For more than a century, the double-slit experiment has been the sharpest test of what reality is made of, and of whether Albert Einstein or Niels Bohr had the better grasp of the quantum world. Now a new generation of “idealized” double-slit tests, from ultracold atoms in Massachusetts to single atoms in a Chinese lab, is being hailed as the moment the debate finally tips in Bohr’s favor. The experiments do not dethrone Einstein’s relativity, but they do show, with unprecedented clarity, that on the smallest scales nature behaves in the strange, probabilistic way Bohr insisted it must.

What has changed is not the basic setup, which still involves particles passing through two slits, but the precision and control with which physicists can now watch the process unfold. By stripping the experiment down to its quantum essentials and pushing the measurements to extremes, teams at MIT and in China have produced results that many researchers see as a definitive answer to a 98‑year argument about whether particles have well defined paths or only fuzzy possibilities until they are observed.

How a century-old argument came down to two slits

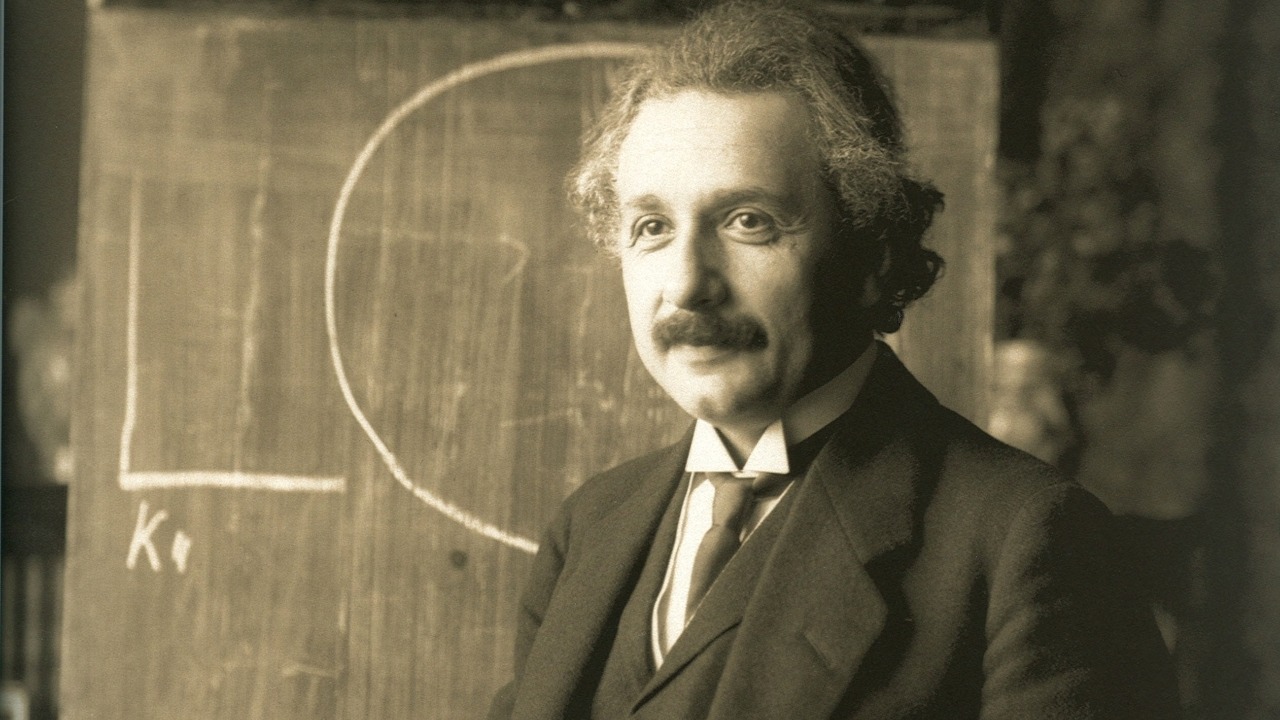

The clash between Einstein and Bohr was never just about equations, it was about what kind of world those equations describe. Einstein believed that even in quantum physics, particles like photons and atoms should have definite properties and trajectories, whether or not anyone is looking, and he treated the apparent randomness of measurements as a sign that the theory was incomplete. Bohr, by contrast, argued that quantum objects do not possess sharp values until they are measured, and that the wave of possibilities encoded in the mathematics is as real as anything we can picture.

The double-slit experiment became the arena where those philosophies met. When particles are sent one by one through two narrow openings, they build up an interference pattern on a screen, as if each particle were a wave that passed through both slits at once and interfered with itself. Einstein tried to imagine ways to track which slit each particle used without destroying that pattern, hoping to show that the wave description was only an approximation, while Bohr maintained that any attempt to gain “which-path” information would inevitably erase the interference. The new work at MIT, described as “A Century On, MIT Proves Einstein Wrong: Bohr Was Right In The Most Famous Quantum Experiment” in a report on Century On, is explicitly framed as a modern replay of that original challenge.

Inside MIT’s “idealized” double-slit experiment

What makes the latest MIT work so striking is how close it comes to the textbook thought experiment that generations of students have seen on chalkboards. Instead of light beams and crude detectors, the team used a cloud of exactly controlled ultracold atoms, arranged so that each atom could play the role of a quantum particle passing through a pair of slits. By cooling and trapping these atoms, the researchers could prepare them in nearly identical states and then let them evolve in a way that mimics the classic setup, but with far more control over every variable than earlier optical versions.

According to detailed accounts of the project, the group relied on 10,000 ultracold atoms to settle what is described as a 98-year debate between Einstein and Bohr, using the atoms as a kind of quantum fluid that could be split and recombined with exquisite precision. In this “idealized” configuration, the interference pattern that emerged was not a messy blur but a clean, high contrast signature of wave behavior, and the team could systematically test how the pattern responded when they tried to extract information about the atoms’ paths. The result was exactly what Bohr’s view predicts: whenever the setup was adjusted to reveal which way the atoms went, the interference faded.

What “Einstein Was Wrong” really means

Headlines declaring that Einstein was wrong are easy to write and hard to interpret, because they can sound as if his entire legacy has been overturned. In reality, what the new double-slit tests show is that one specific line of argument he pursued against quantum mechanics does not hold up when the experiment is realized in its purest form. Einstein’s hope was that a clever measurement could expose hidden details about a particle’s path without disturbing the delicate interference pattern, revealing a deeper layer of reality beneath the probabilistic wave description.

The MIT work, described in one account under the banner “Einstein Was Wrong” and as an Idealized Double Slit Experiment Ends Nearly Year debate, shows that when the experiment is stripped of technical imperfections, the trade off Bohr described between interference and which-path knowledge is absolute. In that sense, Einstein was wrong on this one point, while his broader contributions, from special relativity to the photoelectric effect, remain untouched. The phrase “Einstein Was Wrong” is therefore best read as a verdict on a specific philosophical bet he made about quantum theory, not as a wholesale rejection of his physics.

Stripping the experiment to its quantum essentials

One of the most important aspects of the MIT work is how carefully the team eliminated classical distractions that might muddy the quantum story. In many earlier versions of the double-slit experiment, imperfections in the slits, vibrations in the apparatus, or thermal noise in the environment could blur the interference pattern or mimic the loss of coherence that Bohr’s argument predicts. By working with ultracold atoms in a highly controlled trap, the researchers could reduce those effects to the point where the only significant disturbances were the ones they deliberately introduced.

A detailed description of the setup emphasizes that the physicists performed an Audio supported, “idealized” version of the famous experiment, in which the double-slit behavior was recreated using matter waves in a way that could be tuned almost like a musical instrument. By “stripping to quantum essentials,” they ensured that the interference pattern was a direct expression of the atoms’ wave nature, not an artifact of the equipment. When they then added mechanisms to gain partial or full information about the atoms’ paths, the resulting degradation of the pattern could be traced cleanly to the quantum principle that knowledge of the path and the visibility of interference are mutually exclusive.

China’s “Exceptionally Precise” single-atom test

While the MIT experiment used a large ensemble of atoms to recreate the double-slit scenario, a separate effort by Chinese physicists attacked the Einstein–Bohr debate from another angle, focusing on the behavior of a single atom interacting with a single photon. Their goal was to build an apparatus sensitive enough to detect the tiniest recoil of an atom when a photon passed by, without washing out the interference that arises when light behaves like a wave. This required an extraordinary level of control over both the atom and the light field, pushing the limits of current technology.

Reports from the Chinese Academy of Sciences describe the work as an Exceptionally Precise experimental triumph, noting that They constructed an advanced apparatus of extreme sensitivity that could register the atom’s motion while still allowing interference to form when no which-path information was extracted. In a complementary account, another report explains that When the trap holding the atom was loosened, the atom moved slightly, revealing the photon’s path, and at that moment the interference pattern vanished. This direct link between the atom’s recoil and the loss of interference is exactly what Bohr’s complementarity principle anticipates.

Bohr’s complementarity, 100 years on

To understand why these experiments are being hailed as decisive, it helps to revisit what Bohr meant by complementarity. In his view, wave and particle descriptions are not rival pictures of what is “really” happening, but mutually exclusive ways of organizing our observations. The same quantum system can display interference in one setup and behave like a stream of localized impacts in another, but it never shows both aspects at once. The choice of measurement defines which aspect becomes manifest, and there is no deeper story in which the particle secretly carries both a definite path and a fully formed interference pattern.

A recent analysis titled “Quantum physics Revisiting Bohr and Einstein, 100 Years On How a …” argues that The MIT experiment has reinforced Bohr’s viewpoint, but not in the simplistic way many clickbait headlines suggest, and it stresses that Bohr’s ideas were always more subtle than a crude “shut up and calculate” caricature. The same piece notes that the new data do not eliminate all alternative interpretations of quantum mechanics, but they do rule out the specific kind of path revealing measurement Einstein hoped might preserve classical intuitions. In that sense, Bohr emerges from the century long debate not as an unquestioned victor in every philosophical detail, but as the one whose core prediction about the trade off between knowledge and interference has been borne out with remarkable clarity.

What the results say about reality, not just equations

For non physicists, the natural question is what all this means for our picture of reality. The combined message of the MIT and Chinese experiments is that the quantum world resists any attempt to describe it in purely classical terms, even when the measurements are pushed to extremes of precision. Particles do not simply follow hidden trajectories that we have not yet learned to track, and interference patterns are not just optical illusions that would disappear if we had better detectors. Instead, the act of gaining information about a system’s path is inseparable from the disturbance that destroys its wave like behavior.

In practical terms, this reinforces the foundations of technologies that already rely on quantum weirdness, from superconducting qubits in Google’s Sycamore processor to the entangled photons used in satellite based quantum key distribution. These devices work precisely because interference and superposition are real physical resources that can be harnessed, not because of any hidden classical mechanism. By showing that even an “idealized” double-slit experiment behaves exactly as quantum theory predicts, the new results give engineers and theorists alike more confidence that the rules they are exploiting are not provisional. They are, as far as current evidence shows, a core feature of reality itself.

Why Einstein still matters after losing this round

It is tempting to treat the outcome of the double-slit saga as a simple scorecard, with Bohr chalking up a win and Einstein taking a loss. That framing misses how deeply Einstein shaped the very quantum theory he later criticized, and how his objections helped sharpen the questions that experiments are now answering. His work on the photoelectric effect introduced the idea of light quanta, his analysis of Brownian motion gave some of the first convincing evidence for atoms, and his debates with Bohr forced the physics community to confront the conceptual strangeness of the new theory rather than sweeping it under the rug.

Even in the context of the double-slit experiment, Einstein’s thought experiments were invaluable in exposing potential loopholes and pushing others to design more refined tests. The fact that modern teams at MIT and in China are still explicitly addressing scenarios he sketched nearly a century ago is a testament to the depth of his insight. Losing this particular argument about whether a clever measurement could preserve both interference and definite paths does not diminish his broader legacy, and in a sense, the “Einstein wrong?” narrative is itself a product of the high standard he set for what a physical theory should explain.

More from MorningOverview