Quantum entanglement has shifted from a philosophical puzzle to a design brief for engineers working at the scale of atoms, photons and phonons. As researchers learn to control this fragile correlation inside nanostructures, they are effectively building the wiring for future quantum networks, processors and sensors. I see the most interesting progress happening where abstract quantum rules meet very concrete devices carved from crystals only a few atoms thick.

From spooky action to engineered resource

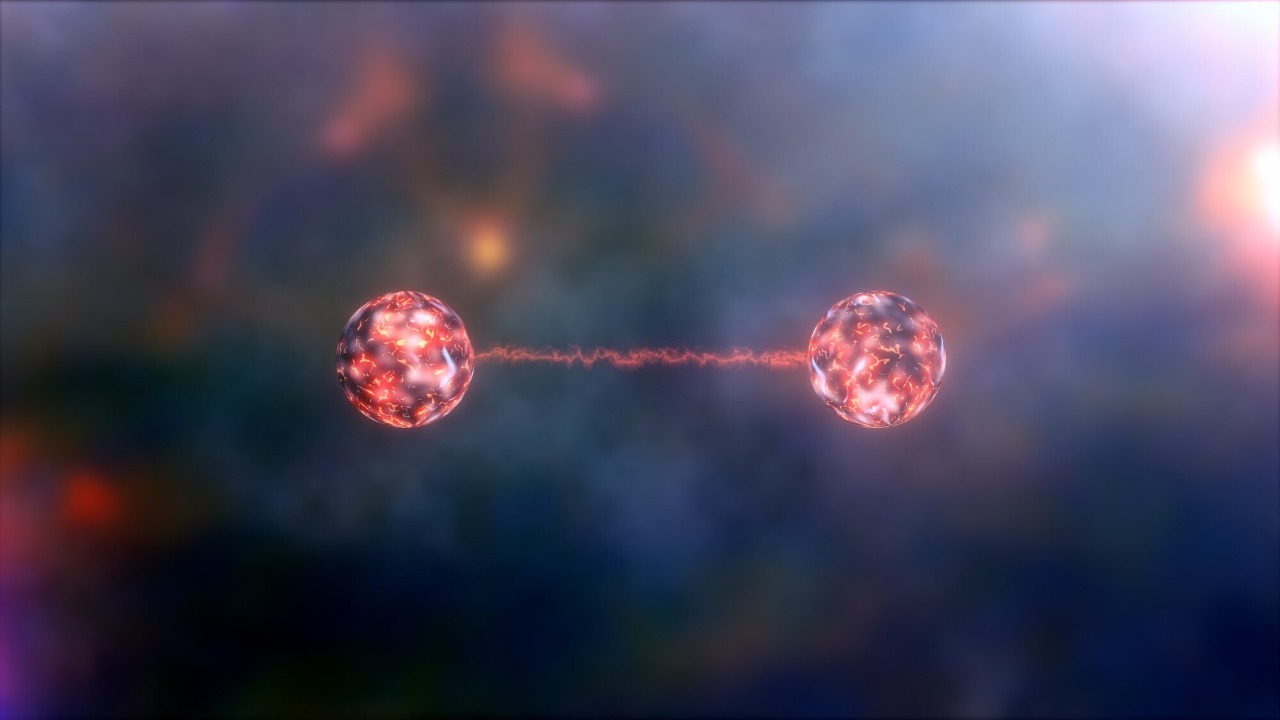

At its core, entanglement links the properties of particles so tightly that measuring one instantly constrains the state of the other, no matter how far apart they are. What once sounded like a paradox is now treated as a practical resource for quantum information, with theorists and experimentalists working out how to generate, distribute and measure these correlations on demand. As one overview of Entanglement at the nanoscale notes, these nonclassical links underpin protocols for secure communication, enhanced sensing and quantum computing.

Turning that conceptual power into hardware is difficult because entangled states are extremely sensitive to their surroundings. Any stray interaction with the environment tends to scramble the delicate quantum correlations that make entanglement useful. The same nanoscale structures that confine electrons, photons or phonons tightly enough to manipulate them can also expose those quanta to surfaces, defects and vibrations that accelerate decoherence, so the engineering challenge is to design devices that protect entanglement long enough to do something useful with it.

Why nanoscale platforms matter

Working at the nanoscale gives researchers access to regimes where quantum behavior is not a small correction but the dominant effect. Few-electron nanodevices, for example, can be tuned so that individual electrons occupy well defined quantum states whose interactions can be calculated and controlled. A detailed modeling effort on Few-electron double quantum dots highlights how such structures are being designed specifically to harness entanglement for quantum computing and sensing, rather than treating quantum effects as unwanted noise.

Nanoscale control also lets engineers sculpt the electromagnetic and vibrational environment around qubits, which is essential for both generating and preserving entanglement. By patterning materials into cavities, waveguides or pillar arrays, they can enhance desired interactions, such as photon emission into a particular mode, while suppressing loss channels that would leak information away. This level of tailoring is what turns abstract qubits into integrated components that might eventually sit inside a data center rack or a handheld device.

Van der Waals crystals and photonic entanglement

One of the most striking recent advances comes from thin crystals of so called van der Waals semiconducting transition metal compounds, where layers only a few atoms thick are stacked like sheets of paper. In a device built from these materials, researchers have shown that they can engineer quantum correlations in light at dimensions compatible with on chip integration. The work, described as a major step in Waals-based nanophotonics, relies on carefully aligning and contacting the crystals so that nonlinear optical processes generate entangled photons directly inside the layered structure.

That same effort is closely linked to the research program of Chiara Trovatello, who has focused on using these materials as compact sources for photonic quantum computing. In her description of the field, she argues that such platforms are Particularly promising for photonic quantum computing because they can act as integrated sources of entangled photon pairs, that is, qubits, without the need for bulky external crystals or fiber based setups. I see this convergence of materials science and quantum optics as a template for how entanglement will be embedded directly into future chips.

New flavors of entanglement in light

As devices shrink, researchers are not only generating more entanglement but also discovering new ways it can manifest. A recent experiment on nanoscale photonic structures showed that it is possible to entangle photons in previously unexplored degrees of freedom, expanding the toolkit for encoding information. Reporting on this work emphasized that It is possible to entangle photons in nanoscale systems in ways that could increase the capacity and robustness of transmitting information across space.

Another group has highlighted angular momentum as a less familiar but crucial property for structuring quantum light. By controlling how a photon spins or twists as it travels, they have identified One more channel through which entanglement can be created and manipulated, effectively multiplying the number of possible ways to encode qubits. I see these developments as evidence that the space of usable entangled states is still expanding, especially when nanostructures can sculpt light fields with subwavelength precision.

Sound as a quantum link: entangled phonons

Light is not the only carrier of entanglement at the nanoscale. In a striking result from Chicago, a team has used mechanical vibrations, or phonons, as quantum objects that can be entangled and controlled. The lead researcher, Aashish Chou, framed the achievement by saying that if you can imagine building a big quantum processor, their platform would be like a unit cell within that architecture, and the experiment was the first to entangle two phonons in a solid state device. This advance in Chou-led quantum sound shows that vibrations themselves can serve as qubits or as mediators between other quantum systems.

Using phonons as entanglement carriers is attractive because mechanical modes can couple strongly to both electronic and optical degrees of freedom, potentially acting as translators between different parts of a hybrid quantum device. At the same time, phonons are especially vulnerable to thermal noise, so the experiment required exquisite isolation and control to keep the vibrational quanta from dissolving into ordinary heat. I see this as a preview of future chips where electrons, photons and phonons are all entangled in a carefully orchestrated dance, each chosen for the task it performs best.

Nanoscale nodes for quantum networks

Entanglement becomes most powerful when it can be shared across distance, which is why so much effort is going into building quantum networks one node at a time. In one prototype, researchers fabricated an array of pillars a mere 120 nanometers high, each acting as a tiny optical antenna that can host quantum emitters and direct their photons into well defined channels. Described in the journal Nature Communications, this node architecture is designed so that individual pillars can be addressed and entangled, then linked to other nodes through optical fibers or waveguides.

Scaling beyond a single node requires strategies to distribute many entangled pairs in parallel, a task known as multiplexing. A team at Caltech has demonstrated that in quantum communication, the goal is to use entangled atoms as qubits to share, or teleport, quantum information, and they have built a platform that can handle multiple channels at once. Their Feb report on multiplexing entanglement in a quantum network shows how careful control of atomic states and optical modes can turn a single physical link into many logical ones, a prerequisite for any practical quantum internet.

Multiplexed crystals and many-qubit nodes

Another Caltech led effort has pushed this multiplexing idea into solid state crystals that can host many qubits in a compact volume. Working with a yttrium orthovanadate platform, the team has shown that the crystal can accommodate a large number of atomic qubits, with each node in their demonstration containing approximately 20. As they describe it, the But crucial feature is that each of these qubits can be individually addressed and entangled through shared optical modes, turning the crystal into a dense hub for quantum networking.

Embedding so many qubits in a single material raises new challenges in cross talk and decoherence, but it also opens the door to error correction and more complex protocols within each node. I see this as a bridge between the small, few qubit demonstrations that dominated early quantum optics and the larger scale architectures needed for real world applications. If a single crystal can reliably host tens of entangled qubits, then linking a modest number of such nodes could already outperform classical communication schemes in specific tasks like secure key distribution.

Bridging macro and micro in quantum optics

One recurring theme in nanoscale entanglement research is the effort to connect tabletop optical setups with chip scale devices. P. James Schuck, Columbia Engineering, a professor at Columbia Engineering, has argued that recent work on quantum entanglement at the nanoscale connects large scale and small scale quantum optics, potentially enabling quantum communication that fits into something as familiar as a mobile phone. By integrating emitters, cavities and waveguides into a single nanostructured platform, his community is trying to shrink the bulky components of quantum optics labs into devices that could be manufactured and deployed widely.

Another perspective on this bridge comes from a separate analysis that described a new nanoscale entanglement device as the embodiment of the long sought goal of linking macroscopic and microscopic nonlinear and quantum optical phenomena. In that report, the authors emphasized how their structure allowed strong nonlinear interactions at the level of single photons while still being compatible with conventional optical systems. The Jan description of this work underscores how far the field has come from isolated quantum dots or ions toward integrated platforms that can plug into existing fiber networks and detectors.

Decoherence: the nanoscale nemesis

All of these advances are constrained by the same fundamental problem, which is that entangled states are extremely fragile and susceptible to decoherence. Any interaction with stray electromagnetic fields, nearby defects or thermal vibrations can disrupt the entanglement and render the whole thing useless long before it reaches a detector. A clear explanation of this challenge notes that Entangled states are extremely fragile and susceptible to decoherence, and that even tiny perturbations can collapse the quantum correlations that devices are trying to preserve.

At the nanoscale, surfaces and interfaces play an outsized role in this process because a large fraction of the qubit’s environment is defined by nearby atoms and defects. Another analysis from Caltech points out that the problem is that entangled particles become entangled with the environment around them quickly, in a matter of microseconds, which can render a carefully prepared state useless for computation or communication. The Oct discussion of untangling entanglement emphasizes that controlling this unwanted coupling is just as important as generating the desired correlations in the first place.

Cryogenics and environmental control

To fight decoherence, many nanoscale entanglement experiments operate at temperatures close to absolute zero, where thermal vibrations are dramatically suppressed. Even a seemingly small temperature differential can have monumentally significant ramifications for quantum technology, because a slight increase in thermal energy can kick qubits out of their delicate superpositions and into classical states. One technical overview stresses that Even modest warming can drive quantum states into classical binary states through decoherence, which is why dilution refrigerators and cryogenic wiring have become standard infrastructure in quantum labs.

Environmental control goes beyond temperature, extending to electromagnetic shielding, vibration isolation and careful filtering of control signals. At the nanoscale, this often means co designing the device and its packaging so that unwanted modes are damped while useful ones are preserved. I see a growing recognition that cryogenics and materials engineering are as central to building entangled systems as the quantum algorithms they will eventually run, because without a quiet enough environment, no amount of clever protocol design can keep entanglement alive.

Where nanoscale entanglement is heading

Looking across these efforts, a coherent picture emerges of entanglement as a practical engineering target rather than a purely theoretical curiosity. Researchers are learning to generate entangled photons in van der Waals crystals, to entangle phonons in mechanical resonators, and to pack dozens of atomic qubits into multiplexed crystals that act as network nodes. At the same time, they are mapping out the limits imposed by decoherence and building the cryogenic and nanofabrication infrastructure needed to push those limits back.

If these trends continue, I expect nanoscale entanglement to move steadily from bespoke laboratory setups into more standardized platforms, much as transistors evolved from hand wired prototypes into mass produced chips. The fact that experiments now hint at quantum communication compatible with mobile phone form factors, and that quantum sound devices are being framed as unit cells of future processors, suggests that the building blocks are already taking shape. The remaining work lies in stitching them together into systems that can operate reliably outside the lab while still respecting the unforgiving rules of the quantum world.

More from Morning Overview