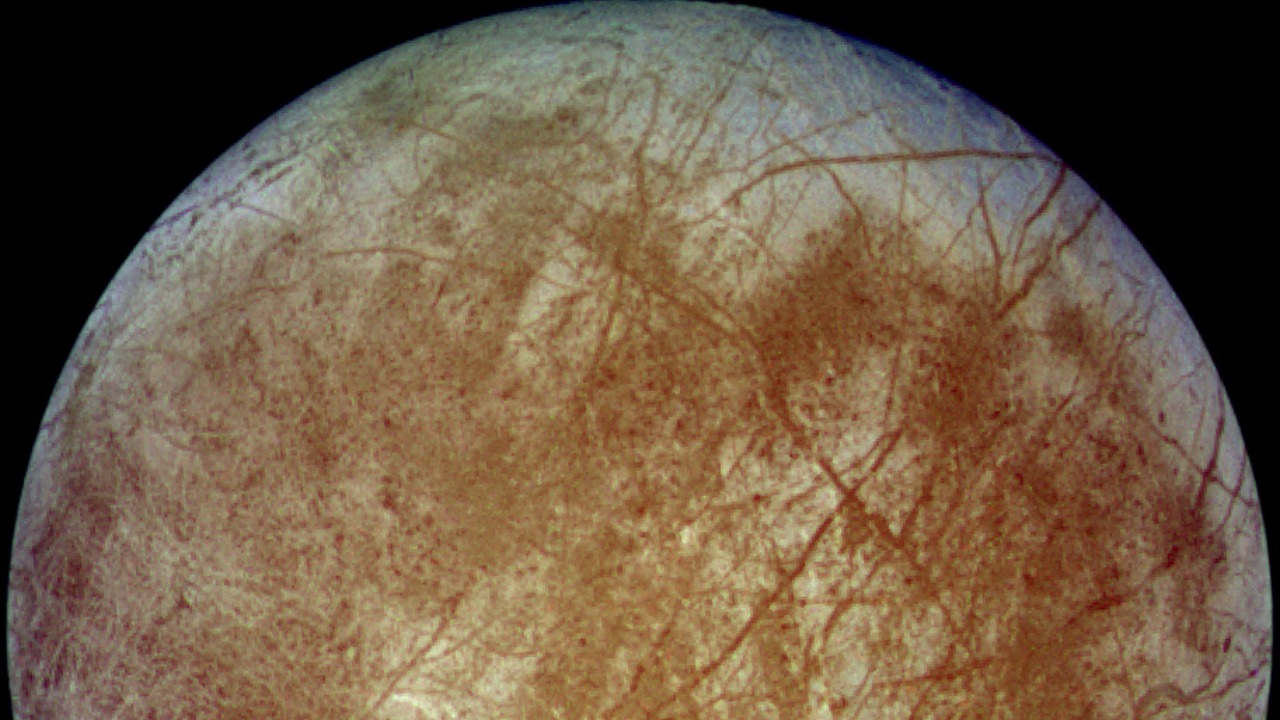

For decades, Jupiter’s moon Europa has been cast as one of the solar system’s best bets for alien life, a world with a global ocean hidden beneath ice. New modeling now suggests that this ocean may sit atop a crust that is far quieter and more rigid than many scientists hoped, raising the possibility that Europa’s seafloor lacks the restless geology that helps sustain life on Earth.

Instead of a churning interior that constantly reshapes the crust, the new work points to a largely frozen engine, with limited faulting and weak tidal heating. If that picture holds, Europa’s ocean could be chemically starved and physically stagnant, a place where life might struggle to gain a foothold even if liquid water has persisted for billions of years.

Europa’s layered world and the promise of a hidden ocean

Europa has always stood out because, like our planet, it appears to be a differentiated world with an iron core, a rocky mantle, and an overlying ocean of salty water capped by ice. According to Structure data, that ocean likely sits between a dense interior and a relatively thin outer shell, a configuration that naturally invites comparisons to Earth’s own oceans. Unlike Earth, however, Europa’s surface is a frozen crust marked by fractures and ridges rather than continents and seas, so any potential biosphere would have to make do in permanent darkness beneath kilometers of ice.

That basic architecture has made Europa a prime target for missions that can probe beneath the surface. The Juno spacecraft has already flown past Jupiter and its moons, collecting gravity and magnetic data that help refine estimates of Europa’s interior. Building on that foundation, NASA’s dedicated Europa Clipper mission is designed to map the ice shell, sample the tenuous atmosphere, and search for signs that the ocean interacts with the surface, all key clues to whether this layered world is truly habitable.

A quiet seafloor and a crust that barely moves

The new research that has unsettled Europa optimists focuses on how much the moon’s crust actually flexes and fractures. Modeling of the ice shell and interior suggests that Europa’s icy outer shell is relatively thick and mechanically strong, which would limit the amount of active faulting that can occur as the moon orbits Jupiter. One analysis describes how Europa’s icy exterior may not deform enough to generate the vigorous tidal heating once assumed, implying a crust that is more static than dynamic.

At the ocean floor, that rigidity translates into a world where, as one modeling study puts it, “Geologically, there is not a lot happening down there. Everything would be quiet.” The same work, which examines how faults might cut through the ice and into the rocky interior, concludes that Europa’s seafloor may lack the kind of active faulting and volcanism that feed hydrothermal systems on Earth. In that scenario, Geologically driven heat and chemical exchange would have been stronger in the distant past, but today the ocean floor could be comparatively inert.

Why a still crust is bad news for potential life

On Earth, life in the deep ocean thrives where geology is loudest, at mid-ocean ridges and hydrothermal vents that tap into a hot, active mantle. The new Europa work, led by planetary scientist Paul Byrne in the field of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences, challenges the assumption that Europa’s seafloor offers similar energy-rich environments. If the rocky core is not being vigorously fractured and heated, then the ocean above it may receive only a trickle of fresh minerals and chemical gradients, the very ingredients that power chemosynthetic ecosystems on our planet.

That concern is echoed in broader coverage of the study, which notes that Europa might not be “geologically alive” in the way astrobiologists had hoped. Reporting from WASHINGTON highlights how the findings cast doubt on the long-standing idea that Europa’s ocean floor hosts robust hydrothermal activity. While the authors are careful not to declare the moon barren of life, the implication is clear: a still crust and a calm seafloor would make it far harder for complex ecosystems to emerge, even if microbes could eke out an existence in isolated pockets.

Oxygen, ice thickness, and the limits of habitability

Even if Europa’s interior is muted, the surface environment offers some tantalizing resources, especially oxygen created when radiation splits water molecules in the ice. Earlier work using data from NASA’s View of Jupiter’s system suggested that Europa has enough oxygen to support a million people, at least in terms of raw production. A separate analysis, based on Jupiter’s moon observations, concluded that Europa generates enough oxygen to keep a million people alive for a day, underscoring how intense radiation and ice chemistry can stockpile oxidants at the surface.

More recent modeling, however, complicates that optimistic picture. Using Data compiled from NASA’s Juno mission, researchers argue that Europa, Jupiter’s ice cloaked ocean world, actually lacks sufficient oxygen in its ocean to make it comfortably hospitable. The key uncertainty is how efficiently oxidants created in the surface ice can be transported downward through the shell. Work on the ice thickness, including simulations that liken migrating ice blocks to a planetary “snowball fight,” stresses that, However the shell is structured, the likelihood of Europa hosting life depends strongly on how that ice moves and how heat is distributed around the moon’s rocky core, as highlighted in However.

Recalibrating expectations as Europa Clipper closes in

The new modeling arrives just as NASA’s flagship mission to Europa is on its way. The agency launched a spacecraft from Florida to study Jupiter’s moon Europa for signs of life, a mission explicitly designed to test whether the ocean and ice shell could support biology. That spacecraft, Europa Clipper, will perform dozens of close flybys, measuring the thickness of the ice, mapping surface composition, and sniffing for any plumes that might vent material from the ocean below. A new study suggests Jupiter’s moon may not offer the conditions once imagined, but the mission’s instruments are precisely what scientists need to confirm or challenge the “quiet ocean” hypothesis.

Public interest in Europa’s habitability has been fueled not only by technical papers but also by accessible coverage that frames the stakes. One report notes that Jupiter’s moon has long been one of the most tantalising targets in the search for extraterrestrial life, thanks to its subsurface ocean, but warns that the internal engine that once powered vigorous geology may have cooled. Another account, focused on where NASA spacecraft are bound, underscores that Europa might not have the conditions for life if it is not “geologically alive.” Together with the detailed modeling that finds Europa’s ocean floor is surprisingly calm, these reports are pushing scientists to recalibrate expectations, not to abandon the search, but to refine what “habitable” really means on an ice covered world.

That recalibration is evident in how researchers now talk about the new work. One summary of the modeling, framed under the banner of Jan and the phrase Scientists Say Europa, Ocean May Be Too Quiet for Life, emphasizes that the study challenges the idea of a Living Seafloor. The authors stress that a still crust and limited tidal heating could mean the ocean is less chemically rich than hoped, as described in A new study. At the same time, they caution that a quiet ocean does not automatically mean a lifeless one, and that only detailed measurements from Europa Clipper and continued analysis of Juno’s observations will reveal whether Europa’s crust is too still for life to thrive or simply calm on the surface while subtle processes continue in the dark.

More from Morning Overview