Life’s most indispensable molecules are not the serene, unchanging fixtures they might appear to be. Even the proteins that guard our DNA and keep cells alive are constantly tweaking their structures to fend off new threats, locked into a cycle of adaptation that never quite ends. Biologists now see these essential proteins as participants in a molecular arms race, forced to evolve just fast enough to stay in place.

That paradox, stability built on ceaseless change, is reshaping how I think about genomes. From the tips of chromosomes to the front lines of antiviral defense, the same pattern keeps surfacing: vital protein complexes must preserve core functions while responding to enemies that are always probing for weaknesses.

The Red Queen sets the rules of the game

The idea that survival depends on running just to stay in place traces back to Lewis Carroll’s story in which Alice meets a monarch who never stops sprinting. In that scene from Through the Looking-Glass, the Red Queen explains that the landscape itself is shifting, so standing still is not an option. Evolutionary biologists borrowed this image to describe how species locked in conflict, such as hosts and parasites, must continually adapt simply to avoid falling behind.

In modern terms, the Red Queen hypothesis captures the logic of an evolutionary arms race, where each side’s gain is the other’s loss and neither can declare permanent victory. That framework now extends down to the level of individual molecules, where proteins and genetic elements chase one another across generations. The same story that began with Alice running beside a queen now helps explain why some of the most conserved parts of the genome still carry the scars of rapid, relentless change.

Essential proteins at chromosome ends face moving targets

Nowhere is this tension between stability and change more vivid than at the ends of chromosomes, where specialized structures called telomeres protect DNA from fraying. Protecting chromosome ends is not optional, because broken or unguarded telomeres can trigger catastrophic rearrangements or cell death. Yet the proteins that assemble at these sites must also recognize and neutralize genetic invaders that try to exploit the same DNA sequences.

Recent work on protecting chromosome ends shows how a pair of essential protein partners can navigate this dilemma. These molecules are indispensable for telomere protection, yet they also respond to ongoing genetic threats that try to hijack telomeric DNA. The result is a delicate compromise: the complex must keep its grip on chromosome ends while subtly altering its surface to recognize and block new attackers, a molecular version of upgrading a lock without ever changing the door.

Mia Levine’s molecular battleground

Research led by Mia Levine pushes this story deeper into the mechanics of how essential proteins adapt without breaking. Her work focuses on a vital DNA protection protein complex that sits at the interface between genome maintenance and conflict. This complex has to preserve a functional, threat-resilient genome, which means it cannot afford to lose its basic role in shielding DNA even as it responds to new molecular assaults.

By tracking how specific amino acid changes accumulate in this complex, Mia Levine and her colleagues show that evolution often targets flexible regions that can tolerate variation while leaving the core machinery intact. But this battleground presents a fundamental puzzle that has long vexed scientists: how do life’s most essential, stable proteins remain robust while still evolving rapidly at their contact points with genetic threats. The same complexes that are indispensable for telomere protection must therefore carry both deeply conserved domains and rapidly shifting surfaces, a split personality written into their sequences.

Selfish DNA and a genome at war with itself

The arms race is not only between hosts and external pathogens. Inside the human genome, mobile DNA sequences known as retrotransposons behave like internal saboteurs, copying and pasting themselves into new locations. These “jumping genes” can disrupt vital coding regions or regulatory circuits, yet over long stretches of time they also acquire regulatory roles in the genome, blurring the line between parasite and partner.

Geneticists describe this as an evolutionary arms race with itself, in which the genome encodes both the selfish elements and the proteins that restrain them. The conflict between DNA retrotransposons and the host genes that silence them leaves signatures of rapid evolution in proteins that are otherwise part of basic housekeeping. What looks like a static instruction manual is in fact a record of repeated skirmishes, with essential regulators constantly adjusting to keep mobile elements in check without shutting down the useful sequences that those same elements sometimes provide.

Housekeeping receptors caught between iron and infection

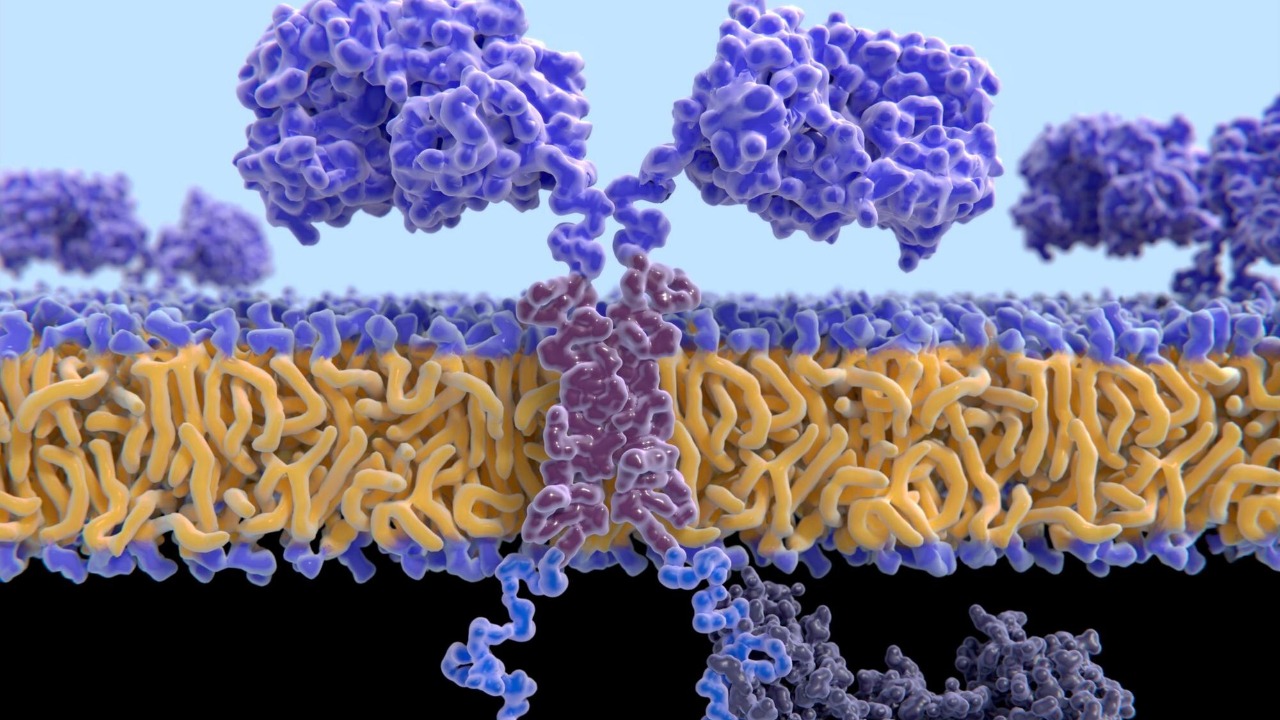

Some of the clearest evidence that essential proteins are pulled into arms races comes from receptors that perform mundane but crucial cellular chores. The transferrin receptor, often abbreviated as Transferrin receptor or TfR1, is a textbook example. Its primary job is to act as the cell-surface receptor for iron-loaded transferrin circulating in the blood, importing iron that is needed for metabolism and DNA synthesis.

Yet this same receptor has been repeatedly co-opted by viruses that use it as a doorway to trigger their own cellular entry. In a detailed Introduction to this system, researchers describe how the transferrin receptor’s essential role makes it a tempting target, since the cell cannot simply discard it to block infection. Because these sensors can be so effective at detecting invaders, viruses often encode proteins that antagonize them or their downstream effectors, forcing the host to tweak receptor surfaces and signaling pathways without compromising iron uptake. The transferrin story shows how even a basic nutrient transporter can become a contested gateway when pathogens evolve to exploit it.

Innate immune sensors and the cost of vigilance

On the front lines of antiviral defense, essential proteins that sense foreign genetic material are under especially intense pressure. Protein kinase R, often abbreviated as PKR, is a member of a family of kinases that respond to double-stranded RNA produced during viral replication. This molecule acts as a dsRNA sensor with broad antiviral activity, shutting down protein synthesis in infected cells and buying time for other immune responses to mobilize.

Because PKR is so central to early defense, viruses have evolved a wide array of countermeasures that bind, block, or degrade it. An PROTEIN KINASE R SENSOR WITH BROAD antiviral reach cannot remain static when every new viral lineage is probing for vulnerabilities. Recent studies have identified numerous host cell restriction factors that constitute the first line of defense against viruses, and many of these show signatures of positive selection, with ratios of nonsynonymous to synonymous changes greater than 1 indicating adaptive evolution. That pattern, highlighted in Jan reports on host restriction factors, underscores how innate immune sensors pay a continual cost in mutational churn to keep pace with viral innovation.

Dual host–virus arms races reshape core cellular tools

When an essential protein is pulled into conflict with pathogens, it often ends up serving two masters: the cell that depends on it and the virus that tries to hijack it. Dual host–virus arms races can therefore reshape even the most basic housekeeping proteins. In the case of transferrin receptor 1, the same extracellular loops that bind iron-loaded transferrin also provide docking sites for viral glycoproteins, creating a structural overlap between nutrition and infection.

Because these sensors can be so effective at detecting and responding to invaders, pathogens evolve proteins that antagonize them or their downstream executioners, as detailed in Because analyses of host–virus interactions. The result is a tug-of-war over the same molecular surfaces, with host mutations that reduce viral binding sometimes also impairing normal function. I see this as a recurring theme: evolution is not free to optimize defense in isolation, it must constantly negotiate trade-offs with the everyday jobs that keep cells alive.

How essential complexes evolve without falling apart

The puzzle that “But this battleground presents a fundamental puzzle” hints at is how essential complexes can change at all without collapsing their core functions. One answer emerging from telomere and immune studies is modularity. Proteins often contain distinct domains, some of which are rigid and conserved, while others are flexible and exposed. Evolution tends to concentrate rapid change in the latter, especially at interfaces where proteins contact DNA, RNA, or other proteins that may belong to pathogens or selfish elements.

In the telomere system, for example, the complexes that are indispensable for telomere protection appear to preserve their DNA-binding cores while allowing loops and tails to diversify. That pattern aligns with the description that But and How these proteins preserve essential biological functions while adapting to new threats. I read this as a kind of evolutionary compartmentalization: the parts of the protein that must never fail are shielded from change, while the parts that interact with a shifting cast of enemies are allowed, even encouraged, to experiment.

Bi-stability landscapes and the limits of innovation

Even with modularity, there are hard constraints on how far essential proteins can wander through sequence space. New functional proteins are likely to evolve from existing proteins, but most existing proteins are already finely tuned to their roles. An analysis of evolutionary dynamics on protein bi-stability landscapes argues that many proteins sit near thresholds where small changes can flip them between active and inactive states, or between properly folded and misfolded conformations.

In this view, described in a detailed Introduction to bi-stability, new functions often arise after gene duplication, when one or both gene copies can accumulate mutations without immediate catastrophic loss of function. Sep analyses of these landscapes emphasize that most proteins, however, are constrained by the need to maintain stability, which limits the directions evolution can explore. I see this as the physical backdrop to the arms race: essential proteins can adapt, but only along narrow ridges of sequence that preserve their structural integrity.

From lab sensors to classroom Red Queens

What ties these disparate systems together is the idea of sensing and response. In the lab, researchers dissect how a dsRNA sensor like PKR or a cell-surface sensor such as the transferrin receptor detects danger and triggers downstream defenses. These molecular sensors are not optional extras, they are woven into core processes like translation and iron uptake, which is why pathogens target them so aggressively.

In classrooms, educators use the Red Queen story to make this abstract logic tangible. A PBS LearningMedia segment on the Red Queen asks why asexual organisms should be more parasitized than sexual reproducers living right beside them, given that they are all being exposed to the same parasites. The answer circles back to genetic variation and the ability to keep pace with evolving threats. When I connect that teaching example to the molecular data, the message is the same: whether we are talking about whole organisms or single proteins, survival depends on staying in the race, not on reaching a finish line.

Why this endless race matters for medicine and evolution

Understanding that essential proteins are locked into ongoing arms races is not just an academic exercise, it has direct implications for medicine. Antiviral drugs that target PKR pathways, for instance, must account for the fact that both host and virus are already engaged in rapid adaptation. Therapies that manipulate transferrin receptor 1 to block viral entry cannot ignore its central role in iron metabolism, or the likelihood that viruses will evolve around any single intervention.

At the same time, recognizing the genome as a battleground with itself, where retrotransposons and host regulators coevolve, reframes how I think about genetic variation and disease risk. The same mobile elements that once behaved as selfish DNA now contribute to regulatory networks, yet they remain potential sources of instability. From essential proteins at telomeres to innate immune sensors and housekeeping receptors, the picture that emerges is of life built on moving ground, where even the most fundamental molecules are shaped by conflict that never fully ends.

More from MorningOverview