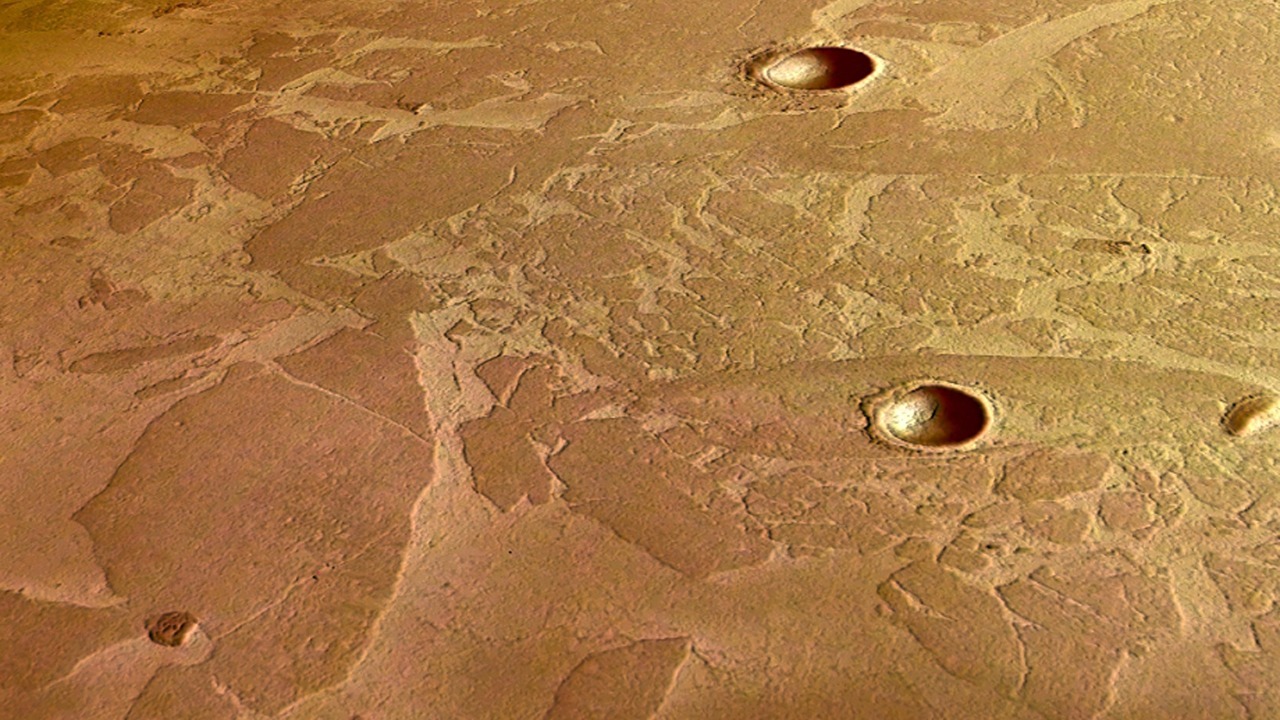

Hints of buried water on Mars have swung between tantalizing and controversial, but one idea keeps resurfacing: lakes could persist if they sit beneath a protective lid of ice. Instead of needing a warm, thick atmosphere, pockets of brine might survive in the cold if they are sealed off from the harsh surface and insulated just enough to avoid freezing solid. I see that possibility reshaping how scientists think about Martian habitability, especially in the planet’s polar regions.

Why a thin ice lid matters for Martian lakes

The phrase “thin ice lid” sounds fragile, but in planetary terms it describes a powerful shield. A relatively modest cap of ice can block direct contact with the frigid Martian air, trap geothermal heat rising from below, and keep any underlying water from evaporating into the thin atmosphere. On Earth, subglacial lakes in Antarctica rely on a similar balance of pressure, insulation, and internal heat, and researchers are now applying that logic to Martian polar terrains where surface conditions are far more extreme.

On Mars, the stakes are higher because most surface water is believed to have vanished long ago. It is widely accepted that a large fraction of Martian water escaped to space along with much of the atmosphere, while the rest became locked into polar caps and subsurface deposits. In that context, any configuration that lets liquid persist, even as salty brine under ice only a few kilometers across, becomes central to the search for habitable niches. A thin lid is not a guarantee of a lake, but it is one of the few physically plausible ways liquid water could still exist there today.

From radar bright spots to a polar lake controversy

The modern debate over Martian lakes ignited when radar reflections from the south polar region were interpreted as evidence of a buried body of liquid water. The signal, detected beneath the layered ice deposits, looked unusually bright and smooth, which some researchers argued was consistent with a subglacial lake similar to those under Antarctic ice. That interpretation suggested a stable reservoir of briny water, potentially kilometers wide, trapped beneath a protective ice cover and warmed slightly by the planet’s interior.

Follow up work, however, has steadily chipped away at the certainty of that claim. New radar analyses and modeling have pointed out that the same bright reflections could arise from dry materials or complex layering within the ice itself, without requiring any liquid. In particular, new observations have argued that Mars south pole likely lacks a large lake beneath the ice, casting doubt on the original interpretation of those radar bright spots. The result is a scientific split: the radar data remain intriguing, but the simplest explanation may no longer be a vast hidden sea.

Clay minerals and the case against a giant south polar lake

Mineralogy has added another layer of skepticism to the idea of a huge liquid reservoir at the south pole. When scientists examined the region using orbital instruments sensitive to surface composition, they found signatures that look more like solid materials than open water. One key clue came from the detection of possible clay minerals in and below the south polar ice cap, which suggests long term chemical alteration rather than a present day, extensive lake.

Those clay signatures matter because they can mimic some of the radar properties that were initially attributed to liquid water. If clays or other hydrated minerals are present, they can produce strong reflections without requiring a briny pool. A study from York University highlighted that Detecting possible clay minerals in and below the south polar ice cap is important precisely because it offers an alternate explanation for the radar signal that does not rely on the presence of liquid water. In other words, the mineral context undercuts the most dramatic version of the lake hypothesis, even if it does not rule out smaller or more localized pockets of brine.

Ancient frozen lakes versus modern under-ice water

Even as the case for a single large south polar lake weakens, the broader picture of Martian water history still leaves room for both ancient and modern lakes. Geological evidence points to a time when Mars had rivers, deltas, and standing bodies of water on its surface, many of which later froze or sublimated away. Some models now suggest that remnants of those ancient lakes could survive as frozen deposits, while more recent processes might create smaller, modern lakes under glaciers or ice caps where conditions allow.

Conference work on liquid water lakes on Mars has emphasized that most Martian water is now hidden in polar hats and subsurface ice, with potential under-ice lakes only a few kilometers in diameter. These would not be vast oceans but rather isolated pockets, perhaps stabilized by salts such as perchlorate that lower the freezing point. In that scenario, a thin ice lid becomes the final ingredient that allows a small volume of brine to remain liquid, bridging the gap between Mars’s wetter past and its dry, cold present.

How salts and pressure help a thin lid keep water liquid

For a lake to survive under Martian ice, the physics and chemistry have to cooperate. The pressure from even a modest ice cover can slightly raise the melting point of water, while insulating it from the brutal temperature swings at the surface. At the same time, dissolved salts can dramatically depress the freezing point, allowing brines to stay liquid at temperatures where pure water would be solid. Together, these effects mean that a relatively thin lid, perhaps only tens or hundreds of meters thick, could be enough to maintain a subglacial pocket of brine.

Studies of potential perchlorate rich lakes highlight how important these salts are to the equation. Perchlorate brines can remain liquid at well below the freezing point of pure water, which makes them prime candidates for any surviving Martian lakes. If such a brine sits under an insulating ice lid, even the modest geothermal heat flow from the Martian interior could be enough to keep it from freezing completely. The result would not be a comfortable environment by Earth standards, but it would be a chemically and thermally stable niche in an otherwise hostile landscape.

Dusty ice, gullies, and hints of shallow subsurface water

Evidence for water related processes on Mars is not confined to the deep polar caps. In mid latitude regions, spacecraft have spotted gullies and deposits that look like they were carved or modified by flowing material, possibly involving melting ice. In 2021, a study by Oct, Christensen and Khuller reported dusty water ice exposed within gullies on the Martian surface, suggesting that shallow subsurface ice can be mobilized under the right conditions. That kind of activity hints at a dynamic interplay between ice, dust, and occasional melting, even in areas far from the poles.

More recent work has extended that line of thinking to the potential for life beneath the ice. A NASA study led by Oct, Christensen and Khuller explored whether microbial life could exist below Mars ice, using the discovery of dusty water ice in gullies as a starting point. The idea is that even thin layers of overlying material can create microenvironments where liquid films or transient brines form, protected from radiation and extreme cold. While these are not lakes in the classic sense, they reinforce the broader lesson that modest coverings of ice or regolith can dramatically change the habitability of Martian niches.

What Earth’s subglacial lakes teach me about Mars

When I think about thin ice lids on Mars, I inevitably compare them to Earth’s own hidden lakes. Under Antarctica’s ice sheet, bodies of water like Lake Vostok remain liquid thanks to a combination of pressure, geothermal heat, and insulating ice that can be several kilometers thick. The analogy is not perfect, since Mars is colder and drier, but the basic physics of subglacial hydrology still applies. If Earth can host thriving microbial ecosystems in such isolated, dark lakes, it is reasonable to ask whether Mars could do something similar on a smaller, saltier scale.

The radar techniques used to infer lakes on Mars were honed in part by mapping these terrestrial subglacial systems. When scientists first reported Liquid water found beneath the surface of Mars, they explicitly compared the radar reflections to those seen from lakes under Antarctica. The key difference is scale and certainty: on Earth, we can drill through the ice to confirm what the radar shows, while on Mars we are still interpreting signals from orbit. Even so, the Earth analogy strengthens the case that a thin lid of ice is not just a theoretical construct but a proven way for liquid water to survive in extreme environments.

Life beneath the lid: habitability under Martian ice

If thin ice lids can preserve pockets of liquid, the next question is whether those pockets could support life. From a biological perspective, subglacial lakes offer several advantages over the Martian surface. The ice shields any underlying water from intense ultraviolet radiation and cosmic rays, while also buffering temperature swings that would otherwise freeze and thaw any exposed liquid. Salty brines may be chemically challenging, but on Earth, microbes have adapted to hypersaline lakes and deep subsurface aquifers that are just as extreme.

The possibility of life below Mars ice hinges on whether there is enough energy and nutrient flow to sustain metabolism. Geochemical gradients at the interface between rock, ice, and brine could provide that energy, much as they do in Earth’s subsurface ecosystems. I find it telling that multiple lines of research, from dusty ice in gullies to potential under-ice brines at the poles, converge on the same theme: thin layers of overlying material can transform an otherwise sterile environment into one where microbial life is at least conceivable. The thin lid is not just a physical barrier, it is a potential gateway to habitability.

Why the lake debate still matters for future missions

Even if the original claim of a large south polar lake does not hold up, the debate has already reshaped how mission planners think about Mars. The possibility that small, briny lakes or wet zones exist under thin ice lids has pushed subsurface exploration higher on the agenda. Instead of focusing solely on ancient river deltas and dried up lakebeds, scientists are now weighing the value of drilling or melting through polar and mid latitude ice to sample what lies beneath. That shift reflects a broader recognition that present day habitability might be hiding in places that look inert from orbit.

Future landers and orbiters will have to navigate the tension between tantalizing radar hints and the sobering reinterpretations that followed. New instruments will need to distinguish more clearly between signals from clays, dry ice, and true liquid water, building on the lessons from Mars south pole studies and the mineral detections that followed. I expect that as those tools improve, the concept of a thin ice lid will remain central, not because it guarantees lakes, but because it captures the delicate balance of pressure, temperature, and chemistry that any surviving Martian water must obey.

More from Morning Overview