Deep beneath our feet, far beyond the reach of any drill, new research suggests that Earth’s center is far more intricate than a simple metal ball. Instead of a single solid sphere, the inner core appears to be built up in distinct shells, a layered structure that behaves a bit like an onion and records the planet’s deepest history. That emerging picture is forcing scientists to rethink how Earth formed, how it cools, and even how its magnetic field has managed to survive for billions of years.

By combining seismic readings from earthquakes with high pressure experiments that squeeze metal alloys to extremes, researchers are finding evidence that the core’s iron is arranged in multiple zones with different textures and compositions. Those hidden layers, stacked thousands of kilometers below the surface, may hold clues to why Earth, unlike its rocky neighbors, still has a strong magnetic shield and a dynamic interior.

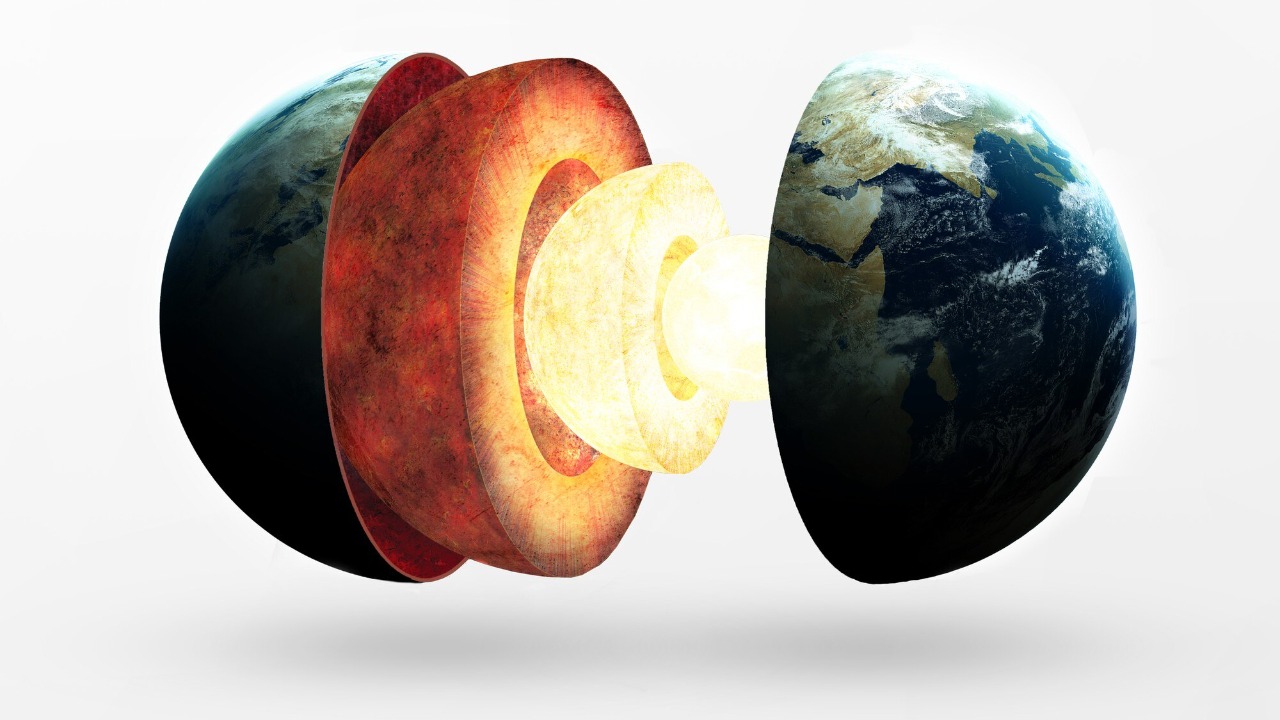

Peeling back the planet: what “onion-like” really means

When scientists describe Earth’s core as onion-like, they are not talking about thin skins you could peel with a knife, but about large, nested regions that differ in how atoms are packed and how waves move through them. The classic textbook view divides the planet into a crust, mantle, liquid outer core, and solid inner core, yet new work argues that the inner core itself is subdivided into several shells with distinct properties. In this view, each layer formed under slightly different conditions, leaving behind a stratified record of how the deep interior evolved over time, a picture that recent analyses of Earth’s core structure have started to sharpen.

Those layers are not visible directly, so researchers infer them from how seismic waves bend, slow, or speed up as they cross the planet. When waves from large earthquakes pass through the center, their travel times and paths subtly change, hinting at boundaries and textures that do not match a uniform sphere of iron. The new onion-style model suggests that the inner core has at least two, and possibly more, nested regions with different crystal alignments and chemical makeups, stacked inside the surrounding liquid metal outer core that itself wraps around the solid center like a molten shell.

Seismic fingerprints of a hidden architecture

The strongest clues for layering come from seismology, the science of how vibrations travel through Earth. As waves generated by quakes cross the core, they split into different types and speeds, leaving behind a pattern that can be read like a fingerprint. Researchers have found that waves moving along certain directions pass through the inner core faster than those traveling at other angles, a sign that the material is anisotropic rather than uniform. That directional dependence, combined with subtle changes in wave behavior at specific depths, points to multiple internal zones instead of a single homogeneous mass, a conclusion supported by detailed modeling of seismic wave results.

Seismologists have long suspected that the inner core might have an outer shell and a deeper region with different crystal orientations, but the new work sharpens that boundary and suggests additional complexity. Some waves appear to slow down or scatter more in a shallow inner core layer, then speed up again deeper inside, as if they are crossing from one fabric of iron to another. By comparing thousands of wave paths, scientists can map those transitions and test whether they align with changes in temperature, composition, or both, building a three dimensional picture of the core’s architecture without ever touching it.

Lab-made cores: recreating PETRA III pressures

Seismic data alone cannot reveal exactly what the inner core is made of, so experimentalists have turned to powerful X ray machines to mimic the crushing conditions at Earth’s center. In Hamburg, teams working at the PETRA III facility have used intense beams to probe tiny samples of iron alloys while squeezing and heating them to extremes that approach core conditions. Those high pressure and high temperature X ray diffraction experiments show how iron atoms arrange themselves into different crystal structures, and how those structures respond to stress, providing a physical basis for interpreting the anisotropic behavior seen in seismic waves and supporting the idea that High pressure tests at PETRA III in Hamburg reveal a layered inner core.

By systematically varying temperature and pressure, researchers can map out which phases of iron and alloy mixtures are stable at different depths, then compare those patterns with the seismic fingerprints from the real planet. If a particular crystal structure produces the same directional wave speeds that seismologists observe, it becomes a strong candidate for a given layer in the inner core. The Hamburg experiments suggest that certain arrangements of iron and light elements can form shells with distinct textures, which would naturally create the onion-like stratification inferred from seismic data and help explain why some regions of the inner core deform more easily than others.

A new state of matter at the center of Earth

Layering is only part of the story, because the material in the inner core does not behave like ordinary solid metal. Recent theoretical and experimental work points to a superionic state, a strange phase where some atoms sit in a fixed lattice while others flow through it almost like a liquid. In this scenario, Earth’s solid inner core is not rigid steel but a dynamic medium where carbon and other light elements move relatively freely within a framework of iron, a behavior that helps resolve a long standing seismic mystery about why waves travel the way they do through the deepest interior, as highlighted by Scientists studying a new state of matter at Earth’s center.

In this superionic phase, the inner core is technically solid but can deform and flow over long timescales, more like very stiff butter than like hardened steel. New research indicates that Earth’s solid inner core is actually in such a superionic state, where carbon atoms flow freely through the iron lattice, changing how heat and electricity move through the region and influencing the magnetic field. That work, which describes how the material is closer to butter than to steel, shows that the deepest layers of the planet occupy a regime of matter that is neither conventional solid nor liquid, a conclusion drawn from simulations and experiments summarized in New findings on Earth’s superionic core.

Carbon, iron, and the chemistry of inner core layers

The onion like structure is not just about different crystal orientations, it is also about chemistry. A key idea in the latest models is that mixtures of carbon and iron separate into distinct zones as the core cools, creating shells with slightly different compositions. Those compositional layers would change how dense each region is, how it conducts heat, and how it responds to stress, which in turn would affect seismic wave speeds and the behavior of the magnetic field. A recent synthesis of theory and experiment argues that such mixtures can naturally produce an onion-like layered structure in the inner core, a scenario explored in detail in work described as Scientists May Have Finally Solved the Puzzle of Earth, Inner Core Layers.

As the inner core grows over geological time, iron crystallizes out of the liquid outer core, leaving behind a fluid enriched in lighter elements like carbon. That process can create compositional gradients, with some layers richer in carbon and others more iron dominated, each with its own physical signature. The resulting stratification would not only explain the seismic anisotropy but also help regulate how heat escapes from the core, influencing the vigor of convection in the outer core and the long term stability of the geodynamo that powers Earth’s magnetic shield.

Deformed, less solid, and constantly evolving

Even with layering and superionic behavior, the inner core is not a static object. Evidence is mounting that its outermost regions can deform and flow over time, blurring the line between solid and liquid. A recent study of seismic data suggests that the near surface of the inner core may undergo viscous deformation, meaning it can slowly change shape under stress rather than behaving as a perfectly rigid sphere. That work, which describes a Deformed inner core that is less solid than previously thought, indicates that the boundary between the inner and outer core is more dynamic than once assumed, a conclusion supported by analyses summarized under the phrase Deformed inner core.

If the outer layers of the inner core can creep and distort, that motion could interact with the surrounding liquid metal, altering patterns of flow that generate the magnetic field. It might also help explain why some seismic waves show evidence of scattering and attenuation near the inner core boundary, as if they are passing through a region that is partially melted or mechanically weaker. Over millions of years, such deformation could rearrange the onion-like shells, thickening some layers and thinning others, and perhaps even shifting the orientation of the inner core relative to the rest of the planet.

Why the onion core matters for Earth’s magnetic shield

The structure of the inner core is not just an academic curiosity, it is central to understanding why Earth still has a strong magnetic field while other rocky worlds have lost theirs. The geodynamo that powers the field depends on heat and compositional convection in the liquid outer core, which in turn are controlled by how the inner core grows and how its layers release energy. If the inner core is stratified into shells with different compositions and superionic properties, each layer could contribute differently to the flow of heat and light elements into the outer core, shaping the patterns of motion that sustain the field.

Some models suggest that compositional layering can act like a throttle, regulating how quickly the core cools and how vigorously it convects. A layered inner core might help preserve a stable magnetic field over billions of years by smoothing out abrupt changes in heat flow, while still allowing enough energy to drive the geodynamo. The discovery that the inner core is less rigid and more complex than once thought also raises the possibility that changes in its structure could be linked to long term variations in field strength, magnetic reversals, or even subtle shifts in Earth’s rotation, though many of those connections remain active areas of research and are Unverified based on available sources.

A time capsule of Earth’s thermal history

One of the most intriguing implications of the onion model is that each layer may preserve a snapshot of conditions at the time it formed. As the inner core grows outward, new shells crystallize at the boundary with the outer core, locking in information about temperature, composition, and pressure at that moment. Over deep geological time, this process could build up a stratified archive of Earth’s thermal and chemical evolution, with older layers buried near the center and younger ones closer to the edge. Researchers argue that the proposed layered structure would preserve a unique archive of Earth’s thermal history over deep geological time, effectively turning the core into a time capsule of Earth’s interior across the ages.

Decoding that archive will not be easy, since scientists cannot sample the core directly, but they can use seismic data, high pressure experiments, and numerical models to infer how each layer formed and evolved. By matching the properties of different shells to plausible formation scenarios, they can reconstruct when the inner core first started to crystallize, how quickly it has grown, and how its chemistry has changed. That reconstruction could shed light on why Earth’s magnetic field turned on when it did, how the planet’s interior cooled compared with Mars or Mercury, and what that means for the long term habitability of worlds with similar structures.

From abstract models to public imagination

For non specialists, the idea of a layered core can feel remote, but it is beginning to filter into popular explanations of how the planet works. Visuals that show nested shells of iron and alloy at the center of Earth help bridge the gap between abstract physics and everyday understanding, turning a complex set of seismic and experimental results into a simple mental image. Reports describing how There may be hidden layers to Earth’s core dictated by chemical composition, and how Lab experiments suggest Earth’s inner core is structured in multiple shells, have helped bring the concept into wider view, as reflected in coverage that notes There, Earth, and Lab evidence for an onion-like structure.

At the same time, detailed news features have highlighted the human side of this research, profiling scientists who spend careers interpreting tiny changes in wave speeds or building diamond anvil cells to crush metals to unimaginable pressures. One such account, written by David Nield, explains how seismic waves passing through Earth reveal a complex inner structure and notes that temperatures in the deep interior can reach figures like 51 C (1508 °F) in certain experimental contexts, illustrating the extreme conditions under discussion and showing how David Nield connects Structure, Earth, and the 51 C (1508 °F) benchmark. Those narratives help translate a highly technical field into a story about how humanity is gradually peeling back the layers of its own world, one seismic echo at a time.

More from MorningOverview