Fusion power has long been treated as a mirage on the energy horizon, but the construction cranes outside Boston suggest something more concrete is taking shape. Commonwealth Fusion Systems is racing to finish its SPARC pilot plant and a first commercial site in Virginia, betting that a mix of high-temperature superconducting magnets and artificial intelligence can turn fusion from physics experiment into grid resource within the next decade. I see a technology that has inched forward for generations suddenly colliding with industrial-scale capital, digital tools and geopolitical urgency.

From lab dream to construction site outside Boston

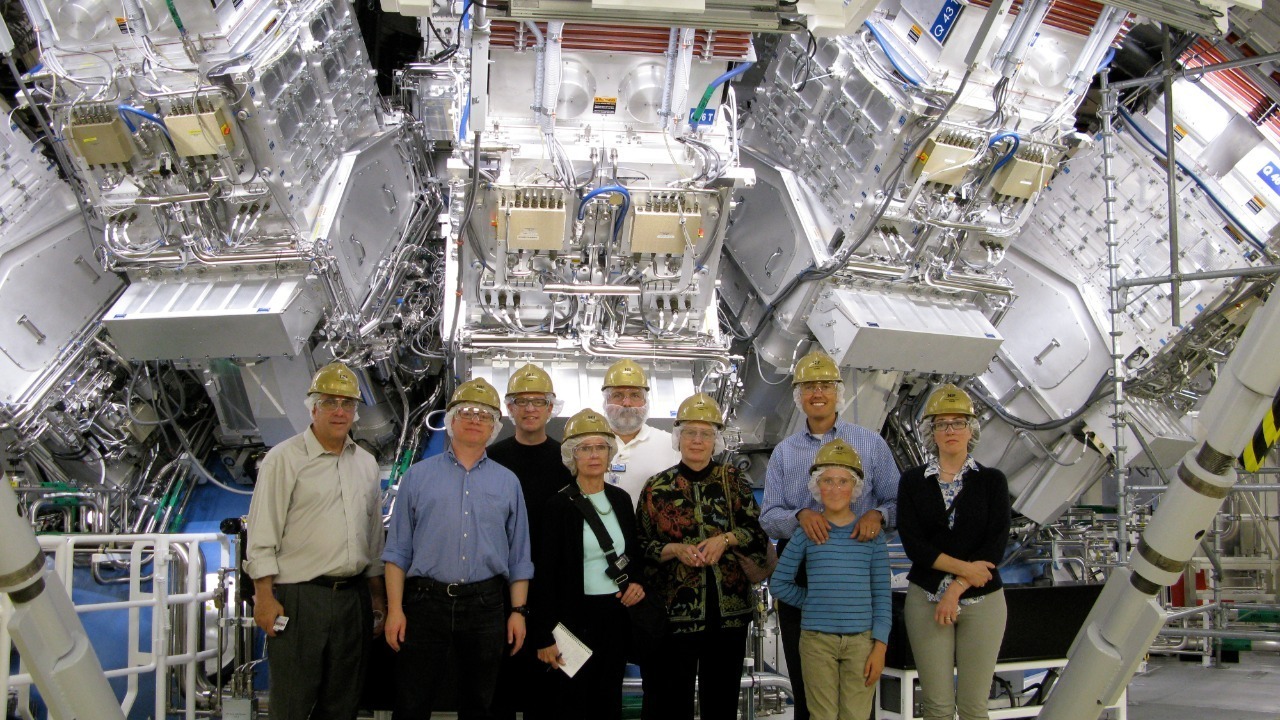

For most of its history, fusion has lived in national laboratories and on whiteboards, not in places where neighbors worry about traffic and construction noise. That is changing as CFS, often shortened from Commonwealth Fusion Systems, pushes ahead with its SPARC demonstration project on an industrial campus outside Boston. The company has already installed the first of 18 high-temperature superconducting magnets that will form the heart of the compact tokamak, a milestone that turns a decade of design work into visible hardware and signals that the pilot plant is no longer a paper reactor but a machine under assembly, as described in detailed coverage of how CFS is currently building its SPARC demonstration project outside of Boston.

The stakes around that construction site are unusually high for a single experimental facility. SPARC is designed to show that a relatively small device, powered by those high-field magnets, can achieve the conditions needed for net fusion energy by melding hydrogen isotopes together, rather than relying on sprawling, decades-long megaprojects. If the machine performs as planned, it will not just validate a magnet technology, it will validate a business model that assumes fusion plants can be built on timelines and budgets closer to conventional power stations than to space telescopes, a premise that underpins the broader claim that fusion power is nearly ready for prime time.

SPARC’s technical leap and the 2027 first-plasma clock

SPARC is not intended to be a commercial generator, but it is engineered to answer the most important technical question in fusion: can a compact, magnetically confined plasma produce more energy than it consumes. The design leans on high-temperature superconductors that allow much stronger magnetic fields in a smaller volume, which in turn should make it easier to confine the superheated plasma where fusion reactions occur. CFS has framed SPARC as a bridge between decades of plasma physics and the first generation of grid-scale plants, positioning the device as the proof point that commercial fusion energy is possible, a role spelled out in the company’s description of how SPARC is paving the way for the urgent transition to clean, safe, zero-carbon fusion energy.

The timeline attached to that proof is aggressive by fusion standards. CFS has said it is targeting first plasma energy in 2027, effectively giving itself only a few years from the first magnet installation to a fully integrated, operating machine. That schedule compresses what used to be generational milestones into a single planning cycle for utilities and regulators, and it is central to the argument that fusion is moving from aspirational to actionable. Reporting on the project notes that the company expects first plasma energy in 2027, a date that now functions as a countdown clock for the entire fusion sector.

Virginia’s ARC plant and the promise of grid power

While SPARC takes shape in Massachusetts, CFS is already mapping out the next step: a full-scale power plant in Chesterfield County, Virginia. The company has committed that it will bring clean fusion energy to the grid from its campus in Chesterfield County, Virginia, turning a former fossil-heavy region into a showcase for advanced nuclear technology. In its own materials, CFS describes how our first power plant in Chest will be ARC in the early 2030s, a phrasing that underscores both the local branding and the company’s confidence that SPARC’s physics will translate into a commercial design.

The Virginia project is more than a siting decision, it is a signal that fusion developers are starting to think like utilities and industrial planners rather than just experimentalists. By committing to Chesterfield County, CFS is tying its fortunes to a specific community, workforce and grid, inviting scrutiny over jobs, safety and long-term economic impact. The ARC plant is pitched as the world’s first grid-scale fusion power station, and if it hits its early 2030s target, it would move fusion from the realm of demonstration to the realm of capacity planning, where gigawatts and reliability metrics matter as much as scientific breakthroughs.

Digital twins, Siemens Xcelerator and Nvidia’s AI muscle

One reason CFS can talk about overlapping timelines for SPARC and ARC is that it is leaning heavily on digital tools to shorten the traditional build-test-redesign cycle. The company has announced that it will use the Siemens Xcelerator portfolio to create a detailed digital twin of its fusion systems, feeding in data from design, manufacturing and operations so engineers can iterate virtually before committing to hardware. In its own description of the partnership, CFS explains that as part of this initiative, CFS will use the Siemens Xcelerator portfolio with layering of AI-enabled tools, a strategy that mirrors how aerospace and automotive firms now design complex machines. Those AI-enabled tools are not abstract buzzwords, they are tied to specific hardware and software stacks from Nvidia and Siemens that can run high-fidelity simulations of plasma behavior, magnet performance and plant operations. A separate account of the collaboration notes that Commonwealth Fusion Systems is launching a digital twin with Nvidia and Siemens so it can run simulations and test hypotheses in virtual space before making changes in the real world. The idea is that by building a rich model where Commonwealth Fusion Systems launches digital twin with Nvidia and Siemens to run simulations and test hypotheses, the company can compress years of experimental tweaking into months of computational work, a critical advantage when every delay pushes commercial fusion further into the future.

Magnets, “bang, bang, bang” assembly and Nvidia’s Omniverse

The installation of SPARC’s first magnet is not just a construction milestone, it is the start of a rapid-fire assembly sequence that CFS executives have described in vivid terms. One leader said that “it’ll go bang, bang, bang throughout the first half of this year as we put together this revolutionary technology,” capturing both the pace and the confidence behind the build. That same description links the physical assembly to a broader digital strategy, noting that the company plans to integrate its design and operational data into Nvidia’s Omniverse libraries so that the virtual and real machines evolve together, a plan highlighted in reporting on how “It’ll go bang, bang, bang” as CFS installs magnets and feeds it into Nvidia’s Omniverse libraries.

The magnet work is also central to a separate account that focuses on the company’s deal with Nvidia. That report notes that Commonwealth Fusion Systems installs reactor magnet, lands deal with Nvidia, and it credits reporter Tim De Chant with detailing how AI tools will be woven into the engineering workflow. The piece even includes a specific metric, 202, that appears in the context of the company’s broader funding and staffing picture, underscoring how quickly the fusion startup has scaled from a handful of researchers to an industrial operation. By tying the physical milestone of the first magnet to a narrative where Commonwealth Fusion Systems installs reactor magnet, lands deal with Nvidia, as Tim De Chant reports from PST, CFS is signaling that its magnets are not just components, they are proof that a new fusion-industrial complex is taking shape.

CES spotlight and the race for AI-powered fusion

Fusion rarely used to feature at consumer tech shows, but that changed when CFS shared the stage with Nvidia and Siemens at CES. In a segment that otherwise focused on gadgets and digital services, the companies highlighted how AI and industrial software could accelerate fusion energy research, turning what used to be decade-long experimental campaigns into rapid, data-driven cycles. Coverage of the event noted that Fusion energy research gets a little support from Nvidia, Siemens, Commonwealth Fusion Systems, a modest phrase that understates the significance of putting fusion on the same stage as mainstream AI announcements.

The CES spotlight also intersected with a broader narrative about how major tech firms are positioning themselves in the energy transition. Another account of the show described how a CEO named Yang Yuanqing shared the stage with Nvidia’s Huang and AMD CEO Lisa Su to promote longevity and advanced computing, and within that context, fusion was framed as one of the ultimate long-term bets for clean power. The same report emphasized that Fusion energy research gets a little support from Nvidia, Siemens, turning years of experimentation into weeks of understanding, a line that captures both the ambition and the marketing pitch behind the AI-fusion nexus.

Global competition, US fusion strategy and China’s moves

As CFS accelerates its pilot plant, it is doing so against a backdrop of geopolitical competition that is starting to shape fusion policy. A recent digest of industry developments, framed as Things You Gotta Know, warned that the US Fusion Strategy Stuck in the Past as China Moves Ahead, quoting a CEO who argued that American efforts risk being outpaced by more coordinated state-backed programs. That same newsletter, published under the banner of This Week’s Fusion News: January 2, 2026, which lists Things You Gotta Know and highlights Fusion Strategy Stuck in the Past as China Moves Ahead, CEO warns, situates CFS’s progress within a larger race where regulatory clarity, public funding and supply chains could determine which country hosts the first wave of commercial fusion plants.

Internationally, the fusion landscape is already crowded, from the long-running ITER project to national programs in Europe and Asia, but the emergence of private firms like CFS adds a new dimension. The World Economic Forum has argued that Commonwealth Fusion Systems will turn fusion from a scientific experiment into a commercial reality, suggesting that its first successful plant could be fusion’s Wright Brothers moment. In that framing, described in an analysis that notes how Commonwealth Fusion Systems will turn fusion from experiment to industry and could be fusion’s Wright Brothers moment, the question is not just whether the physics works, but whether the United States can align its industrial and regulatory policies quickly enough to keep pace with rivals like China that are moving aggressively into advanced nuclear and clean energy manufacturing.

From net gain at Lawrence Livermore to SPARC’s commercial pivot

The sense that fusion is finally within reach did not start with CFS, it was catalyzed when Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California achieved what physicists call Lawson’s criterion, producing the first net energy gain from a controlled fusion experiment. That inertial confinement result, achieved with powerful lasers, proved that fusion reactions can, under the right conditions, yield more energy than they consume, even if the setup is not directly translatable to a power plant. The milestone is often cited as a turning point, and it is explicitly referenced in accounts that recall how then, in 2022, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California achieved Lawson’s criterion, giving private fusion companies a powerful proof-of-concept to point to when courting investors and policymakers.

SPARC represents a different path to the same goal, using magnetic confinement rather than lasers, but it is clearly part of the same narrative arc. Where Lawrence Livermore’s experiment was a national lab triumph, SPARC is a private-sector bet that the physics is mature enough to justify commercial timelines and capital structures. If SPARC can demonstrate sustained net energy gain in a compact tokamak, it will validate not just CFS’s design choices but the broader thesis that fusion can be industrialized quickly, turning what was once a purely scientific quest into a race to build plants like ARC in Chesterfield County, Virginia, and beyond.

Virginia as fusion epicenter and the Ark narrative

The choice of Virginia for CFS’s first commercial plant is already reshaping how state and local leaders talk about their economic future. In a public announcement, company representatives said that they just announced that they will build our first power plant Ark in Chesterfield County Virginia, and they framed the project as the epicenter for fusion power and an innovation hub for fusion for the world. That language, captured in a video where we just announced that we will build our first power plant Ark in Chesterfield County Virginia, reflects a deliberate attempt to brand the region not just as a host site but as a global center for a new industry.

A separate video message reinforced that positioning, with CFS leaders promising that Virginia will be the epicenter for fusion power and that the state will be an innovation hub for fusion for the world. In that clip, they emphasize that the first fusion power plant in Virginia will anchor a broader ecosystem of research, manufacturing and training, effectively turning Chesterfield County into a campus for next-generation energy. The message, preserved in a recording where Commonwealth Fusion Systems to build world’s first fusion power plant Virginia will be the epicenter for fusion power, shows how the company is weaving local pride, national energy security and global climate goals into a single narrative around its pilot plant.

Limitless power, 300,000 homes and the grid-scale stakes

Behind the technical jargon and regional branding lies a simple promise: abundant, zero-carbon electricity. CFS has suggested that a single commercial-scale fusion plant based on its technology could generate enough power for about 300,000 homes, a figure that helps translate plasma physics into kitchen-table terms. That estimate appears in discussions of how CFS is currently building its SPARC project to power about 300,000 homes, and it underscores why utilities and grid operators are starting to pay attention: if even a fraction of those projections hold, fusion could become a meaningful contributor to baseload power in regions that now rely heavily on gas and coal.

The rhetoric around “nearly limitless clean power” is not just marketing, it reflects the underlying physics of fusion, which uses small amounts of fuel to release large amounts of energy with minimal long-lived waste. At CES, one description of the CFS presentation noted that a US energy company installs first fusion magnet, nears clean power breakthrough, and that the firm is partnering with Nvid to build a digital twin of Sparc. That account, which highlights how a US energy company installs first fusion magnet, nears clean power breakthrough with a digital twin of Sparc producing nearly limitless clean power, ties the aspirational language directly to specific engineering steps, reinforcing the idea that the path from magnet installation to megawatts is no longer purely hypothetical.

Energy security, foreign supply chains and political stakes

Fusion’s appeal is not limited to climate math, it is increasingly framed as a tool for energy security and industrial independence. Advocates argue that a domestic fusion industry could reduce dependence on foreign supply chains for critical fuels and technologies, insulating countries from geopolitical shocks and commodity price swings. That argument is explicit in a recent analysis that describes how Fusion power nearly ready for prime time as Commonwealth builds first pilot for limitless, clean energy with AI help from Fusion and reduces dependence on foreign supply chains, linking CFS’s pilot directly to broader national goals.Those political stakes are already influencing how leaders talk about fusion in the context of industrial policy and climate commitments. With President Donald Trump back in the White House, debates over federal support for advanced nuclear and clean energy technologies are likely to intensify, and companies like CFS will find themselves navigating a complex mix of enthusiasm for domestic manufacturing and skepticism toward long-term subsidies. In that environment, the ability to point to concrete milestones, from SPARC’s magnets outside Boston to the planned ARC plant in Chesterfield County, Virginia, may prove as important as any scientific paper in convincing policymakers that fusion is not just a moonshot, but a near-term asset in the country’s energy portfolio.

More from Morning Overview