The James Webb Space Telescope has turned its infrared gaze on the early universe and found something that should not quite exist: compact objects that look like stars in a telescope image but behave like fully fledged galaxies in the data. Astronomers have nicknamed them “platypus galaxies,” a nod to the way they mash together traits that normally do not appear in the same place or time. Whether they are simply very young galaxies caught in a fleeting phase or a genuinely new class of cosmic structure, they are already forcing a rethink of how the first star systems came together.

At the heart of the mystery is a small sample of nine objects that sit only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, yet shine with the kind of organized star formation usually associated with much more mature systems. I see in these findings a stress test for our standard picture of galaxy evolution, one that Webb’s unprecedented sensitivity was always likely to deliver but whose details are stranger than most astronomers expected.

What makes a galaxy a “platypus”?

The nickname is more than a cute metaphor. Just as the animal platypus combines a duck’s bill, a beaver’s tail, and mammalian traits in one body, these galaxies blend properties that theory normally keeps separate. In Webb’s sharp images they appear as tiny, pointlike specks, the way individual stars usually do, yet their spectra and brightness reveal the complex, distributed star formation typically seen in full galaxies. That odd pairing led researchers to describe them as astronomy’s own platypus, a label that captures how they defy the usual checklists used to classify distant objects.

According to work led by University of Missouri astronomers, the nine sources sit at extreme distances, so we see them when the universe was only a small fraction of its current age of 13.8 billion years, yet they already host vigorous star formation more typical of later epochs. Another analysis that describes them as astronomy’s platypus emphasizes that, on the one hand, they resemble compact star clusters, while on the other, their light output and chemical fingerprints line up better with small galaxies. That mismatch is exactly what makes them so valuable: they occupy a gray zone that standard categories gloss over.

How Webb uncovered nine bizarre baby systems

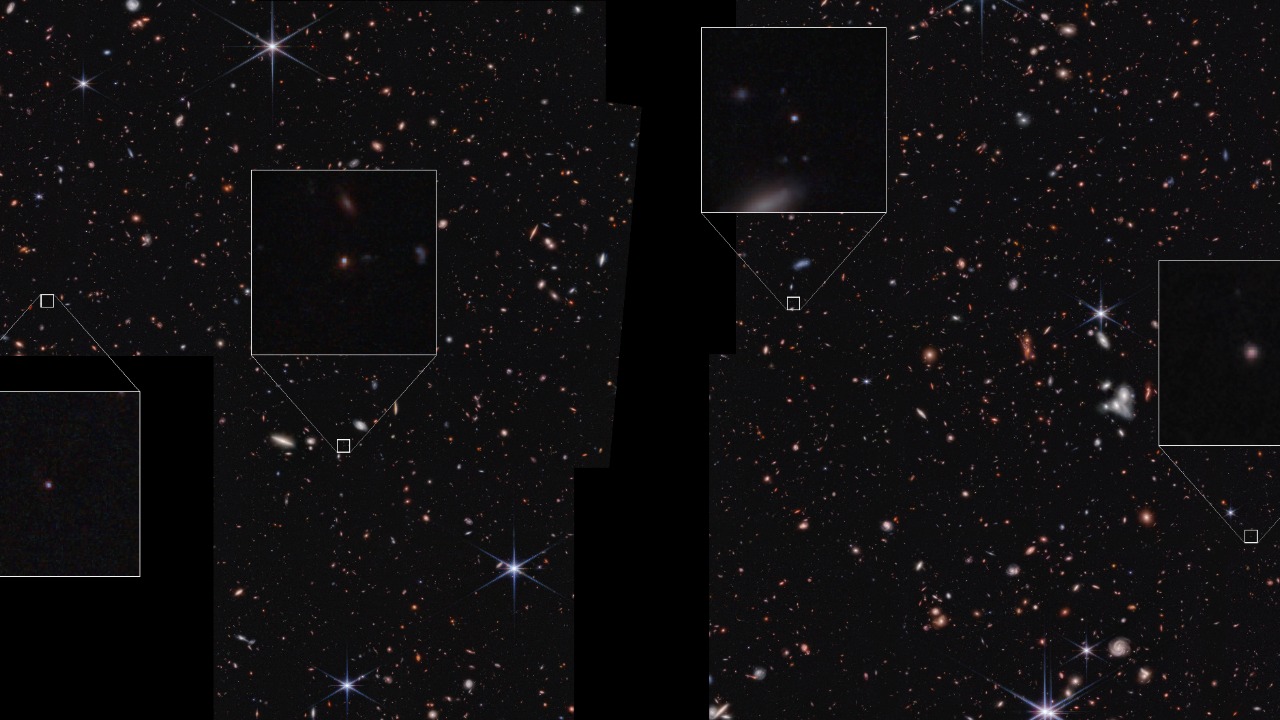

To find such elusive objects, astronomers leaned on the core strengths of the James Webb Space Telescope, whose infrared instruments are designed to capture faint, redshifted light from the first generations of stars. By scanning deep fields and then combing through archival observations, teams identified sources that were unusually bright for their apparent size and distance, then followed up with spectroscopy to decode their internal activity. The result was a shortlist of nine candidates that refused to fit neatly into existing models of early galaxies or star clusters.

Researchers at the University of Missouri describe these nine objects as looking like stars but behaving like galaxies, with a mishmash of parts that includes compact cores and extended regions of star formation. Other astronomers, using independent datasets, have reported similarly puzzling sources in Webb’s deep surveys, reinforcing the idea that these are not one-off oddities but part of a broader population. The telescope’s mission profile, outlined by NASA, always anticipated discoveries in this regime, but the sheer strangeness of these particular systems has surprised even seasoned observers.

Why they defy standard galaxy evolution

In the standard picture of cosmic history, small clumps of dark matter and gas gradually merge and grow, forming the first stars in scattered pockets before settling into more organized galaxies. The platypus candidates seem to skip some of that messy adolescence. They are compact, as if they were still embryonic, yet they already show the kind of sustained, large-scale star formation that theory usually reserves for more massive, evolved systems. That combination suggests either that galaxy assembly can proceed far more rapidly than expected or that we are seeing a different evolutionary pathway altogether.

Analyses of Webb data indicate that four of the nine galaxies in the newly identified sample sit at very high redshift, close to the era when the first light in the universe was turning on, yet they already display strong emission lines associated with intense star formation, a result highlighted in the new analysis of how they challenge models of galaxy formation and evolution. Another team, presenting results under the banner As Puzzling As a platypus, notes that these hard to categorize objects were discussed at a major meeting and that one of the key metrics, the number 44, appears in the context of their observational parameters. I read that as a sign that the community is already probing their detailed properties, from luminosity functions to line strengths, to see exactly where they sit relative to known populations.

Baby galaxies or a brand-new class?

The central debate now is whether these systems are simply very young galaxies caught at a transitional moment or whether they represent a fundamentally different kind of object. Some astronomers argue that they might be dense star clusters embedded in larger, faint halos that Webb has not fully resolved, which would make them extreme but not unprecedented. Others point out that their luminosities and inferred masses are too high for typical clusters, hinting that they could be the seeds of future galaxies or even an entirely new category of compact, star-forming systems that dominated the earliest epochs.

Reports describing platypus galaxies emphasize that astronomers say they cannot categorize them, they are so odd, which underscores how far they sit from familiar templates. Social media posts from Scientists using Webb data stress that, like the animal, these objects remain unusual even as more candidates appear. Another commentary notes that strange cosmic objects spotted by the James Webb Space Telescope may be baby platypus galaxies or something entirely new, capturing the uncertainty that still surrounds their true nature. I see that ambiguity as productive: it forces theorists to confront whether their models can accommodate such hybrids without inventing ad hoc fixes.

What these hybrids mean for the next decade of Webb

Whatever label ultimately sticks, the discovery of these platypus-like systems is a preview of how transformative Webb’s long mission could be. Each time astronomers push to higher redshift or lower luminosity, they are likely to uncover more objects that blur the lines between categories, from proto-galaxies to nascent star clusters and perhaps even the first black hole seeds. The key will be building statistically robust samples, then tracking how their properties change with cosmic time, so that individual curiosities become part of a coherent evolutionary sequence.

Commentary shared by Strange reports highlights that some astronomers see these objects as exactly the kind of surprise Webb was built to find, while others caution that more data are needed before rewriting textbooks. A separate note from Astronomers suggests that a new kind of galaxy may have been hiding in plain sight in archival Jam data, implying that similar hybrids could already be lurking in existing observations. As I see it, the platypus galaxies are less an endpoint than a starting signal: proof that the early universe still holds categories we have not yet named, waiting in the infrared glow for Webb and its successors to reveal.

More from Morning Overview