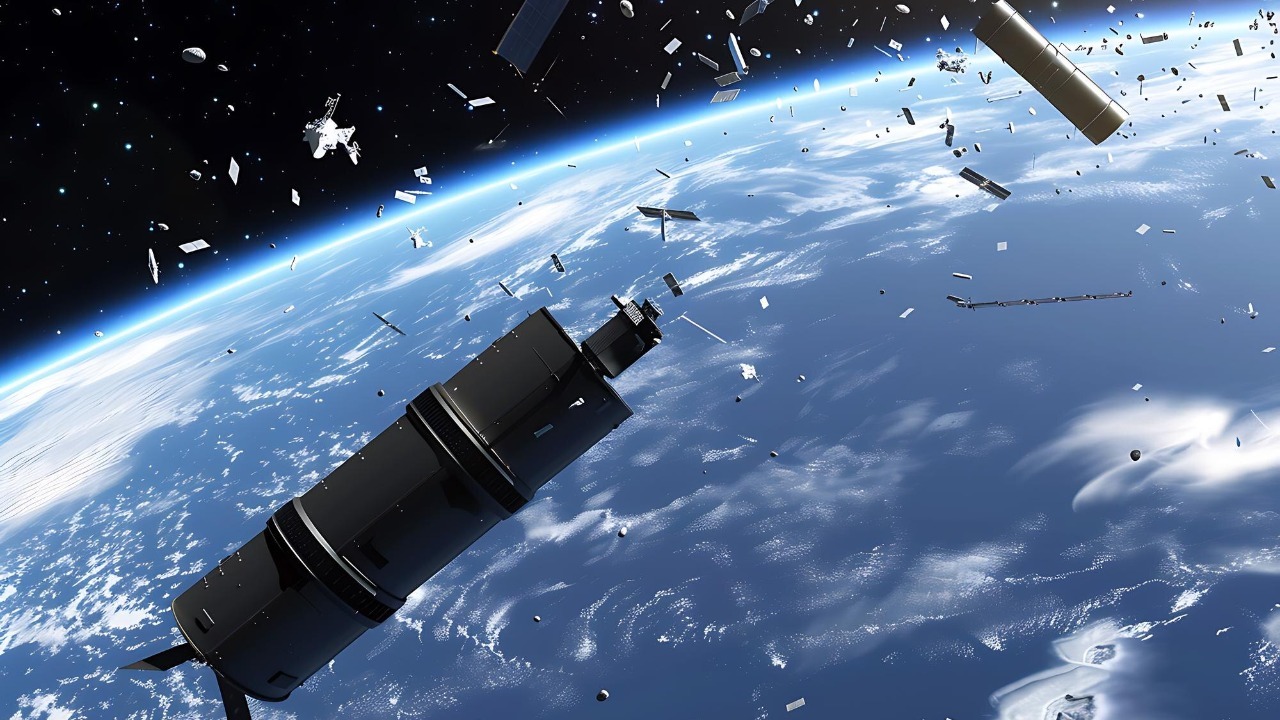

Falling hardware from orbit used to be the stuff of science fiction. Now, as launch rates surge and commercial aviation rebounds, researchers say the odds that a piece of space junk will cross paths with an airliner are no longer negligible. The overall risk to any single passenger remains low, but the chance that debris will pass through busy airspace and force pilots and controllers to react is rising fast.

Experts are warning that this is not just a curiosity of the space age but a concrete safety and disruption problem for airlines, regulators and launch companies. The same growth that is filling the skies with satellites and rockets is quietly loading more metal into the narrow band of atmosphere where modern jets cruise.

From remote hazard to real-world probability

For decades, the idea of a falling satellite hitting an aircraft was treated as a vanishingly small possibility, something that could be filed away with lightning strikes and freak turbulence. That framing is starting to shift as analysts quantify how often large objects now come down through the same altitudes that carry transcontinental and transoceanic traffic. One recent assessment put the chance that, within a single year, debris will fall through some of the world’s busiest air routes at 26% for a major fragment, a figure that reflects how crowded low Earth orbit has become.

Researchers who model these events stress that the odds of a direct hit on a specific aircraft are still small, but they also note that a collision between a commercial jet and a dense piece of hardware would be catastrophic. In work highlighted by Feb risk analyses, the same teams point out that the number of uncontrolled reentries is set to grow for decades, which means the cumulative probability of an encounter with aviation is no longer trivial.

Why the risk is “small but growing”

When I talk to aviation and space safety specialists, they tend to use the same phrase about this threat: small but growing. That captures the tension between individual and systemic risk. For any one passenger boarding a flight, the chance of being struck by debris is tiny, yet when you multiply that by tens of thousands of daily flights and a rising tempo of reentries, the odds that some aircraft somewhere will be affected start to look more serious. One breakdown framed it bluntly, noting that while the Answer, Small but growing, the probability that debris will pass through busy airspace is not small at all.

New modeling work backs that up by tying the risk directly to two curves that are both pointing upward: the number of objects falling back to Earth and the number of aircraft in the sky at any given moment. As one New research effort put it, the risk is rising because both reentries and airline flights are increasing, and uncontrolled space debris reentries are likely to remain a feature of the orbital environment for years to come.

How falling debris actually threatens aircraft

To understand why experts are worried, it helps to picture what happens when a rocket body or satellite reenters. As it slams into thicker air, it breaks apart, with most fragments burning up but some surviving down to altitudes where jets cruise. Those surviving pieces can be anything from small shards to multi-kilogram chunks of metal, and they do not fall straight down. Instead, they streak along the ground track of the original orbit, cutting diagonally across flight corridors that have been optimized for fuel efficiency, not for avoiding space hardware.

Analysts who study these trajectories have found that Large reentries occur almost weekly, and that “Over 2,300 rocket bodies are already in orbit and will contribute to uncontrolled reentries for decades to come.” Each of those events sends a spray of fragments through the atmosphere, and while most fall over ocean or sparsely populated land, the sheer number of passes means that some will intersect with the high-density lanes that connect North America, Europe and Asia.

Controllers and pilots on the front line

The people who first have to manage this new class of hazard are not astronauts or satellite operators but air traffic controllers and airline crews. When a reentry is predicted, controllers may be asked to reroute flights or close segments of airspace, often with limited warning and incomplete data on exactly where fragments will fall. One recent analysis described how Air traffic controllers now have something new to worry about, as parts left over from rockets and satellites increasingly fall through airplane flight paths.

There is already a playbook for what happens when the risk is judged too high. During one high-profile reentry, Spanish and French authorities temporarily closed portions of their skies, a move that a later review said showed how closing airspace to avoid collisions can greatly reduce the chance that an aircraft will be struck. Those closures, however, come at a cost in delays, diversions and fuel burn, which is why regulators are pushing for better forecasting and clearer communication from launch providers.

What the FAA and regulators are learning

Regulators are only beginning to quantify this risk in the same way they do for bird strikes or runway incursions. In a 2023 analysis, But the Federal Aviation Administration calculated preliminary numbers on the risk to flights, focusing on how a single impact could threaten the lives of all on board. Those figures are still being refined, but they mark an important shift: space debris is moving from a theoretical concern into the formal safety cases that underpin airspace management.

Regulators are also learning the hard way how much they depend on accurate, timely information from launch companies when something goes wrong. After a failed SpaceX mission, an internal review found that The FAA found that SpaceX did not alert controllers through proper channels once the rocket failed, leaving Controllers based in key centers scrambling to protect aircraft without a clear picture of the debris field. That episode has intensified calls for stricter oversight of commercial space operations and more robust protocols for notifying aviation authorities when a vehicle breaks up.

Space weather, turbulence and a crowded sky

Falling hardware is not the only space-related threat that airlines are being forced to take more seriously. Space weather, particularly solar storms that disturb the upper atmosphere and radio communications, is emerging as a parallel risk that can compound the challenges of managing reentries. A recent investigation into an airline safety fault described how Warning shot for the future was the phrase used for a mishap that grounded dozens of flights and exposed how vulnerable some systems are to disturbances from above.

That same report drew a line back to an October 2008 incident in which some 40 passengers suffered fractures and other injuries when an aircraft suddenly pitched down, with space weather among the factors examined before several others were ruled out. The lesson regulators took from that case is that the boundary between aviation and space is more porous than it looks on a route map. As more debris and more energetic solar activity intersect with ever denser traffic, the margin for error shrinks.

Economic fallout: delays, diversions and new costs

Even when nothing is hit, the economic impact of managing reentry risk is already measurable. Airlines have to plan for potential diversions, carry extra fuel, and build more slack into schedules on days when large objects are expected to come down. In some regions, carriers are starting to factor this into their long-term planning, treating debris as a kind of environmental variable that can disrupt operations in the same way as storms or volcanic ash.

Industry observers in India have gone so far as to describe orbital debris as a “new climate” threat, arguing that it will shape how airlines and airports operate in the coming decades. One analysis noted that Reentries force airspace closures, disrupting routes for thousands of flights and imposing costs that are ultimately borne by passengers and cargo customers. That framing helps explain why airlines, which have no control over what is launched into orbit, are increasingly vocal about the need for stricter debris mitigation rules.

Public perception and the communication gap

For travelers, the idea of metal falling from space into their flight path is understandably unsettling, yet most people have little sense of how the risk compares to more familiar hazards. Aviation agencies and scientists are trying to strike a balance between transparency and reassurance, emphasizing that the absolute probability of a strike is low while acknowledging that the trend line is moving in the wrong direction. That nuance can be hard to convey in a news cycle that often favors dramatic visuals of fiery reentries.

Broadcast segments have started to grapple with this tension, explaining that more space junk is accumulating in orbit around Earth and that it poses a threat to all of us when it re-enters the atmosphere, even if the most likely outcome is still a harmless splashdown. As I see it, the communication challenge is to help passengers understand that aviation remains extraordinarily safe while also making clear why regulators and airlines are pushing for changes in how rockets and satellites are designed, flown and disposed of.

What needs to change in space and aviation policy

The emerging consensus among experts is that the most effective way to protect aircraft is not to armor jets or radically alter flight paths, but to reduce the number of uncontrolled reentries in the first place. That means designing satellites and rocket stages to burn up more completely, reserving fuel for controlled deorbit burns, and enforcing end-of-life disposal rules that keep dead hardware from lingering in orbit for years. Some of these practices are already in place for newer constellations, but the backlog of older objects, including those reentries for decades to come, will continue to pose a hazard.

On the aviation side, I expect to see more formal integration of reentry forecasts into flight planning tools, along with clearer lines of authority for when and how airspace should be closed. The experience of Spanish and French authorities shows that decisive action can sharply cut the risk to aircraft, but it also highlights the need for consistent global standards so that carriers are not left guessing. As launch rates climb and more countries and companies put hardware into orbit, the pressure will grow for an international regime that treats falling space junk not as an exotic anomaly but as a routine safety factor to be managed, much like weather or volcanic ash.

Supporting sources: Risk of falling space junk impacting planes is growing, experts warn.

More from MorningOverview