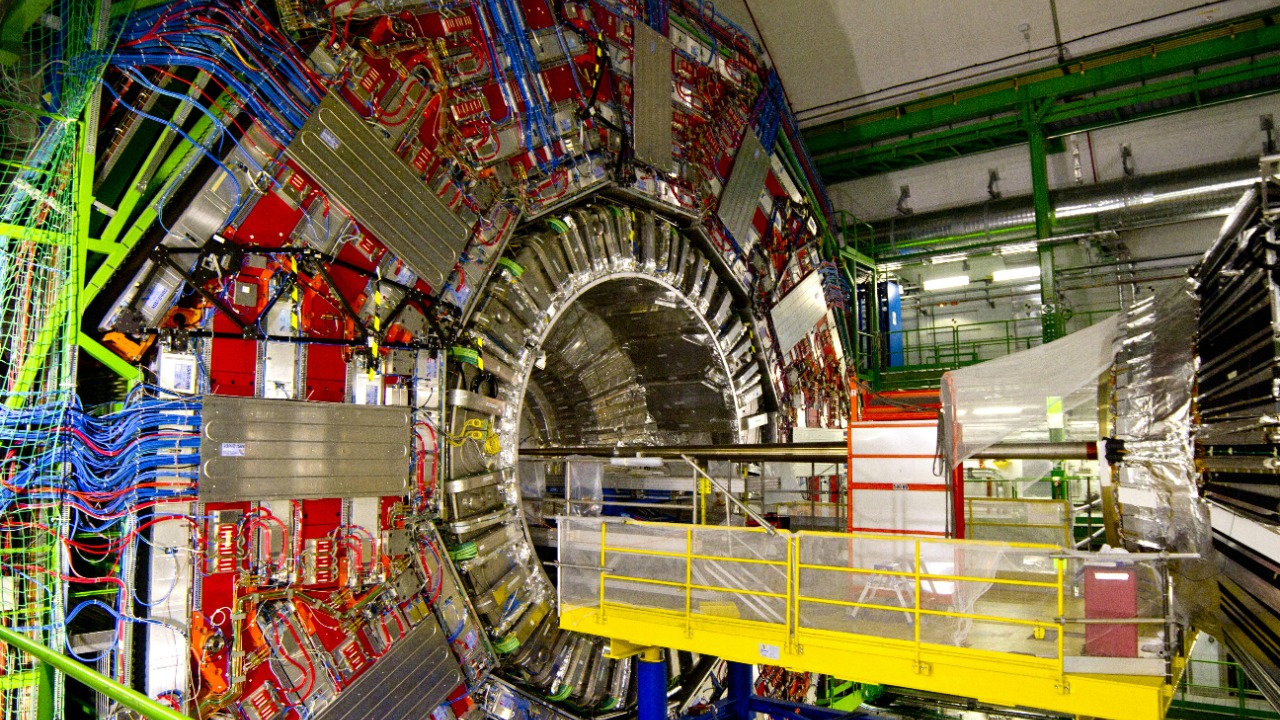

Inside the Large Hadron Collider, protons slam together at nearly the speed of light, creating a brief fireball of quarks and gluons that looks, at first glance, like pure chaos. New work from CERN physicists suggests that this apparent disorder hides a subtle pattern, a kind of internal choreography that shapes how matter emerges from those violent encounters. I see this as a shift in how we think about the subatomic world, from a picture of random debris to one of constrained possibilities and hidden structure.

Instead of treating each collision as a unique, unrepeatable mess, researchers are beginning to map out regularities in how particles are produced and correlated. That emerging order does not make the collisions any less extreme, but it does hint that the underlying rules of quantum chromodynamics, the theory that governs quarks and gluons, may be more elegantly organized than the raw data first suggests.

From boiling quark soup to patterned outcomes

When two protons collide at high energy, their constituent quarks and gluons briefly melt into a dense, hot medium often described as a boiling state of matter. In that instant, the number of ways those quarks and gluons could interact seems enormous, which has long encouraged the intuition that the resulting spray of particles is essentially random. Recent analyses of high-energy proton collisions, however, indicate that this intuition is misleading, because the final particles carry imprints of a more ordered process inside the fireball.

Physicists studying what happens inside high-energy proton collisions have found that quarks and gluons do not simply scatter in every direction with equal likelihood. Instead, they form a dense, correlated state before cooling into ordinary particles, and those correlations show up as preferred patterns in the angles and momenta of the debris. The discovery that this dense phase behaves less like a random explosion and more like a system with internal constraints is what researchers mean when they talk about hidden order in the chaos.

A new phase where “more” can mean “less”

The emerging picture is that, in an extreme phase of matter created in these collisions, particles appear to have far more ways to interact and transform than in the cooler, more familiar world outside the detector. Paradoxically, that abundance of possible interactions seems to give rise to a smaller set of effective outcomes, as if the system funnels itself toward particular configurations instead of exploring every option. I read this as a sign that the theory’s symmetries and conservation laws are asserting themselves in a collective way, guiding the evolution of the quark-gluon medium.

CERN scientists describe this regime as one where the internal degrees of freedom explode in number, yet the observable patterns of particle production become more structured, not less. In their account of a hidden order inside particle chaos, they emphasize that in this extreme phase, particles seem to have far more ways to interact and change than the smaller number of more ordered states that actually emerge, turning the problem into a puzzle we need to explore. That tension between microscopic freedom and macroscopic constraint is at the heart of why this result matters for fundamental physics.

Why hidden order matters for the Standard Model

For decades, the Standard Model has given remarkably accurate predictions for particle interactions, yet it often does so through calculations that treat complex collisions as statistical ensembles. The discovery of regular structures inside what looked like random sprays suggests that some of those statistical treatments might be hiding deeper organizing principles. If quark and gluon interactions in a dense medium naturally self-organize into a limited set of patterns, then the Standard Model’s equations may be encoding more emergent behavior than we have fully appreciated.

I see two big implications here. First, better understanding of this hidden order could sharpen tests of the Standard Model by reducing the theoretical uncertainties that come from treating collisions as messy backgrounds. Second, it could help physicists distinguish subtle signs of new physics from the structured noise of ordinary events. If the baseline “chaos” is actually patterned, then any deviation from that pattern becomes a clearer signal that something beyond the current theory is at work.

From collider data to real-world technologies

Although this work is rooted in abstract quantum fields, the idea that complex systems can hide simple organizing rules has a long history of spilling into technology. Techniques developed to analyze correlations in particle collisions have already influenced methods in medical imaging, such as positron emission tomography, and in data-heavy fields like network traffic analysis. As researchers refine tools to extract hidden order from collider data, I expect similar statistical and computational methods to migrate into areas like climate modeling, financial risk analysis, and even traffic optimization in large cities.

The conceptual lesson is just as important. When engineers design materials for quantum computers or advanced sensors, they are often trying to harness collective behavior among many interacting particles. The CERN findings reinforce the idea that even when individual interactions look wild, the ensemble can settle into predictable patterns. That mindset, treating apparent randomness as a clue rather than a barrier, is likely to shape how technologists approach everything from error correction in quantum processors to pattern recognition in large language models and other AI systems.

Reframing chaos at the smallest scales

What strikes me most about this research is how it reframes the story physicists tell about the smallest building blocks of matter. Instead of a universe that becomes more chaotic as we zoom in, we are seeing hints that new forms of order emerge at extreme energies and densities. The boiling quark-gluon state inside a proton collision is not just a fleeting mess, it is a laboratory for collective behavior that challenges our intuition about randomness and complexity.

As analyses of proton collisions grow more precise and theoretical models catch up with the data, I expect the language of hidden order to become more central to how we talk about high-energy physics. The work at CERN is not only mapping out the internal life of quarks and gluons, it is also offering a broader lesson about where to look for structure in complex systems. In a world that often feels chaotic at every scale, the idea that even the most violent particle collisions can harbor a quiet, underlying pattern is a reminder that nature’s rules are both stranger and more orderly than they first appear.

More from Morning Overview