Biologists have long treated cell membranes as passive barriers, thin skins that separate the chemistry of life from the chaos outside. A new line of research suggests they may be far more dynamic, behaving like microscopic generators that turn motion into electrical energy. If that picture holds up, it could reshape how I think about everything from nerve impulses to the design of future medical implants.

The emerging idea is simple but radical: the constant jostling and shape shifting of living cells might directly produce electrical signals, not just modulate them. Instead of electricity being only a byproduct of ion pumps and channels, the membrane itself could be an active player, converting mechanical motion into voltage in real time. That possibility is forcing researchers to revisit some of the most basic assumptions about how life powers its own information networks.

From cellular skin to active machine

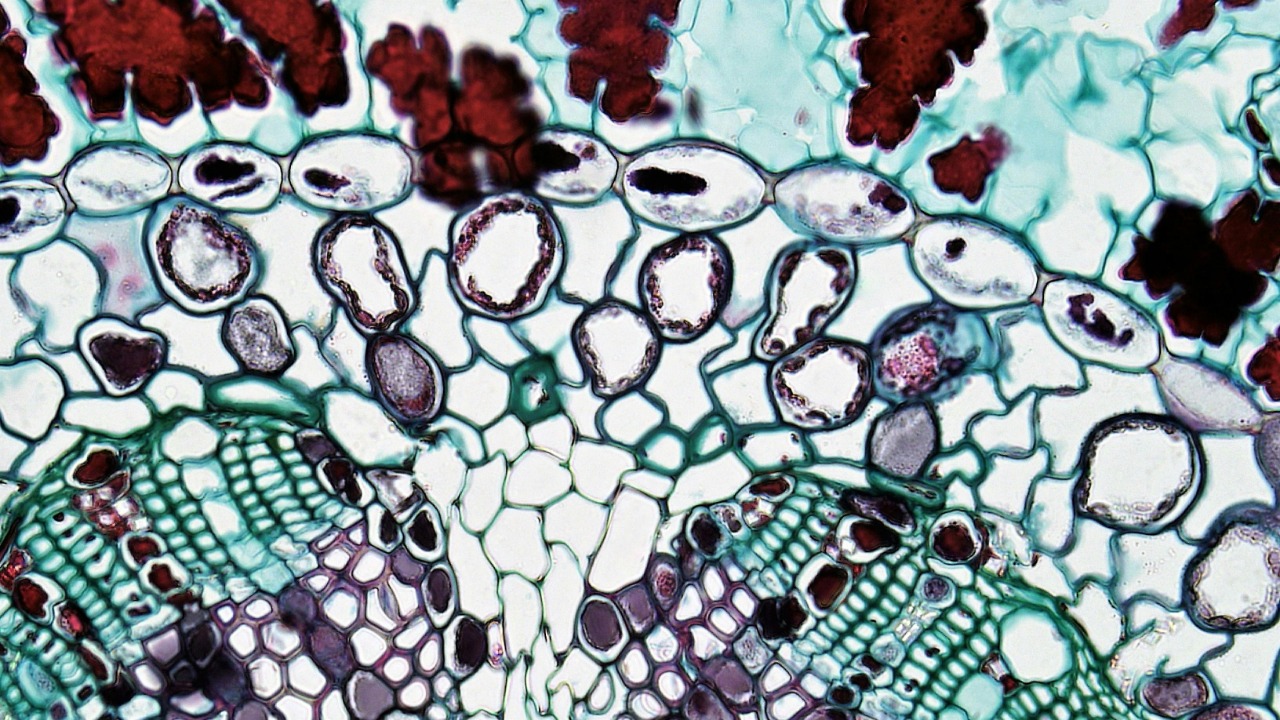

In textbooks, the cell membrane is usually drawn as a neat double line, a phospholipid bilayer studded with proteins that let specific molecules in and out. It is described as selectively permeable, chemically sophisticated, but essentially a static backdrop for the real action inside the cell. The new work challenges that static picture, arguing that the membrane’s constant rippling, bending, and stretching could itself be a source of electrical activity in living tissue.

Researchers studying these effects focus on how the bilayer behaves when proteins, lipids, and the surrounding fluid are all in motion. At microscopic scales, thermal noise, active protein reshaping, and cytoskeletal tugs never stop. According to recent experiments, these activities exert forces on the membrane that can subtly change its thickness and curvature, which in turn alters how ions are distributed across it. In carefully controlled systems, scientists have shown that this kind of motion could actively move ions and generate measurable voltages, a result that underpins the claim that cell membranes may act like tiny power generators.

The physics of a biological generator

At the heart of this idea is a familiar physical principle: when charges move in response to mechanical deformation, you can get electricity. In engineered materials, that effect shows up as piezoelectricity, where squeezing a crystal produces a voltage. In cells, the membrane is not a crystal, but it is a thin, flexible capacitor, with ions on each side forming charged layers. If the distance between those layers changes, or if the surface area fluctuates, the local electric field can shift in ways that push ions around.

In the new experiments, scientists treat the membrane as a soft, fluctuating capacitor that is constantly being driven out of equilibrium by the active processes of life. Proteins embedded in the bilayer change shape, the cytoskeleton pulls and releases, and the surrounding fluid buffets the surface. When these motions are strong and organized enough, they can create tiny pressure gradients and local flows that nudge ions along preferred paths. The result is a small but real electrical signal that does not require a traditional ion pump or channel to be switched on, but instead emerges from the membrane’s own restless motion.

How researchers caught cells in the act

Capturing such faint signals is not straightforward, so researchers have had to develop new tools to see whether living cells really do turn motion into electricity. In recent work, they combined high sensitivity electrical measurements with imaging that tracks membrane fluctuations at nanometer scales. By correlating the timing of mechanical ripples with spikes in voltage, they could test whether the two phenomena rise and fall together in a way that suggests cause and effect rather than coincidence.

To isolate the effect, scientists compared cells in different states, for example, with active metabolism versus chemically quieted conditions. When the internal machinery was humming, the membranes showed more pronounced undulations and the electrical readouts revealed richer patterns of spontaneous activity. When that machinery was damped down, both the motion and the electrical noise diminished. The data supported the idea that cells may generate their own electrical signals through microscopic membrane motions, rather than relying solely on classic ion channel firing.

Rethinking how cells communicate

If membranes themselves can convert motion into voltage, the implications for cell communication are significant. I was taught that electrical signaling in biology is dominated by well choreographed opening and closing of ion channels, especially in neurons and muscle cells. Mechanical effects were treated as modifiers at best, influencing how easily channels open but not serving as a primary source of charge movement. The new findings suggest that the baseline electrical noise in many cells may actually be a direct reflection of their mechanical life.

That reframing matters because cells constantly sense and respond to forces, from blood flow in arteries to stretching in lung tissue. If mechanical fluctuations are inherently tied to electrical signals, then every tug on a membrane could carry an electrical signature that neighboring cells can read. This would blur the line between mechanosensation and electrophysiology, turning the membrane into a hybrid device that couples the two. It also raises the possibility that some unexplained patterns of spontaneous activity in tissues might be rooted in subtle shifts in membrane motion rather than in hidden chemical triggers.

Energy budgets at the nanoscale

Another consequence of this work is a fresh look at how cells manage their energy budgets. Traditional models emphasize ATP driven pumps that maintain ion gradients, which are then tapped to power electrical events like action potentials. If membrane motion can directly move ions, then some fraction of a cell’s electrical landscape might be powered by mechanical work that is already being done for other reasons, such as reshaping the cytoskeleton or trafficking vesicles.

In that view, the membrane becomes a kind of energy recycler, harvesting a little bit of electrical work from mechanical tasks that the cell must perform anyway. The effect is not likely to replace ATP driven pumps, which remain essential for maintaining large gradients, but it could provide a background trickle of charge that fine tunes local potentials. Over billions of cells, even a modest contribution from this mechanism could add up, especially in tissues that are constantly in motion, such as the heart, the gut, or contracting skeletal muscle.

What this means for nerves and the brain

Nowhere is the interplay between electricity and biology more central than in the nervous system. Neurons rely on rapid, all or nothing spikes of voltage to transmit information, and those spikes depend on precise control of ion flows. If the membrane itself can feed into that process by turning mechanical fluctuations into small voltage shifts, then the threshold for firing might be more dynamic than standard models assume. Tiny changes in membrane tension or curvature could nudge a neuron closer to or further from firing, even without any change in synaptic input.

That possibility dovetails with long standing observations that physical forces, such as pressure on the skull or swelling in brain tissue, can alter neural activity in complex ways. It also offers a new lens on how neurons might integrate signals from their own internal movements, like the trafficking of synaptic vesicles or the growth and retraction of dendritic spines. If those structural changes carry an electrical echo through the membrane, then the brain’s wiring diagram is not just a map of connections, but also a constantly shifting field of mechanically tuned electrical landscapes.

Toward bio inspired power and sensors

Beyond basic biology, the notion of a membrane that doubles as a generator has obvious appeal for engineers. If living cells can turn random jostling into usable electrical signals, then synthetic membranes or soft materials might be designed to do the same. That could lead to ultra thin, flexible power sources that harvest energy from motion in the body, such as the pulsing of arteries or the expansion of lungs, to run low power sensors or drug delivery systems without bulky batteries.

Researchers already experiment with nanoscale devices that mimic aspects of cell membranes, including artificial lipid bilayers and polymer films that host ion channels. Incorporating mechanically responsive elements into those systems could create hybrid materials that respond electrically to bending, stretching, or fluid flow. In principle, a patch of such material on the surface of an organ could monitor its mechanical health by translating subtle changes in motion into diagnostic electrical patterns, borrowing directly from the strategies that living cells appear to use.

Open questions and experimental hurdles

For all its promise, the idea of membranes as generators still faces important questions. One challenge is quantifying exactly how much electrical power these mechanical effects can produce under realistic physiological conditions. The signals detected in controlled experiments are small, and it remains to be seen how they scale in complex tissues where many other sources of electrical noise are present. Distinguishing the contribution of membrane motion from that of conventional ion channel activity will require even more refined tools and clever experimental designs.

Another open issue is how universal the effect is across different cell types and organisms. Some cells, such as red blood cells, lack many of the active processes that drive strong membrane fluctuations, while others, like neurons and immune cells, are constantly reshaping themselves. Mapping where and when mechanical to electrical conversion is most important will help determine whether it is a niche curiosity or a core feature of cellular life. As those maps emerge, they will guide both theoretical models and practical applications, from interpreting brain signals to designing new classes of bio inspired electronics.

More from MorningOverview