Signals from a distant world have pushed the search for alien life out of science fiction and into the realm of testable claims. Using the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers studying the exoplanet K2-18b have reported chemical fingerprints in its atmosphere that could, in the most optimistic reading, hint at biology. The evidence is far from settled, but the debate around those measurements is already reshaping how I think about what a “life signal” really looks like.

K2-18b orbits a faint red star more than a hundred light years away, yet its atmosphere is now one of the most scrutinized places in the cosmos. As researchers argue over whether Webb has glimpsed genuine biosignatures or a mirage created by noisy data and complex models, the planet has become a test case for how we will interpret the next generation of discoveries.

Why K2-18b jumped to the front of the life hunt

The basic facts about K2-18b explain why it vaulted to the top of astronomers’ target lists. It is a super sized cousin of Earth, nearly nine times our planet’s mass, and it circles its star at a distance where temperatures could allow liquid water. NASA notes that K2-18 b sits about 124 light years away, close enough for Webb to tease out the starlight that filters through its atmosphere during each transit. That combination of size, distance and orbital position makes it one of the few known worlds where we can realistically probe for gases linked to life.

Earlier observations already hinted that K2-18b might be wrapped in a thick hydrogen envelope above a deep global ocean, a configuration some researchers classify as a “Hycean” world. Reporting on whether life could thrive there has emphasized that the planet lies in the habitable zone of its star and might host microorganisms akin to Earth’s phytoplankton in a dim, watery environment, a possibility highlighted in an Apr explainer that asked whether alien life on K2-18b might resemble marine microbes. Those basic parameters set the stage for Webb’s more detailed look.

What Webb actually saw in K2-18b’s skies

The excitement around K2-18b comes from a specific pattern in its atmospheric spectrum, not from any direct image of alien oceans or continents. When the planet passes in front of its star, the James Webb Space Telescope measures how different wavelengths of starlight are absorbed, building up a chemical fingerprint of the gases overhead. In those data, researchers reported signs of carbon bearing molecules that are difficult to explain with simple, lifeless chemistry, a claim that quickly circulated as Webb’s strongest hint of biology so far and was dramatized in a video that described how Two years of observations with the James Webb Space Telescop built to this moment.

One of the most talked about features is a possible detection of dimethyl sulfide, a molecule that on Earth is produced almost entirely by living organisms in the oceans. A separate video summary framed this as a potential scientific breakthrough, noting that researchers using the James Webb Space Telescope had identified dimethyl sulfide in the atmosphere of K2-18 b, located 124 light years away in the direction of Leo. The same analyses also point to methane and carbon dioxide, a combination that, in some models, suggests an ocean covered world with active chemistry at the surface.

The Hycean world idea and why it matters

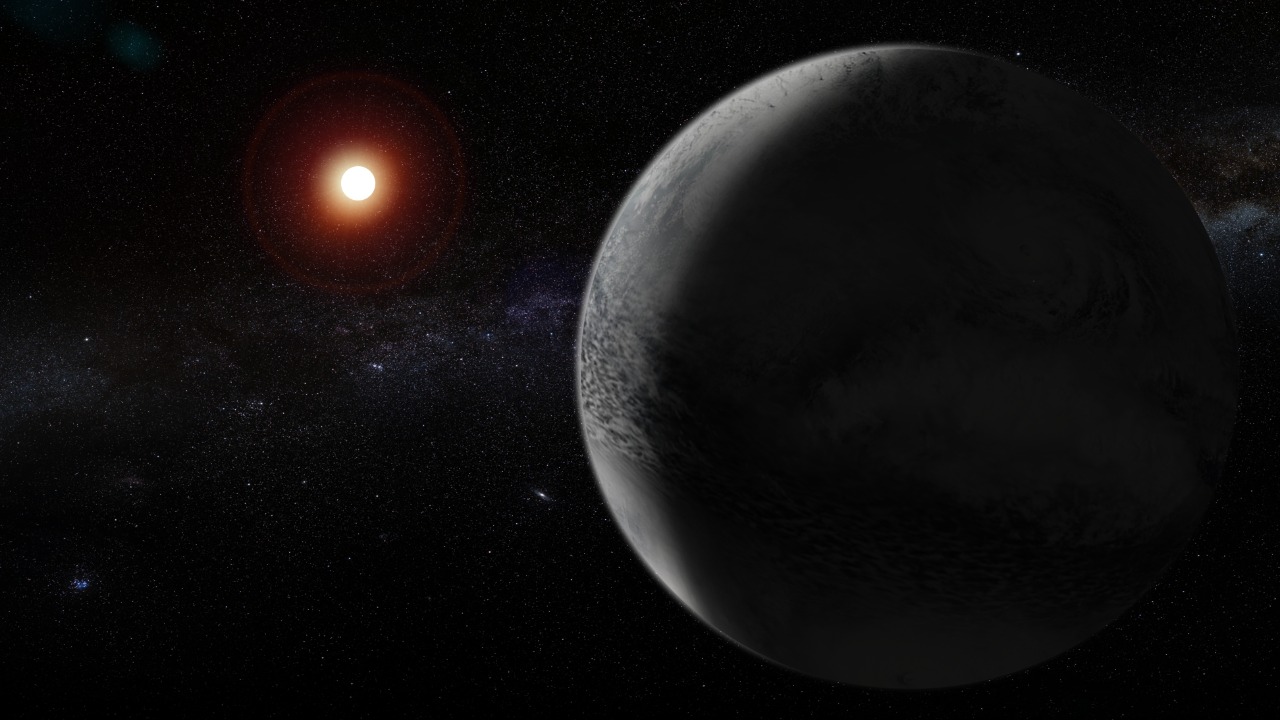

To understand why those gases caused such a stir, I have to look at the Hycean world concept that has grown around K2-18b. In this picture, the planet is neither a scaled up Earth nor a mini Neptune, but something in between, with a deep liquid water ocean hidden beneath a hydrogen rich atmosphere. An illustration of such a Hycean world, orbiting a red dwarf star and potentially hosting a liquid water ocean beneath a hydrogen rich sky, has been used to explain why K2-18b’s combination of size and temperature is so intriguing, as described in a feature on Other worlds that examined how Webb’s spectra might represent signs of biological activity.

Some researchers argue that a Hycean planet could be even more hospitable to life than Earth, because a global ocean and thick atmosphere might stabilize climate over billions of years. Others are more cautious, pointing out that a hydrogen dominated sky would create high pressures and potentially harsh conditions at the ocean surface. In one analysis of Webb’s K2-18b data, scientists noted that Some propose a Hycean world as the best fit for the observations, but also warned that enthusiasm is outpacing evidence, a tension captured in a report that contrasted the new Webb spectra with earlier Hubble Telescope views that had obscured key details.

From “strongest evidence yet” to sharp skepticism

Once the first Webb based claims landed, the rhetoric escalated quickly. A team at Cambridge University argued that the combination of gases in K2-18b’s atmosphere represented the strongest evidence yet of life beyond Earth, focusing on the potential dimethyl sulfide signal and the planet’s position in its star’s habitable zone. Coverage of their work emphasized that Cambridge University scientists were pointing to a world 124 light years away and that the planet is called K2-18b, framing the result as a landmark in the search for extraterrestrial biology.

At the same time, other astronomers were already urging caution. A detailed explainer asked whether Webb had really found evidence of alien life and stressed that the data are compatible with multiple atmospheric models, some of which do not require biology at all. That piece noted that in a University of Cambridge led study, the team itself acknowledged that the detection of dimethyl sulfide is tentative and that the observations fall short of a definitive proof of life, a nuance highlighted in an analysis that asked Did the James Webb really find evidence of alien organisms and promised to explain Here is the truth about exoplanet K2-18b.

How reanalysis turned “biosignatures” into a live controversy

The most serious pushback has come from teams that revisited the same Webb data with different assumptions and statistical tools. In one New analysis, Astronomers reprocessed the spectra and argued that the supposed biosignatures might be artifacts of the way the original team modeled the planet’s atmosphere and instrument noise. Their work cast doubt on whether dimethyl sulfide is present at all and suggested that simpler mixtures of methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen could fit the data just as well, a conclusion laid out in a report that described how Astronomers used careful analysis to test whether the claimed biosignatures might be a lot of hot air.

Another study, led by NASA researchers, revisited the same Webb observations and reached a similarly cautious conclusion. That work found inconclusive evidence for a tantalizing life signal, arguing that the current data do not allow scientists to distinguish between biological and non biological explanations with high confidence. The authors stressed that astronomers have long sought signs of life in exoplanet atmospheres, but that K2-18b’s case illustrates the challenges of interpreting such signals, a point underscored in a New summary of the NASA led reanalysis.

Why Webb’s power is both a gift and a headache

Part of the confusion stems from just how powerful Webb is. When the observatory, often shortened to JWST, began sending back data, Scientists were in awe of the flood of information and the unprecedented precision of its measurements. That deluge has allowed researchers to probe exoplanet atmospheres in exquisite detail, but it has also forced them to confront subtle instrument systematics and modeling degeneracies that were irrelevant with older telescopes, a dynamic described in a reflection on how the James Webb Space Telescope “broke” the universe by overwhelming researchers with data.

The same tension appears in other areas of cosmology, where Webb’s precision has sharpened, not resolved, long standing debates. Work on the Hubble constant, for example, has used JWST measurement campaigns to hint at a value near 70 kilometers per second per megaparsec, yet, as of 2025, scientists remain divided, with measurements yielding conflicting results that challenge the foundations of our understanding of the cosmos. That broader context, summarized in a discussion that opened with the word Yet to emphasize the ongoing disagreement, shows how even the best data can deepen uncertainty, a lesson that clearly applies to the K2-18b life debate and is captured in an overview of measurement tensions.

How scientists try to avoid another “false alarm”

Given that history, it is no surprise that many researchers are treating K2-18b as a stress test for how to claim a biosignature responsibly. One detailed breakdown of the Webb observations framed the dimethyl sulfide hint as a possible signal, not a discovery, and walked through how the team compared different atmospheric models to see which best matched the data. The authors emphasized that signals from K2-18 b must be checked against alternative explanations and that the community is working to avoid this kind of mistake by demanding multiple, independent lines of evidence before declaring life, a standard laid out in an Apr analysis of the possible sign of life.

Others have gone further, arguing that we should expect some false alarms as Webb and future telescopes push into new territory. A critical commentary on the K2-18b claims noted that Still, many scientists are once again injecting doses of skepticism into the high profile announcement, stressing that the sought after molecule in K2-18b’s atmosphere sits at the edge of detectability. That piece argued that the community needs to normalize the idea that some of these early “life” signals will not hold up, a perspective captured in a discussion that asked whether we actually found signs of alien life on K2-18b and warned that this may be one of the false positives, a warning anchored in the word Still.

What counts as a “signature of life” anyway?

Underneath the back and forth over dimethyl sulfide is a deeper question about what a life signal actually looks like. NASA’s own guidance on the search for biosignatures stresses that scientists will likely need to see combinations of gases that are hard to maintain without biology, such as mixtures of oxygen, carbon dioxide and methane that are out of chemical equilibrium. The agency’s overview of how we might find life beyond our planet explains that we will have to decide whether we will know life when we see it by looking for atmospheric patterns that cannot be explained by geology or photochemistry alone, a framework laid out in its Can We Find Life? roadmap.

In that context, K2-18b is both promising and frustrating. The reported mix of methane, carbon dioxide and possible dimethyl sulfide is unusual, but researchers are still debating whether non biological processes in a Hycean environment could generate similar spectra. A newsletter style deep dive into the K2-18b observations noted that using the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have detected chemical fingerprints that could belong to a signature of life on a distant planet, but also stressed that the same data might be consistent with exotic but lifeless chemistry, a nuance captured in a feature that described how Hycean worlds could produce signals representing signs of biological activity without guaranteeing it.

Why K2-18b still matters, even if life is not confirmed

Regardless of how the dimethyl sulfide debate is resolved, K2-18b has already changed the conversation about exoplanets. It has shown that Webb can not only detect atmospheres on distant worlds but also pick out subtle combinations of gases that invite biological interpretations. A roundup of the most exciting exoplanet discoveries of 2025 highlighted the search for life on K2-18b, noting that an illustration of a blue planet with a bright star in the background had become an emblem of how quickly hints of possible life can ignite scientific debate, a dynamic captured in a feature that described how the search for life on K2-18b swiftly ignited controversy.

The planet has also become a touchstone for public fascination with alien oceans and for more grounded discussions about how to interpret ambiguous data. A widely shared explainer asked whether life could thrive on K2-18b and walked through what we know about its mass, orbit and potential for microorganisms akin to Earth’s phytoplankton, while also reminding readers that the evidence remains circumstantial, a balance struck in an Apr piece that framed the question as Could life thrive on K2-18b? What to know about the distant exoplanet. Even if the current signals turn out to be noise, the methods honed on this world will shape how we read the atmospheres of the next generation of potentially habitable planets.

More from MorningOverview