Light is quietly becoming the new language of brain technology. Instead of thick wires and skull-penetrating electrodes, a new generation of implants uses tiny LEDs and optical sensors to send information directly into neural tissue, teaching the brain to interpret flashes of light as meaningful signals. The result is a radical rethink of how I can imagine brain-computer interfaces working, with devices that are smaller than a grain of salt and soft enough to slip under the scalp while still delivering rich data streams in both directions.

What is emerging from these experiments is not just a cleaner way to stimulate neurons, but a full optical channel into the cortex that can encode patterns, restore sensations, and potentially power long-term prosthetics. By combining microelectronics, optogenetics, and wireless power, researchers are starting to show that the brain can learn to treat artificial light patterns as if they were touch, sound, or other natural inputs, opening a path to implants that feel less like hardware and more like a new sensory organ.

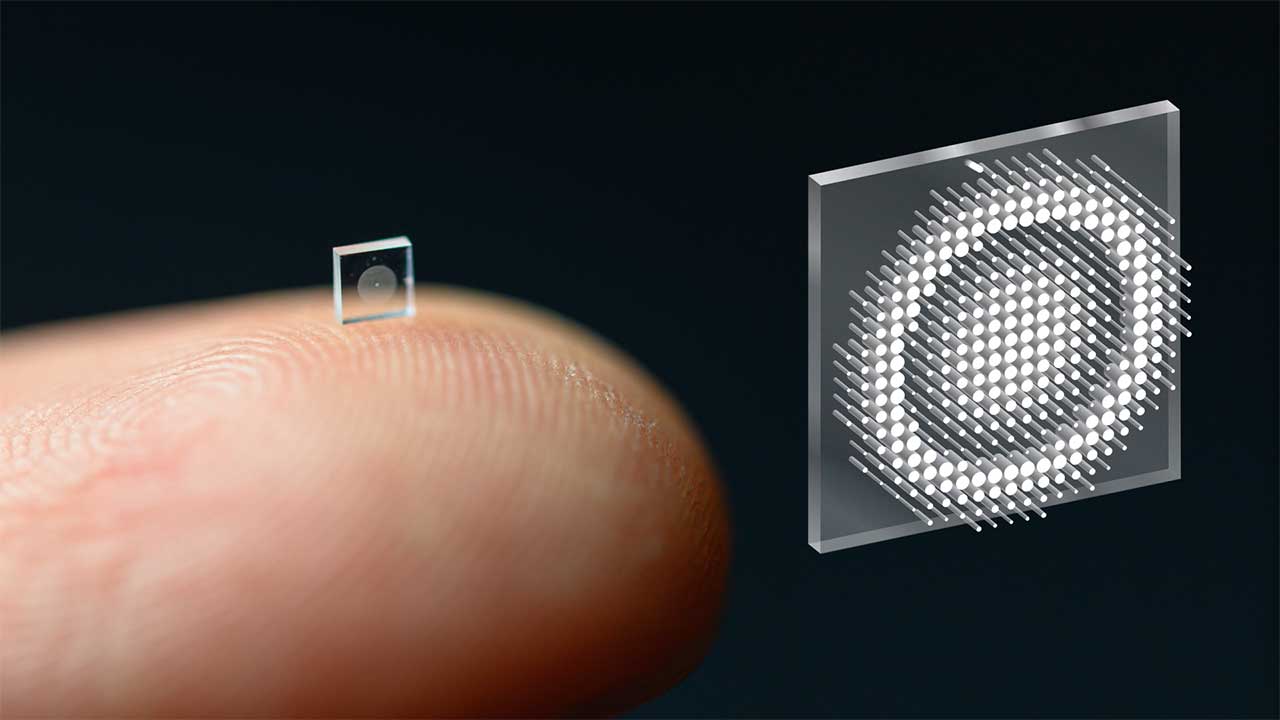

From salt grain to signal: how tiny optical implants work

The most striking proof of concept comes from a neural implant so small it can literally sit on a grain of table salt, yet still record and transmit brain activity. In work led by Nov researchers at Cornell and collaborators, the device uses a semiconductor diode made of aluminum gallium arsenide to capture red and infrared light from outside the body, convert that energy into power for its circuit, and then emit its own light to communicate neural data back out of the brain. The implant rests on the surface of the cortex and tracks how the brain processes sensory information from whiskers in mice, turning subtle neural voltage changes into optical signals that can be read wirelessly through the skull, as described in the team’s neural implant smaller than salt grain report.

Another account of the same Nov breakthrough emphasizes just how radical this shift to light really is. Instead of relying on radiofrequency antennas or bulky batteries, the implant uses light to record and transmit brain signals and works with minimal scarring in mice, which is crucial for any device that might stay in place for months or years. As the animals’ whiskers flitter, the implant captures the resulting neural activity and relays it optically, showing that a device smaller than a grain of sand can still deliver stable recordings over long periods, a capability highlighted in coverage of This Wireless Brain Implant Is Smaller Than a Grain of Salt.

Teaching the brain a new language of light

Recording is only half the story, though. In parallel with these salt-grain devices, another group has built a fully implantable system that sends light into the brain as a kind of secret code, training neural circuits to interpret artificial flashes as new sensations. Researchers behind this Light, Based Brain Signal project created a soft wireless brain implant that delivers patterned light into cortical tissue, and over time, the brain learns to read those patterns as meaningful input. The device is designed to be fully implantable and to operate without tethering cables, which makes it a plausible platform for next-generation prosthetics and new therapies that rely on stable, long-term stimulation, as detailed in a report on a soft wireless brain implant that sends light as artificial sensations.

What makes this approach so powerful is that it treats the brain as a learning system rather than a passive receiver. Instead of simply turning neurons on and off, the implant delivers specific light patterns across multiple cortical regions, and animals are trained to associate those patterns with particular cues or rewards. Over repeated trials, the cortex begins to treat the optical code as if it were a natural sensory signal, effectively expanding the brain’s vocabulary. This shift from crude stimulation to programmable information delivery is central to the idea that light-based implants can one day restore lost senses or add entirely new channels of perception.

Northwestern’s soft micro-LED array that “speaks” through the skull

The most advanced demonstration of this concept so far comes from Northwestern scientists who developed a soft, wireless micro-LED implant that sits under the scalp and sends information straight into the brain using light. In their experiments, a flexible array of tiny LEDs delivered precise light patterns through the skull, allowing mice to learn tasks based solely on those optical cues, without any sound or traditional sensory signals. The device is thin and compliant enough to conform to the skull, yet powerful enough to activate neurons through bone, which is why the team describes it as a leap in how a device can wirelessly speak to the brain with light.

Follow-up reporting on the same work underscores that this is not just about turning neurons on, but about encoding structured information. Going beyond the ability to activate and deactivate a single region of neurons, the new device features a programmable micro-LED array that can deliver distinct spatial and temporal patterns across four cortical regions at once. In a series of trials, the implant delivered a specific pattern across those four regions, and the mice learned to interpret that pattern as a behavioral cue, showing that the cortex can decode complex optical messages delivered through the skull, a capability described as Going beyond the ability to simply flip neurons on and off.

Year-long recordings and the promise of stability

For any brain-computer interface to be clinically useful, it has to last. Here, the tiny optical implants are starting to show staying power that rivals or exceeds traditional electrodes. In a Nutshell summary of the salt-grain device notes that Scientists created a wireless brain implant smaller than a grain of sand that recorded neural activity in mice for an entire year, without the kind of signal degradation that often plagues metal-based arrays. The implant’s ability to operate wirelessly and maintain stable recordings over such a long period suggests that optical power and communication can dramatically reduce mechanical stress and scarring, as highlighted in coverage of a Brain Implant Smaller Than A Grain Of Sand that records neural activity.

The Northwestern team’s optical stimulator is also built with longevity in mind. Their Implant is described as soft and wireless, designed to minimize friction with surrounding tissue and to avoid the rigid anchors that can cause inflammation over time. The researchers frame The Problem as Restoring lost senses or providing sensory feedback for prosthetic limbs, which demands a device that can sit under the scalp for years without frequent surgical revisions. To that end, they emphasize sensor design and materials that match the mechanical properties of skin and bone, as detailed in their description of an Implant built to address The Problem of Restoring sensory feedback.

Engineering the micro-LED arrays that make light talkative

Behind the scenes, the hardware that makes all of this possible is a carefully engineered micro-LED array that can both survive in the body and deliver precise optical patterns. In a technical overview shared by Northwestern, the team highlights how a Micro-LED Array Enables Brain communication by integrating dozens of tiny emitters on a soft substrate that can flex with the skull. The design balances brightness, heat, and power consumption so that the LEDs can activate neurons without damaging tissue, and it relies on wireless power transfer so that no physical connectors pierce the skin, a configuration illustrated in their description of a Micro-LED Array Enables Brain interface.

Other reports emphasize that the implant is placed just under the scalp, not deep in the brain, and uses light to speak to genetically modified neurons in brain tissue that have been made sensitive to specific wavelengths. This tiny BMI is described as minimally invasive, relying on a thin device placed under the scalp that sends light through bone to reach modified neurons in brain tissue, rather than inserting rigid probes into the cortex itself. That approach reduces surgical risk and opens the door to outpatient procedures, as explained in coverage of a tiny device placed under the scalp that uses light to speak to the brain.

Behavioral learning: when mice follow light instead of sound

The real test of any information channel into the brain is whether it can guide behavior, and here the optical implants have delivered some of their most compelling results. In one set of experiments, a soft, wireless implant developed at Northwestern used a micro-LED array to send light patterns through the skull, letting mice learn tasks in which no physical sensation, smell, or sound cues were involved. The animals were trained to respond to specific light codes delivered directly to their cortex, and over time they behaved as if those codes were ordinary sensory instructions, a finding described in detail in a report on a soft, wireless implant that sends information straight to the brain using light.

Another account frames the same work in more futuristic terms, inviting readers to imagine sending information straight into the brain without wires, surgery, or sound. In that Overview Imagine scenario, scientists develop a tiny brain implant that wirelessly transmits secret signals and uses light to “talk” directly to neurons, bypassing the usual sensory organs. The device is portrayed as a proof of concept for a brain-machine interface that could one day deliver instructions, alerts, or even complex data streams directly into neural circuits, as summarized in a video feature on Overview Imagine sending information straight into the brain.

Minimally invasive implants and lessons from other prosthetics

One reason these optical systems are attracting attention is that they align with a broader shift in brain-computer interface design toward minimally invasive procedures. A recent BCI milestone described in a peer-reviewed study highlights how a new interface can be rapidly implanted through a minimally invasive procedure, avoiding the need for open-skull surgery while still achieving high-bandwidth communication. That work underscores a growing consensus that for BCIs to scale beyond a handful of patients, they must be safe, quick to implant, and compatible with standard clinical workflows, a trend captured in analysis of a Breakthrough Brain-Computer Interface Is Minimally Invasive.

Outside the brain, similar design principles are reshaping how other implants interact with nerves. In dental research, for example, engineers have developed a new implant and minimally invasive technique that should help reconnect nerves, allowing the implant to “talk” to the surrounding tissue more like a natural tooth. The approach uses materials similar to those used in hip replacements or fracture repair, but combines them with nerve-guiding structures so that the body’s own fibers grow into the implant, as described in a report on a new implant and minimally invasive technique that could make dental implants feel more like real teeth. I see a clear parallel: whether in the jaw or the cortex, the goal is to create hardware that the nervous system can adopt as its own.

What light-based brain interfaces could mean for future therapies

Put together, these advances point toward a future in which light-based implants are not exotic lab tools but practical platforms for therapy. The Light, Based Brain Signal work shows that a fully implantable device can send patterned light into neural tissue and teach the brain to interpret it as artificial sensation, suggesting a path to prosthetic limbs that provide rich feedback or visual aids that encode spatial information as tactile-like signals. The Northwestern micro-LED array demonstrates that a soft, wireless device can sit under the scalp and deliver complex optical codes through the skull, which could be adapted to restore lost senses or provide continuous guidance to people with sensory processing disorders, as described in their Nov announcement of a neural implant smaller than a salt grain that wirelessly tracks brain activity.

At the same time, the salt-grain implants from Nov Cornell and the year-long recordings described in the Nutshell summary show that optical power and communication can support stable, chronic monitoring without the scarring and signal loss that have limited many electrode-based systems. Combined with minimally invasive BCI procedures and nerve-reconnecting techniques from dental and orthopedic research, these developments suggest that future brain implants could be smaller, softer, and more integrated with the body than anything in use today. I see the shift to light not just as a technical upgrade, but as a conceptual one: instead of forcing the brain to adapt to rigid hardware, engineers are learning to speak the brain’s own language, one photon at a time.

More from MorningOverview