Commonwealth Fusion Systems has crossed two thresholds that fusion watchers have been waiting on for years: a giant superconducting magnet now sits inside its experimental reactor, and a fresh alliance with Nvidia and Siemens aims to turn that machine into a living, learning software model. Together, the hardware milestone and the artificial intelligence push are meant to shrink the distance between a lab-scale device and a commercial power plant. I see the combination as a test of whether fusion can move at the pace of the broader tech industry rather than the glacial tempo of traditional energy projects.

The company is betting that a mix of high‑temperature superconductors, advanced manufacturing and AI‑driven simulation can turn its SPARC reactor into a template for future plants. If that bet pays off, the same tools now being built with Nvidia could eventually guide construction of a full‑scale facility, including the Ark power plant planned in Virginia, and give investors who already put up $863 m fresh confidence that fusion is edging out of the realm of science fiction.

The first SPARC magnet finally moves from factory to reactor

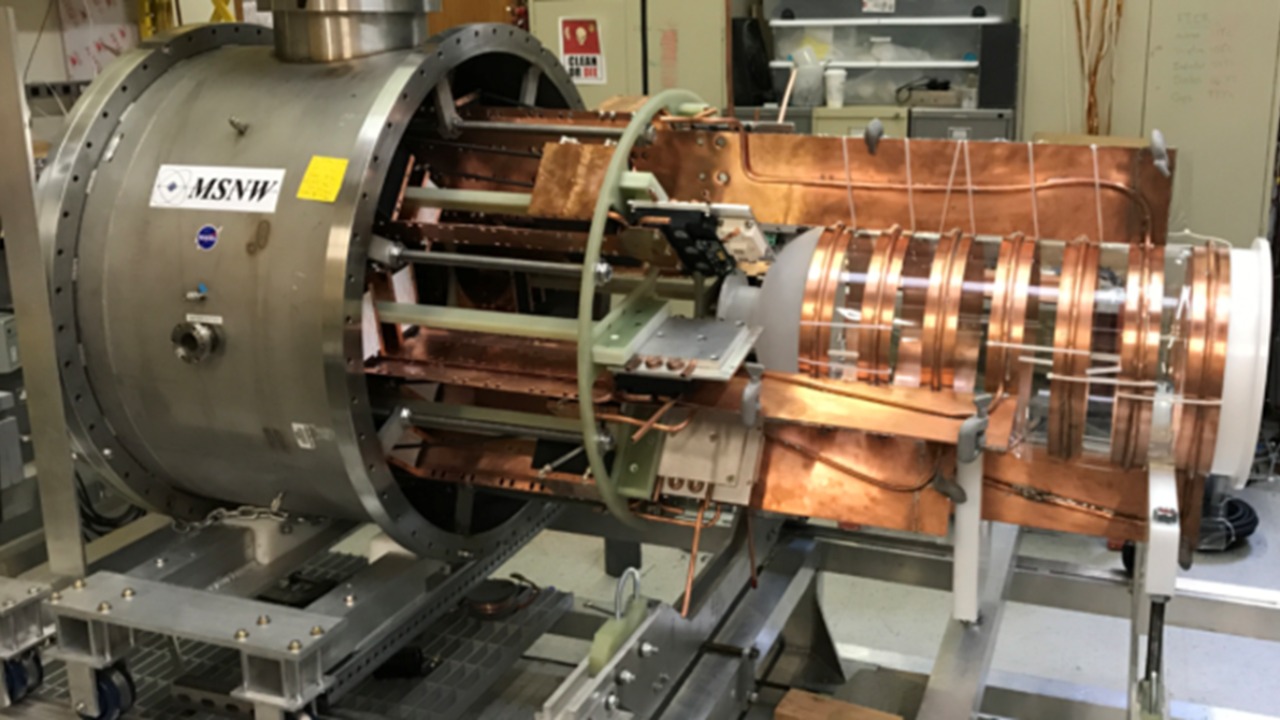

The most tangible news is that Commonwealth Fusion has installed the first of its massive superconducting magnets inside the SPARC fusion device, a step that shifts the project from component testing to actual reactor assembly. The company has been working toward this moment for years, because these magnets are what will generate the intense magnetic fields needed to squeeze plasma hot enough to fuse hydrogen isotopes, and the first unit is described as the initial piece in a set of 18 that will ring the machine. In its own description of the milestone, Commonwealth Fusion frames this as proof that its magnet technology is ready to be integrated into a reactor environment rather than just a test stand.

That first magnet is not a small lab coil, it is one of 18 superconducting units that will eventually form a complete toroidal cage around the plasma, and the company stresses that each is designed to generate fields strong enough to confine fuel at temperatures where fusion reactions become self‑sustaining. The installation shows that the complex logistics of moving, aligning and securing such a magnet inside the SPARC vacuum vessel are now being worked through on real hardware, not just in CAD models. A separate description of the project notes that the first of 18 superconducting magnets is already in place, underscoring that the rest of the ring will follow a proven installation path rather than a theoretical one.

Inside SPARC’s high‑field magnet strategy

SPARC’s design revolves around high‑temperature superconducting tape, which allows the magnets to run at much higher fields than conventional copper coils or older low‑temperature superconductors. That choice is central to the company’s claim that a relatively compact device can still reach the conditions needed to fuse hydrogen isotopes, because stronger fields let engineers shrink the overall machine while keeping the plasma stable. Earlier technical descriptions of the project explain that Commonwealth Fusion Systems plans to use these high‑field magnets to heat and compress plasma to fusion conditions, and that the installed magnet is the same type of coil that will eventually surround the full device to heat and compress it in operation.

From an engineering perspective, getting one of these magnets into SPARC is a test of more than just lifting capacity, it validates the interfaces between the coils, the cryogenic systems that keep them superconducting and the structural supports that must withstand enormous electromagnetic forces. The company has described the magnet installation as a manufacturing milestone that will be followed by a steady cadence of additional coils, and in a separate note it told POWER that this Manufacturing Milestone is part of a broader plan to complete the full magnet array by the end of the summer, which would put SPARC on a path toward integrated commissioning rather than isolated component tests.

Nvidia and Siemens bring an AI “digital twin” to fusion

In parallel with the hardware work, CFS has turned to Nvidia and Siemens to build a detailed digital twin of the SPARC reactor, a move that effectively treats the machine as both a physical object and a software platform. The idea is to create a high‑fidelity virtual replica that can mirror the behavior of the real device, so engineers can test control strategies, maintenance procedures and design tweaks in simulation before they touch the actual reactor. The company has said that this approach will let it compress years of manual experimentation into weeks of virtual optimization, and that the collaboration with Nvidia and Siemens is intended to Compress Years Into Weeks by using AI to explore operating scenarios that would be too risky or time‑consuming to try on the real machine.

In practical terms, that means feeding data from SPARC’s sensors into a simulation environment that runs on Nvidia hardware and Siemens industrial software, then training AI models to predict how the plasma and the machine will respond to different inputs. CFS has described the project as an AI‑powered digital twin that will help it design, operate and manage SPARC’s complex assemblies, and one report notes that CFS partners with Nvidia, Siemens specifically to build this AI digital twin for the SPARC fusion reactor, with the explicit claim that it will aid in accelerating the path to commercial fusion.

From Devens to Las Vegas: selling the fusion story at CES

Commonwealth Fusion Systems is not keeping this work behind closed doors. The company, based in DEVENS, Mass, has said that a visual illustration of the digital twin will be unveiled at CES 2026 in Las Vegas, a choice that signals it wants to pitch fusion not just to energy insiders but to the broader tech and investor community that gathers there each year. By bringing a detailed visualization of SPARC’s virtual counterpart to the consumer electronics stage, CFS is effectively arguing that fusion belongs in the same conversation as AI chips, autonomous vehicles and next‑generation displays, and that its collaboration with Nvidia and Siemens is as much a software story as a hardware one.

In its own announcement, CFS framed the CES appearance as part of a push to accelerate commercial fusion with Siemens and Nvidia by leveraging AI‑powered digital twins, and it highlighted that the visual model will show how data flows from the machine to the simulations and back again. The company said that A visual illustration of the digital twin will be used to demonstrate how AI can help tune reactor performance, optimize maintenance and inform the design of future plants, turning what might otherwise be an abstract physics project into something that looks and feels like a modern industrial software platform.

Big Tech money and the $863 million bet on CFS

The Nvidia deal is not happening in a financial vacuum. Earlier funding rounds already pulled some of the largest names in technology and finance into CFS’s orbit, including Nvidia itself, Google and Bill Gates, who collectively backed a major capital raise that framed fusion as the next energy revolution. One account of that round describes it as a bet by Big Tech and Japanese trading houses that fusion can move from experimental devices to commercial plants within a decade, and it notes that Big Tech Titans Including Nvidia, Google And Bill Gates Back what is described as an $863 Million Bet On Nuclear Fusion As Next Energy Revoluti, led in part by Mitsubishi and Mitsui.

Another breakdown of the financing emphasizes that the round totaled $863 m, or $863 million, and that it was raised by nuclear fusion startup Commonwealth Fusion Systems, which also goes by CFS. That report lists Nvidia alongside other strategic investors and stresses that the company is using high‑temperature superconducting tape to build its magnets, a detail that ties the funding directly to the hardware now being installed in SPARC. In that context, the new AI partnership looks less like a one‑off deal and more like a deepening of an existing relationship, with Nvidia moving from investor to technical collaborator as CFS deploys the $863 m it has already raised to build both physical and digital infrastructure.

From SPARC to Ark: the first grid‑scale plant in Virginia

SPARC is not an end in itself, it is meant to be the stepping stone to a full‑scale power plant that can feed electricity into the grid. CFS has already announced that it will build its first power plant, called Ark, in Chesterfield County Virginia, and it has described that facility as the world’s first grid‑scale fusion power plant. In a presentation about the project, the company said that we just announced that we will build our first power plant Ark in Chesterfield County Virginia, and it framed Ark as the template for a fleet of future plants that could be replicated around the world if SPARC validates the underlying physics and engineering.

That link between SPARC and Ark is where the digital twin strategy becomes particularly important. If CFS can use AI‑driven simulations to understand how SPARC behaves under different conditions, it can feed those insights directly into the design of Ark’s larger magnets, cooling systems and control software, potentially shaving years off the typical design‑build‑test cycle for a first‑of‑a‑kind power plant. The company has suggested that lessons from SPARC will inform everything from the layout of Ark’s reactor hall to the way it connects to the local grid in Chesterfield County Virginia, and the same tools that visualize SPARC at CES in Las Vegas could eventually be used to model how Ark interacts with real‑world demand patterns and market rules.

Why CES and Nvidia matter for public perception

By choosing to announce key milestones at CES and to highlight its partnership with Nvidia, CFS is deliberately positioning fusion as part of the broader AI and semiconductor narrative that has captivated investors and policymakers. The company said on Tuesday at CES 2026 that it had installed the first magnet in its Sparc fusion reactor, tying the hardware achievement directly to the tech industry’s flagship event rather than a specialized scientific conference. In that announcement, Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) said that the magnet installation and the Nvidia deal were part of a broader push to accelerate the timeline for commercial fusion, effectively telling a CES audience that fusion is ready to be treated as a near‑term technology story rather than a distant research project.

That framing matters because it shapes how regulators, utilities and the public think about fusion’s role in the energy mix. By aligning itself with Nvidia, a company synonymous with AI acceleration, and by showcasing its work in Las Vegas rather than only in DEVENS, Mass, CFS is trying to tap into the momentum that has already driven massive investment into AI infrastructure and data centers. The company’s own messaging around the digital twin emphasizes that it will use AI to compress development cycles and manage SPARC’s complex assemblies, and a separate report on the partnership notes that Claims about accelerating the path to commercial fusion are central to how the deal is being pitched to that audience.

The stakes for fusion and the broader energy transition

All of this activity, from the first SPARC magnet to the Ark announcement in Virginia, is unfolding against a backdrop of intense pressure to decarbonize power systems without sacrificing reliability. Fusion has long been held up as a potential solution that could provide abundant, carbon‑free baseload power, but it has also been dogged by skepticism about timelines and cost. By securing backing from Nvidia, Google and Bill Gates, and by raising $863 Million in a single round, CFS has convinced a set of influential players that its approach is worth serious capital, and one account of that raise explicitly describes it as Million Bet On Nuclear Fusion As Next Energy Revoluti, underscoring that investors see fusion as more than a science project.If SPARC performs as designed and the AI‑driven digital twin delivers on its promise to compress years of experimentation into weeks, the implications would extend far beyond a single company. Other fusion startups and even traditional fission and renewables projects could adopt similar digital twin strategies, using AI and high‑performance computing to de‑risk complex engineering before steel is cut. At the same time, the very visibility that comes from CES stages and Nvidia partnerships raises the bar for delivery, because missed milestones will be judged not just by physicists but by markets that have already priced in rapid progress. For now, the snapped‑in magnet and the inked Nvidia deal mark a pivot point where fusion’s future will be shaped as much by software and capital flows as by plasma physics.

More from Morning Overview