Hints of life may have just flickered into view from a world 124 light-years away, and the signal is coming through the James Webb Space Telescope. The exoplanet K2-18b, a so-called Hycean candidate with a possible global ocean wrapped in hydrogen, now sits at the center of a high-stakes debate over whether Webb has captured the first credible chemical fingerprints of biology beyond the Solar System. The evidence is tantalizing, but as I see it, the story of K2-18b is as much about scientific caution as it is about cosmic possibility.

What Webb actually saw on K2-18b

The excitement around K2-18b rests on a specific set of molecules that researchers say they have teased out of the planet’s starlight. When the world passes in front of its red dwarf star, the James Webb Space Telescope measures how different wavelengths are absorbed by the atmosphere, revealing a spectrum that can be matched to known gases. In the case of K2-18b, teams reported signatures of methane and carbon dioxide, along with a possible hint of dimethyl sulfide, a compound on Earth that is strongly associated with marine microorganisms and other biological activity, all consistent with a planet that may host a deep ocean beneath a hydrogen-rich sky.

Earlier work with Hubble had already suggested that K2-18b contains water vapor and carbon-bearing molecules, and Webb’s more precise instruments have sharpened that picture into what some researchers describe as a potential biosignature. One group, led by scientists at the University of Cambridge, argued that the spectral data are best explained by a Hycean world with abundant methane and relatively little ammonia, conditions they say could be compatible with life-supporting environments in a thick atmosphere above a liquid ocean. That interpretation, echoed in detailed discussions of K2-18 b, is what turned a routine exoplanet observation into a global headline about possible life signals.

A Hycean world in the habitable zone

To understand why K2-18b is such a compelling target, it helps to look at its basic properties. The planet orbits a cool red dwarf star in its habitable zone, the region where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist on a planetary surface. Classified as a sub-Neptune, it is larger than Earth but smaller than the ice giants in our own system, and models suggest it may host a deep global ocean capped by a thick hydrogen envelope. That combination is what defines a Hycean world, a category that has emerged as a promising new class of potentially life-friendly planets that are easier for telescopes like Webb to probe than small, rocky Earth analogues.

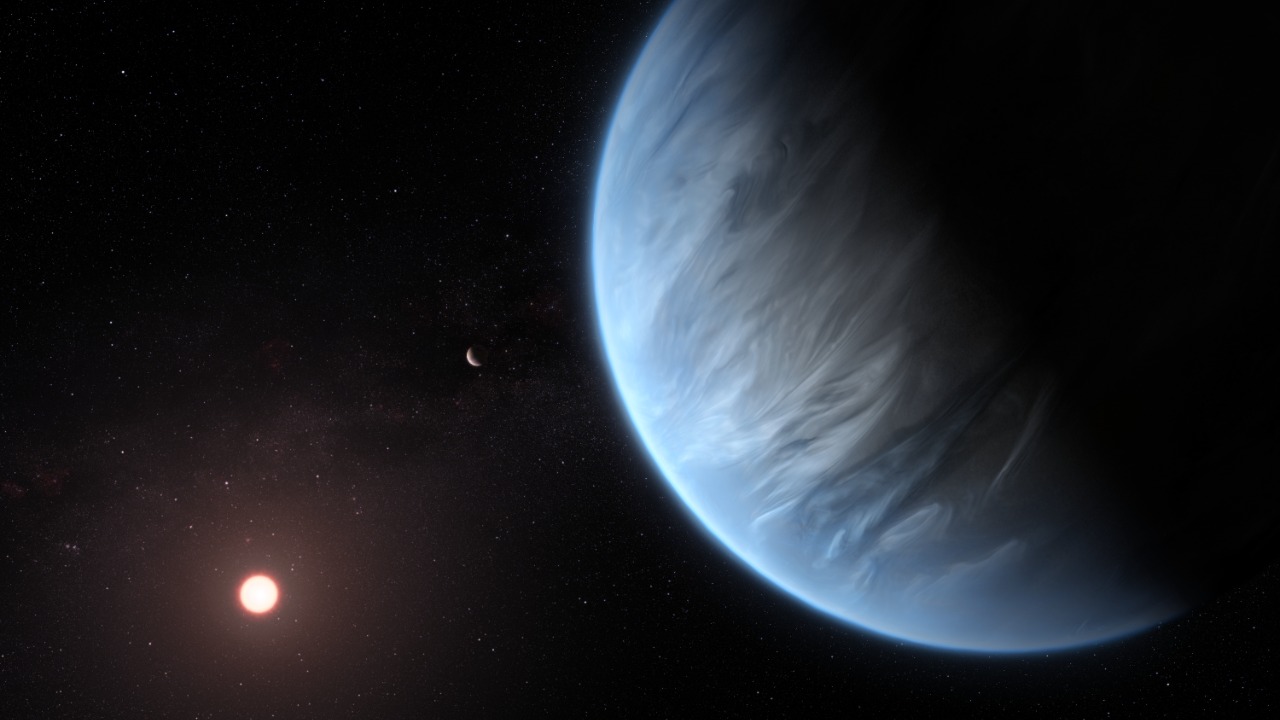

Reports on K2-18b emphasize that a Hycean planet with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere can still maintain temperate conditions at the ocean surface, even if the upper layers of the atmosphere are relatively hot. Illustrations of these Other worlds show a dim red sun hanging over a vast ocean, a scene that is speculative but grounded in the physics of how such atmospheres trap heat and circulate energy. K2-18b’s location at roughly 124 light-years away, highlighted in analyses that describe it as Scientists Find Promising, also makes it relatively nearby in galactic terms, close enough for Webb to collect multiple high-quality spectra over time.

The dimethyl sulfide claim and its critics

The most controversial part of the K2-18b story is the reported detection of dimethyl sulfide, or DMS. On Earth, this molecule is produced almost entirely by biological processes, particularly by marine phytoplankton, which is why some astronomers have treated it as a potential smoking gun for life. A team led by Nikku Madhusudhan at Cambridge University, described in coverage of On April findings, argued that Webb’s spectra contain a weak but consistent signal that could be explained by DMS alongside methane and carbon dioxide. In their view, if that interpretation holds, it would represent the most promising sign yet of a biosignature on an exoplanet.

Yet even within that team, caution has been the watchword. Nikku Madhusudhan, identified as the lead author of both Cambridge studies, has stressed that no actual life has been detected on K2-18b and that the DMS signal is at the edge of Webb’s current capabilities. He has compared the situation to seeing a faint shape in the fog that might be a person but could just as easily be a trick of the light, a point underscored in analyses that quote Nikku Madhusudhan directly. Other astronomers have gone further, arguing that the current data are too noisy to support any firm claim of DMS and that alternative explanations, including overlapping signals from more mundane gases, remain entirely plausible.

Reanalysis, doubt, and the scientific whiplash

As often happens with bold scientific claims, the initial excitement around K2-18b has been followed by a wave of scrutiny. Independent teams have reprocessed the same Webb data using different statistical methods and atmospheric models, and some of those efforts have cast doubt on the strength of the supposed biosignatures. One NASA-led project, described as a New study revisiting the signals, concluded that the evidence for DMS is inconclusive and that even the methane and carbon dioxide abundances are less tightly constrained than first advertised. In that view, the data are consistent with a range of atmospheric compositions, some of which would be far less hospitable to life.

Other researchers have focused on the technical details of how Webb’s instruments handle noise and systematics. A detailed New analysis emphasized that Astronomers have been poring over the spectra to determine whether the apparent features could arise from subtle calibration issues rather than real gas molecules of any kind. Jake Taylor, an astrophysicist at the University of Oxford, took another look at the Webb telescope data and came away unconvinced that the DMS signal is robust, arguing that the feature so integral in the Cambridge study’s findings may simply not survive more conservative processing, a point highlighted in coverage of Jake Taylor and his critique.

Why K2-18b still matters, even if it is a false alarm

Even if the dimethyl sulfide claim ultimately evaporates, K2-18b has already reshaped how astronomers think about the search for life. The planet has become a test case for how to interpret ambiguous signals from distant atmospheres, and for how to communicate those findings to a public eager for definitive answers. Commentaries that ask What has been found emphasize that using the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, the Cambridge team reported hints of molecules that on Earth are linked to organisms such as marine phytoplankton, but that such associations cannot simply be transplanted to an alien world without exhaustive checks for non-biological sources. That tension between excitement and restraint is, in my view, a sign of a healthy scientific process rather than a failure.

The broader context also matters. By early 2025, the James Webb Space Telescope had already built up a substantial track record on exoplanets, with dashboards tallying dozens of worlds studied in detail and more in the queue, as summarized in overviews of James Webb Space exoplanet science. K2-18b is just one target among many, but it illustrates how quickly the field is moving from simple detections of water vapor to nuanced debates over potential biosignatures. Whether or not life is ultimately confirmed there, the methods refined on this planet will shape how astronomers interpret future candidates, from other Hycean worlds to smaller, more Earth-like planets that Webb and its successors will scrutinize in the years ahead.

The public imagination and the road ahead

Part of what makes K2-18b so captivating is how neatly it maps onto familiar ideas of an ocean world teeming with microscopic life. Popular explainers have leaned into that imagery, describing how microorganisms akin to Earth’s phytoplankton could, in principle, inhabit a deep sea under a hydrogen sky, a scenario explored in pieces that ask Could life thrive on K2-18b and What a potential biosignature might look like. At the same time, more technical discussions have warned that the planet’s high gravity, thick atmosphere, and possible lack of a solid surface could make it a very alien environment, one where Earth-based intuitions about habitability may not apply.

Looking ahead, I expect K2-18b to remain a priority target for follow-up observations, both with Webb and with future missions. Plans already call for additional transits to be observed at different wavelengths, which should help clarify whether the contested spectral features persist and whether the atmosphere shows signs of clouds, hazes, or other complicating factors. The broader exoplanet community is also watching closely, as highlighted in pieces that describe possible signs of alien life on nearby exoplanets, the role of James Webb in spotting the first potential signs of life outside the Solar System, and the way JWST has already delivered tantalising hints on this particular world. Critical voices, including those summarized in Here and in discussions of Recently reexamined data, will continue to probe whether the signals are real or simply artifacts. Even informal conversations, such as those in online groups where users debate whether a potential biosignature is still present and note that Classified details of the target include its distance of 124, show how deeply this single planet has entered the public imagination. For now, K2-18b sits at the frontier of what Webb can reveal, a reminder that the first hints of life beyond Earth are likely to arrive not as a triumphant declaration, but as a careful, contested signal that demands patience, skepticism, and a willingness to be surprised.

More from Morning Overview