential turning point in how these medications are perceived. The article notes that the research was published in the journal Cell Metabolism and that the drug used was similar to Ozempi, a detail that has fueled speculation about whether existing prescriptions might already be nudging aging pathways in patients who take them for diabetes or obesity.

The same Nov 20, 2025 report stresses that the animals received a relatively modest dose and that the goal was to observe anti-aging effects rather than extreme weight changes, a nuance that can get lost when the story is reduced to social media shorthand. By highlighting “Nov” and “Cell Metabolism” alongside the reference to “Ozempi,” the coverage grounds the findings in a specific scientific context while still acknowledging the cultural weight of these drugs. I read that as an attempt to balance excitement with restraint, and it is reflected in the way the story on Nov 20, 2025 walks readers through the experimental design before turning to the broader implications.

What this could mean for human aging, and what remains unverified

For people watching the GLP-1 boom from the sidelines, the idea that the same class of drugs might slow aspects of aging is both tantalizing and unsettling. On one hand, the mouse data suggest that low-dose regimens can influence multiple hallmarks of aging, from inflammation to cellular stress responses, in ways that line up with what clinicians already see in cardiovascular and kidney outcomes among human users. On the other hand, the leap from a controlled mouse experiment to a real-world anti-aging therapy for people is enormous, and there is no direct evidence yet that low-dose GLP-1 treatment can safely extend healthspan in humans beyond the benefits already documented for diabetes and obesity.

Some commentators have framed the new findings as proof that the weight loss revolution is quietly doubling as a longevity revolution, but that narrative moves faster than the data. A more measured account of the study, which describes how “Low Doses of Ozempic-Like Drug Can Counteract Aging in” older animals and situates the work within the broader future-society debate, reminds readers that the evidence so far is confined to mice and that long-term human trials focused explicitly on aging outcomes do not yet exist. That perspective, laid out in a detailed feature on future-society implications, underscores that many key questions remain unverified based on available sources, including whether similar low-dose strategies would be safe for older adults with multiple chronic conditions and how regulators might evaluate aging as a formal indication. As I see it, the most responsible way to read the current evidence is as a promising signal that GLP-1 biology intersects with aging, not as a guarantee that a simple injection will let humans rewind the clock.

More from MorningOverview