China has moved from incremental tweaks to a sweeping reset of electric vehicle safety, mandating that traction batteries must not catch fire or explode even in severe crashes or abuse. The new rules, built around a “No Fire, No Explosion” principle, respond directly to public alarm over high‑profile EV fires and position Beijing to dictate how the next generation of batteries is designed worldwide.

By hard‑coding zero‑tolerance for thermal runaway into national standards, regulators are forcing carmakers and cell suppliers to rethink everything from chemistry to crash structures. I see this as a turning point: instead of treating battery fires as a statistical risk to be managed, China is treating them as a design failure that must be engineered out of the system.

From fire scares to a national mandate

Public confidence in battery vehicles in China has been shaken by a string of dramatic incidents, and regulators have clearly been listening. Earlier this year, a series of three EV fires in ten days left what one account described as “China’s E‑Car Confidence at Rock Bottom,” with “Passengers Were Lucky” used to underline how close some incidents came to tragedy. The report on “Three Fires in Ten Days” detailed how, even after earlier safety crackdowns, vehicles were still ending up in flames in urban streets and parking garages, keeping the issue in the headlines and on social media.

Those “Three Fires in Ten Days” were not isolated anomalies but the latest in a pattern that had already prompted “Stricter Regulations” in previous years, yet the same source noted that the country was “Still Caught in a position requiring clarification” on how safe its EV fleet really was. I read that as a tacit admission that piecemeal rules had not been enough, and that only a comprehensive standard targeting the root causes of thermal runaway could restore trust. Against that backdrop, the decision to move to a legally binding “No Fire, No Explosion” requirement looks less like regulatory overreach and more like a political necessity to shore up public faith in electrification after the China E‑Car Safety Crisis.

What “No Fire, No Explosion” actually requires

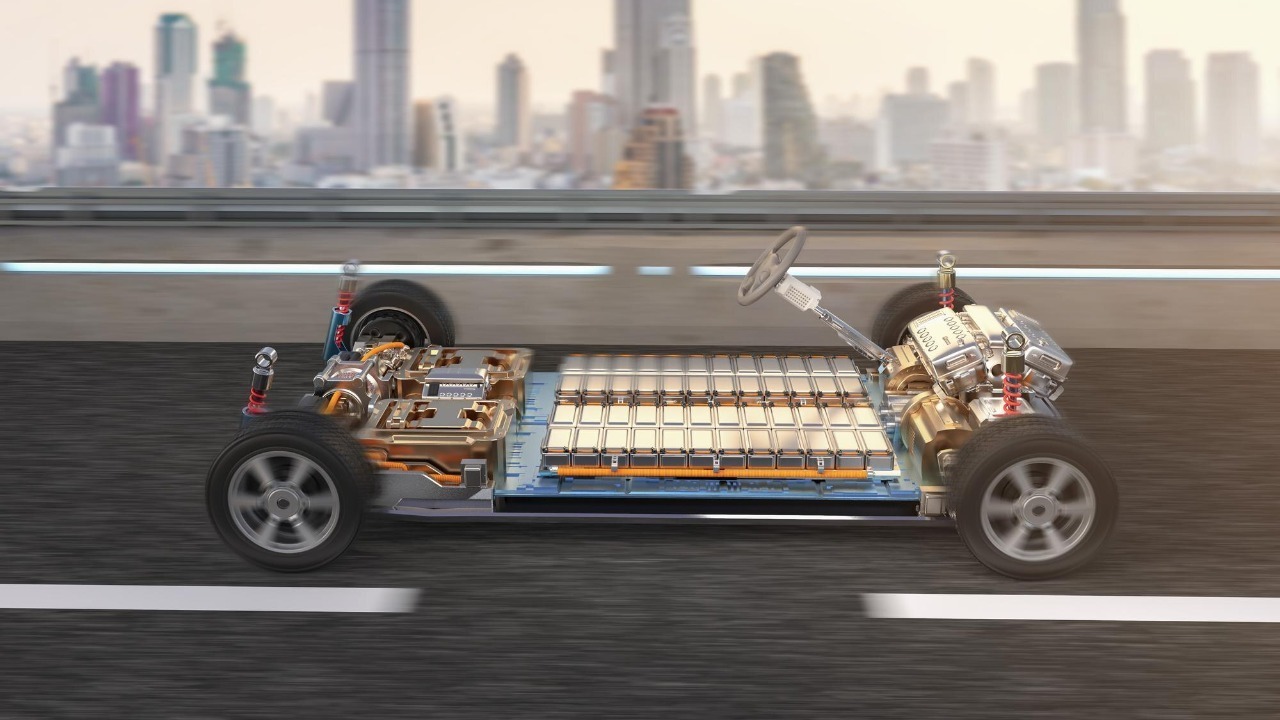

The core of the new regime is a national standard that, in plain language, bans battery packs from igniting or blowing up under a wide range of foreseeable stresses. In technical terms, the rules demand that lithium‑ion traction batteries must not enter uncontrolled thermal runaway, must contain any cell‑level failure so it does not propagate across the pack, and must maintain structural integrity in serious collisions and harsh environments. One detailed analysis of “No Fire, No Explosion, Safety Standards for EV Batteries” explains that the standard applies to lithium‑ion batteries used in electric vehicles and sets out performance criteria that go far beyond earlier norms, including requirements for abuse testing, thermal propagation resistance, and long‑term durability.

Another technical breakdown, titled “No Fire, No Explosion, China Sets New Global Standard for EV Battery Safety,” describes how the standard forces packs to survive repeated charge and discharge cycles, high and low temperature extremes, and mechanical shocks without triggering fire or explosion. I read that as a deliberate attempt to close loopholes where a battery might pass a narrow certification test but still fail in real‑world use. By insisting that “No Fire, No Explosion” must hold even under harsh environmental conditions and over many cycles, regulators are effectively telling manufacturers that safety margins must be built in from the cell chemistry up, not bolted on with software patches or last‑minute shielding, a point underscored in the China Sets New Global Standard for EV Battery Safety analysis.

GB 38031‑2025 and the 294‑standard safety overhaul

The flagship rule is the new GB 38031‑2025 standard, which codifies the “No Fire, No Explosion” mandate for traction batteries and sits within a much larger clean‑up of the regulatory landscape. Reporting on the rollout notes that China has finalized 294 national standards in one package, with GB 38031‑2025 singled out as the rule that will “enforce world’s first” zero‑tolerance requirements on EV battery fires and explosions. The same account stresses that the standard is not limited to lab conditions but is meant to apply in real‑world crashes and EV battery incidents, which is why it is being framed as a direct response to the spate of accidents that have dominated domestic coverage.

From my perspective, the sheer scale of the 294‑standard bundle signals that Beijing is not just tweaking one line of code in the rulebook but rewriting the operating system for its auto industry. The report on how “China mandates ‘No Fire, No Explosion’ EV battery rule as 294 national standards finalized” credits Adrian Leung with explaining that GB 38031‑2025 will sit alongside dozens of related rules on vehicle structures, charging systems, and emergency response, all designed to work together so that a crash does not cascade into a battery catastrophe. That integrated approach matters, because a pack that is thermally robust on paper can still fail if the vehicle’s underbody protection or crash management is inadequate, a risk the new framework is explicitly trying to eliminate through the GB 38031‑2025 mandate.

Bottom impact tests and the 2026–2027 compliance clock

One of the most striking features of the new rules is how specific they get about crash scenarios that have historically been under‑tested. A detailed explainer on how “China sets world’s strictest EV battery standard: ‘No Fire, Explosion’ rule effective July 2026” highlights a new bottom impact testing regime that evaluates how well the battery is protected when the underside of the vehicle strikes an obstacle. That focus on the “Bottom” of the car reflects a recognition that underfloor packs are vulnerable to speed bumps, debris, and curb strikes, which can puncture cells and trigger thermal runaway if not properly shielded. The same report situates the rule within a broader effort to “Understand China EV, Market” dynamics, noting that the country’s dense urban roads and varied infrastructure make such impacts more likely.

Timelines are tight but staggered. One technical overview notes that manufacturers must demonstrate compliance with the “No Fire, No Explosion, Safety Standards for EV Batteries” by July 1, 2027, giving the industry a defined window to redesign packs and validate new chemistries. Another report on how China will “introduce stricter EV battery standards in 2026” explains that the regulation goes considerably further on a technical level than previous rules, and warns that the cost and complexity of meeting the new requirements could weigh more heavily on smaller and mid‑sized companies. I read that as a clear signal that the 2026–2027 compliance clock is not just a safety deadline but a competitive filter, one that may accelerate consolidation among suppliers that cannot keep up with the demands of the stricter EV battery standards.

Why lithium‑ion batteries fail, and how the rules attack the risk

To understand why regulators are confident enough to promise “No Fire, No Explosion,” it helps to look at how lithium‑ion batteries fail in the first place. A technical deep dive titled “No Fire, No Explosion, Safety Standards for EV Batteries, Why Lithium, Ion Batteries Fail, Lithium” explains that lithium‑ion cells, including those used in electric vehicles, can enter thermal runaway when internal defects, overcharging, external heat, or mechanical damage cause temperatures to spike uncontrollably. Once one cell vents hot gases, neighboring cells can ignite in a chain reaction, turning a localized fault into a pack‑level fire or explosion. The same analysis notes that the new Chinese standard is explicitly designed to prevent that chain reaction, requiring that even if a single cell fails, the pack as a whole must not catch fire or explode.

In practical terms, that means the rules are pushing manufacturers toward thicker separators, more robust current interrupt devices, better thermal management, and pack designs that physically isolate groups of cells. The technical paper on “No Fire, No Explosion, Safety Standards for EV Batteries” also points out that compliance will require extensive abuse testing, including nail penetration, overcharge, and external short circuits, to prove that packs can withstand worst‑case scenarios without catastrophic outcomes. I see this as a shift from probabilistic safety, where a low failure rate is deemed acceptable, to deterministic safety, where the system must be engineered so that even when something goes wrong, the consequences are contained, a philosophy that is baked into the Why Lithium‑Ion Batteries Fail discussion.

From e‑bikes to SUVs: a safety net across the entire sector

Although the headline focus is on passenger cars, the new safety philosophy is being extended across the entire electric mobility ecosystem. One report notes that China has passed a new electric vehicle battery safety regulation that makes it the first country to mandate that batteries must prevent fires across the whole sector, including e‑bikes. That matters because smaller vehicles, from delivery scooters to shared bikes, have been involved in some of the most deadly battery fires globally, often in dense residential buildings where charging safety is lax. By pulling these segments into the same regulatory net, policymakers are signaling that “No Fire, No Explosion” is not just a slogan for premium SUVs but a baseline expectation for every lithium‑powered vehicle on the road.

The same account stresses that the law is a world first in requiring fire prevention as a legal obligation rather than a voluntary design goal, and that it covers not only complete vehicles but also the batteries supplied into them. I interpret that as a deliberate attempt to close the gap between high‑end EVs built by major automakers and the fragmented, sometimes informal supply chains that feed the e‑bike and light electric vehicle market. If a battery pack for a budget commuter scooter must meet the same fundamental safety criteria as one for a flagship sedan, then the entire ecosystem becomes less prone to catastrophic incidents, a point that is central to the world’s first EV battery safety law requiring fire prevention.

Industry front‑runners: CATL, BYD and the technology race

Not every manufacturer is starting from scratch. Some of China’s battery champions have been preparing for a “No Fire, No Explosion” world for years, and they are now positioning that head start as a competitive advantage. A detailed commentary on “Inside China’s New ‘No Fire, No Explosion’ EV Battery Mandate” notes that CATL launched its first‑generation “No Thermal Propagation” technology in 2020, achieving “no fire, no explosion” six years ahead of the new rules. That “No Thermal Propagation” design is built to prevent a failing cell from triggering its neighbors, exactly the behavior the standard now demands. I read this as evidence that regulators have been watching what leading firms like CATL can already do, then using that as a benchmark for what the rest of the industry must achieve.

Rival BYD is making similar claims. A report on how “China aims for global leadership in EV battery safety standards” quotes BYD as saying that its lithium iron phosphate LFP battery, branded as the “Blade Battery,” has already met the new standards. BYD also said in late May that the LFP Blade Battery, which is cheaper than ternary lithium batteries, has passed the required tests, including those designed to validate resistance to thermal runaway. If CATL’s “No Thermal Propagation” and BYD’s LFP Blade Battery are indeed compliant out of the gate, then the new rules could entrench their dominance, since smaller rivals will have to invest heavily to catch up with the safety performance that these leaders have already demonstrated in the LFP Blade Battery and CATL’s platform.

Global implications: a new benchmark for EV design

China is not just tightening its own rules, it is trying to set the template for how the rest of the world thinks about EV battery safety. One analysis of the new regulation notes that China has announced the world’s toughest EV battery safety rules, explicitly prohibiting fires and explosions and requiring that packs survive severe abuse without catastrophic failure. The same piece explains that the regulation is a world first in making such performance mandatory, and that it will apply to vehicles built by both domestic brands and foreign joint ventures operating in the country. In practice, that means global automakers that want to sell into the Chinese market will have to design packs that meet these standards, even if their home regulators have not yet caught up.

Another report on the new Chinese EV regulation explains that the rules are being introduced in a world where some manufacturers, including BYD Auto, already demonstrated advanced safety capabilities in 2022, and that others will need to develop or license similar technology by 2026–27 to remain competitive. I see a clear pattern here: China is using its scale as the largest EV market to export its safety philosophy, much as it has done with charging standards and battery supply chains. If “No Fire, No Explosion” becomes the de facto requirement for any serious player, then engineers in Europe, North America, and elsewhere will be designing to a Chinese benchmark, whether or not their own regulators have formally adopted the same rules, a dynamic highlighted in the new Chinese EV regulation coverage.

Zero tolerance and the future of EV trust

At the heart of this shift is a simple but radical idea: there should be “Zero tolerance for EV fire or explosions.” One account of the new rules uses that exact phrase to describe how China is setting mandatory requirements that leave little room for statistical trade‑offs between cost, performance, and safety. The same report notes that, in total, 113 national standards related to vehicles and energy systems are being updated alongside the battery rules, and that these changes are expected to reshape vehicle design from the ground up. I interpret that as a recognition that consumer trust is now as important a constraint as range or price, and that a single viral video of a burning EV can undo years of marketing about green mobility.

For engineers and executives, the message is blunt. If a battery pack can still plausibly catch fire or explode in a foreseeable scenario, then it is not good enough for the world’s largest EV market. The “Zero tolerance for EV fire or explosions” framing suggests that regulators will not be sympathetic to arguments about edge cases or rare events, especially after the “Three Fires in Ten Days” that left China’s E‑Car Confidence at Rock Bottom. Instead, they are betting that clear, strict rules will push the industry to innovate its way out of the problem, whether through chemistries like LFP, architectures like CATL’s “No Thermal Propagation,” or new structural protections such as the bottom impact tests described in the Zero tolerance analysis.

More from MorningOverview